Future historians may register it as the day when usually unflappable Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov decided he had had enough:

“We are getting used to the fact that the European Union are trying to impose unilateral restrictions, illegitimate restrictions and we proceed from the assumption at this stage that the European Union is an unreliable partner.”

Josep Borrell, the EU foreign policy chief, on an official visit to Moscow, had to take it on the chin.

Lavrov, always the perfect gentleman, added, “I hope that the strategic review that will take place soon will focus on the key interests of the European Union and that these talks will help to make our contacts more constructive.”

He was referring to the EU heads of state and government’s summit at the European Council next month, where they will discuss Russia. Lavrov harbors no illusions the “unreliable partners” will behave like adults.

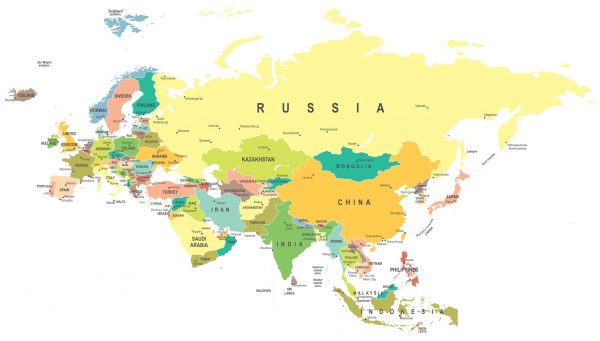

Yet something immensely intriguing can be found in Lavrov’s opening remarks in his meeting with Borrell: “The main problem we all face is the lack of normalcy in relations between Russia and the European Union – the two largest players in the Eurasian space. It is an unhealthy situation, which does not benefit anyone.”

The two largest players in the Eurasian space (italics mine). Let that sink in. We’ll be back to it in a moment.

As it stands, the EU seems irretrievably addicted to worsening the “unhealthy situation”. European Commission head Ursula von der Leyen memorably botched the Brussels vaccine game.

Essentially, she sent Borrell to Moscow to ask for licensing rights for European firms to produce the Sputnik V vaccine – which will soon be approved by the EU.

And yet Eurocrats prefer to dabble in hysteria, promoting the antics of NATO asset and convicted fraudster Navalny – the Russian Guaido.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, under the cover of “strategic deterrence”, the head of the US STRATCOM, Admiral Charles Richard, casually let it slip that “there is a real possibility that a regional crisis with Russia or China could escalate quickly to a conflict involving nuclear weapons, if they perceived a conventional loss would threaten the regime or state.”

So the blame for the next – and final – war is already apportioned to the “destabilizing” behavior of Russia and China. It’s assumed they will be “losing” – and then, in a fit of rage, will go nuclear.

The Pentagon will be no more than a victim; after all, claims Mr. STRATCOM, we are not “stuck in the Cold War”.

STRATCOM planners could do worse than read crack military analyst Andrei Martyanov, who for years has been on the forefront detailing how the new hypersonic paradigm – and not nuclear weapons – has changed the nature of warfare.

After a detailed technical discussion, Martyanov shows how “the United States simply has no good options currently. None.

The less bad option, however, is to talk to Russians and not in terms of geopolitical BS and wet dreams that the United States, somehow, can convince Russia “to abandon” China – US has nothing, zero, to offer Russia to do so.

But at least Russians and Americans may finally settle peacefully this “hegemony” BS between themselves and then convince China to finally sit as a Big Three at the table and finally decide how to run the world. This is the only chance for the US to stay relevant in the new world.”

The Golden Horde imprint

As much as the chances are negligible of the EU getting a grip on the “unhealthy situation” with Russia, there’s no evidence what Martyanov outlined will be contemplated by the US Deep State.

The path ahead seems ineluctable: perpetual sanctions; perpetual NATO expansion alongside Russia’s borders; the build up of a ring of hostile states around Russia; perpetual US interference on Russian internal affairs – complete with an army of fifth columnists; perpetual, full spectrum information war.

Lavrov is increasingly making it crystal clear that Moscow expects nothing else. Facts on the ground, though, will keep accumulating.

Nordstream 2 will be finished – sanctions or no sanctions – and will supply much needed natural gas to Germany and the EU. Convicted fraudster Navalny – 1% of real “popularity” in Russia – will remain in jail. Citizens across the EU will get Sputnik V.

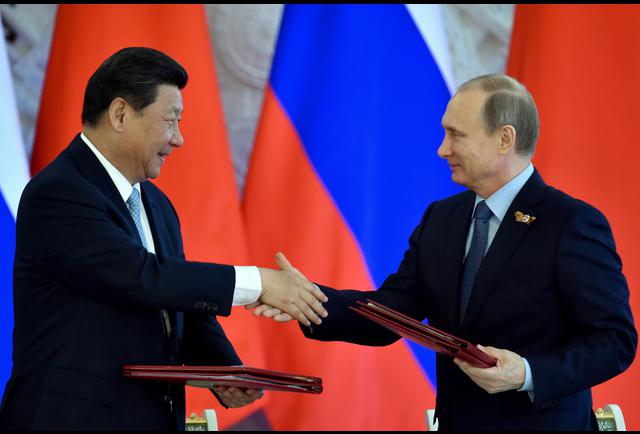

The Russia-China strategic partnership will continue to solidify.

To understand how we have come to this unholy Russophobic mess, an essential road map is provided by Russian Conservatism, an exciting, new political philosophy study by Glenn Diesen, associate professor at University of Southeastern Norway, lecturer at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, and one of my distinguished interlocutors in Moscow.

Diesen starts focusing on the essentials: geography, topography and history. Russia is a vast land power without enough access to the seas.

Geography, he argues, conditions the foundations of “conservative policies defined by autocracy, an ambiguous and complex concept of nationalism, and the enduring role of the Orthodox Church” – something that implies resistance to “radical secularism”.

It’s always crucial to remember that Russia has no natural defensible borders; it has been invaded or occupied by Swedes, Poles, Lithuanians, the Mongol Golden Horde, Crimean Tatars and Napoleon. Not to mention the immensely bloody Nazi invasion.

What’s in a word? Everything: “security”, in Russian, is byezopasnost. That happens to be a negative, as byez means “without” and opasnost means “danger”.

Russia’s complex, unique historical make-up always presented serious problems. Yes, there was close affinity with the Byzantine empire. But if Russia “claimed transfer of imperial authority from Constantinople it would be forced to conquer it.” And to claim the successor, role and heritage of the Golden Horde would relegate Russia to the status of an Asiatic power only.

On the Russian path to modernization, the Mongol invasion provoked not only a geographical schism, but left its imprint on politics: “Autocracy became a necessity following the Mongol legacy and the establishment of Russia as an Eurasian empire with a vast and poorly connected geographical expanse”.

“A colossal East West”

Russia is all about East meets West. Diesen reminds us how Nikolai Berdyaev, one of the leading 20th century conservatives, already nailed it in 1947: “The inconsistency and complexity of the Russian soul may be due to the fact that in Russia two streams of world history – East and West – jostle and influence one another (…) Russia is a complete section of the world – a colossal East West.”

The Trans-Siberian railroad, built to solidify the internal cohesion of the Russian empire and to project power in Asia, was a major game-changer: “With Russian agricultural settlements expanding to the east, Russia was increasingly replacing the ancient roads who had previously controlled and connected Eurasia.”

It’s fascinating to watch how the development of Russian economics ended up on Mackinder’s Heartland theory – according to which control of the world required control of the Eurasian supercontinent.

What terrified Mackinder is that Russian railways connecting Eurasia would undermine the whole power structure of Britain as a maritime empire.

Diesen also shows how Eurasianism – emerging in the 1920s among émigrés in response to 1917 – was in fact an evolution of Russian conservatism.

Eurasianism, for a number of reasons, never became a unified political movement. The core of Eurasianism is the notion that Russia was not a mere Eastern European state.

After the 13th century Mongol invasion and the 16th century conquest of Tatar kingdoms, Russia’s history and geography could not be only European. The future would require a more balanced approach – and engagement with Asia.

Dostoyevsky had brilliantly framed it ahead of anyone, in 1881:

“Russians are as much Asiatics as European. The mistake of our policy for the past two centuries has been to make the people of Europe believe that we are true Europeans. We have served Europe too well, we have taken too great a part in her domestic quarrels (…) We have bowed ourselves like slaves before the Europeans and have only gained their hatred and contempt. It is time to turn away from ungrateful Europe. Our future is in Asia.”

Lev Gumilev was arguably the superstar among a new generation of Eurasianists. He argued that Russia had been founded on a natural coalition between Slavs, Mongols and Turks.

The Ancient Rus and the Great Steppe, published in 1989, had an immense impact in Russia after the fall of the USSR – as I learned first hand from my Russian hosts when I arrived in Moscow via the Trans-Siberian in the winter of 1992.

As Diesen frames it, Gumilev was offering a sort of third way, beyond European nationalism and utopian internationalism. A Lev Gumilev University has been established in Kazakhstan. Putin has referred to Gumilev as “the great Eurasian of our time”.

Diesen reminds us that even George Kennan, in 1994, recognized the conservative struggle for “this tragically injured and spiritually diminished country”. Putin, in 2005, was way sharper. He stressed,

“the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century. And for the Russian people, it was a real drama (…) The old ideals were destroyed. Many institutions were disbanded or simply hastily reformed…With unrestricted control over information flows, groups of oligarchs served exclusively their own corporate interests. Mass poverty started to be accepted as the norm. All this evolved against a background of the most severe economic recession, unstable finances and paralysis in the social sphere.”

Applying “sovereign democracy”

And so we reach the crucial European question.

In the 1990s, led by Atlanticists, Russian foreign policy was focused on Greater Europe, a concept based on Gorbachev’s Common European Home.

And yet post-Cold War Europe, in practice, ended up configured as the non-stop expansion of NATO and the birth – and expansion – of the EU. All sorts of liberal contortionisms were deployed to include all of Europe while excluding Russia.

Diesen has the merit of summarizing the whole process in a single sentence: “The new liberal Europe represented a British-American continuity in terms of the rule of maritime powers, and Mackinder’s objective to organize the German-Russian relationship in a zero-sum format to prevent the alignment of interests”.

No wonder Putin, subsequently, had to be erected as the Supreme Scarecrow, or “the new Hitler”. Putin rejected outright the role for Russia of mere apprentice to Western civilization – and its corollary, (neo) liberal hegemony.

Still, he remained quite accommodating. In 2005, Putin stressed, “above all else Russia was, is and will, of course, be a major European power”. What he wanted was to decouple liberalism from power politics – by rejecting the fundamentals of liberal hegemony.

Putin was saying there’s no single democratic model. That was eventually conceptualized as “sovereign democracy”. Democracy cannot exist without sovereignty; so that discards Western “supervision” to make it work.

Diesen sharply observes that if the USSR was a “radical, left-wing Eurasianism, some of its Eurasian characteristics could be transferred to conservative Eurasianism.”

Diesen notes how Sergey Karaganov, sometimes referred to as the “Russian Kissinger”, has shown “that the Soviet Union was central to decolonization and it mid-wifed the rise of Asia by depriving the West of the ability to impose its will on the world through military force, which the West had done from the 16th century until the 1940s”.

This is largely acknowledged across vast stretches of the Global South – from Latin America and Africa to Southeast Asia.

Eurasia’s western peninsula

So after the end of the Cold War and the failure of Greater Europe, Moscow’s pivot to Asia to build Greater Eurasia could not but have an air of historical inevitability.

The logic is impeccable. The two geoeconomic hubs of Eurasia are Europe and East Asia. Moscow wants to connect them economically into a supercontinent: that’s where Greater Eurasia joins China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

But then there’s the extra Russian dimension, as Diesen notes: the “transition away from the usual periphery of these centers of power and towards the center of a new regional construct”.

From a conservative perspective, emphasizes Diesen, “the political economy of Greater Eurasia enables Russia to overcome its historical obsession with the West and establish an organic Russian path to modernization”.

That implies the development of strategic industries; connectivity corridors; financial instruments; infrastructure projects to connect European Russia with Siberia and Pacific Russia. All that under a new concept: an industrialized, conservative political economy.

The Russia-China strategic partnership happens to be active in all these three geoeconomic sectors: strategic industries/techno platforms, connectivity corridors and financial instruments.

That propels the discussion, once again, to the supreme categorical imperative: the confrontation between the Heartland and a maritime power.

The three great Eurasian powers, historically, were the Scythians, the Huns and the Mongols. The key reason for their fragmentation and decadence is that they were not able to reach – and control – Eurasia’s maritime borders.

The fourth great Eurasian power was the Russian empire – and its successor, the USSR. A key reason the USSR collapsed is because, once gain, it was not able to reach – and control – Eurasia’s maritime borders.

The US prevented it by applying a composite of Mackinder, Mahan and Spykman. The US strategy even became known as the Spykman-Kennan containment mechanism – all these “forward deployments” in the maritime periphery of Eurasia, in Western Europe, East Asia and the Middle East.

We all know by now how the overall US offshore strategy – as well as the primary reason for the US to enter both WWI and WWII – was to prevent the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon by all means necessary.

As for the US as hegemon, that would be crudely conceptualized – with requisite imperial arrogance – by Dr. Zbig “Grand Chessboard” Brzezinski in 1997: “To prevent collusion and maintain security dependence among the vassals, to keep tributaries pliant and protected, and keep the barbarians from coming together”.

Good old Divide and Rule, applied via “system-dominance”.

It’s this system that is now tumbling down – much to the despair of the usual suspects. Diesen notes how, “in the past, pushing Russia into Asia would relegate Russia to economic obscurity and eliminate its status as a European power.”

But now, with the center of geoeconomic gravity shifting to China and East Asia, it’s a whole new ball game.

The 24/7 US demonization of Russia-China, coupled with the “unhealthy situation” mentality of the EU minions, only helps to drive Russia closer and closer to China exactly at the juncture where the West’s two centuries-only world dominance, as Andre Gunder Frank conclusively proved, is coming to an end.

Diesen, perhaps too diplomatically, expects that “relations between Russia and the West will also ultimately change with the rise of Eurasia. The West’s hostile strategy to Russia is conditioned on the idea that Russia has nowhere else to go, and must accept whatever the West offers in terms of “partnership”.

The rise of the East fundamentally alters Moscow’s relationship with the West by enabling Russia to diversify its partnerships”.

We may be fast approaching the point where Great Eurasia’s Russia will present Germany with a take it or leave it offer.

Either we build the Heartland together, or we will build it with China – and you will be just a historical bystander. Of course there’s always the inter-galaxy distant possibility of a Berlin-Moscow-Beijing axis. Stranger things have happened.

Meanwhile, Diesen is confident that “the Eurasian land powers will eventually incorporate Europe and other states on the inner periphery of Eurasia.

Political loyalties will incrementally shift as economic interests turn to the East, and Europe is gradually becoming the western peninsula of Greater Eurasia”.

Talk about food for thought for the peninsular peddlers of the “unhealthy situation”.

***

By Pepe Escobar

Published by Asia Times

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.