Shooting deaths of nine African Americans represents a legacy of racial violence and exploitation

Note: Delivered as a keynote address, this presentation was a major part of a Workers World Party Detroit Branch public meeting held on Sat. July 18, 2015. The event was chaired by Chae Davis of Fight Imperialism, Stand Together (FIST). A report on the relationship between the struggle of the LGBTQ Community and Black Lives Matter was addressed by Martha Grevatt, a labor historian, autoworker and activist who also is a member of the Moratorium NOW! Coalition in Detroit.

This meeting is being held in tribute to the nine martyrs killed in Charleston, South Carolina on June 17 as well as the millions of other ancestors that laid down their lives for the freedom of African people and the total liberation of humanity. Let us have a brief moment of silence and reflection on those who were massacred simply because their skin was black.

We are continuing today our consistent process of political education related to the need to build a revolutionary organization of the workers and the oppressed. In this organizing center we do take political education seriously.

In fact we are not hesitant at all to say that without research, study and analysis utilizing the scientific methodology of dialectical and historical materialism, that a genuine revolutionary movement cannot emerge with the capacity of challenging and defeating international finance capital; i.e., world capitalism and imperialism. It is our application of research, study and analysis that our strategies and tactics develop.

Testing our theoretical and ideological assumptions in the real world strengthens our capacity to continue the struggle. Recognizing that things are constantly changing even if they appear not to, requires that we adapt our tactics to the shifting situation.

Eleven years ago during the U.S. occupation of Iraq we created the Annual Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Rally and March. The event resurrects the actual legacy of Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement by emphasizing the struggle against war, poverty, racism and for social justice and self-determination. Through this event we are able to bring together hundreds of the best activists and organizations throughout the region of Southeast Michigan and beyond.

During the period leading up to the illegal imposition of emergency management and bankruptcy, we through the Moratorium NOW! Coalition in alliance with others, turned the discussion towards the role of the banks and corporations which are at the root of the economic crisis not only in Michigan but throughout the country and internationally. Our correctness on this position is reflected in the present situation in Greece, a European country which is credited by many historians as the cradle of what has become known as Western civilization.

The plight of the workers in Greece is analogous to the status of the people of Detroit and the state of Michigan. Just this week we joined a nationwide effort to express solidarity with the people of Greece outside Chase Bank downtown.

These are only a few examples of how we apply our political education process to the concrete conditions in existence today. We clearly recognize that in order for the system to be transformed it will take a mass movement guided by scientific thought and organization.

Recent Developments in the Anti-Racist Movement in the United States

On June 17 a massacre of nine African Americans at the Mother Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Charleston, South Carolina sent shock waves throughout the U.S. and the world. This racist killing inside an historic church founded in the resistance to slavery in 1818, was by no means an isolated incident.

Over the last year we have witnessed what can only be considered as an upsurge in exposure and response to the blatant murder and torture of African Americans in the U.S. In Ferguson, Missouri, the police killing of Michael Brown set off months of demonstrations and rebellions that were not anticipated by the ruling class or the anti-racist movement.

Ferguson is a small suburb outside St. Louis with a majority super-exploited and oppressed community. Not only are people subjected to the threat of brutality by the police but they are railroaded through the courts and forced to pay unnecessary and unwarranted fines as motorists.

A study conducted by the New York Times last fall revealed that for all practical purposes every household in Ferguson had someone or several people who had outstanding warrants, much of which involves the racial profiling of African American motorists. In an effort to calm the social situation in Ferguson and St. Louis County, the courts sought to grant some form of an amnesty for residents where they could come forward and pay lesser amounts in fines in order to have the pending arrest warrants lifted.

Even the Department of Justice (DOJ) report stemming from their investigation in St. Louis County after the killing of Brown revealed that various branches of government in effect collude to deliberately target African Americans for traffic stops and ticketing. There were e-mails cited in the DOJ report illustrating how the various branches of law-enforcement in conjunction with municipal bureaucracies set goals for funding based upon traffic stops where sometimes up to four tickets were written on a single vehicle.

A subsequent report by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) noted that the entire St. Louis County municipal structures were inherently inefficient and irrational. There are numerous suburbs which have semi-autonomous governing units which are all seeking to maintain their existence. The exploitation of African American motorists and pedestrians through aggressive policing is a source for revenue generation and social containment.

Despite these conspiratorial crimes being committed under the cloak of legality, the DOJ refused to indict anyone including white police officer Darren Wilson who shot dead an unarmed Michael Brown. Several officials in law-enforcement and the courts resigned in what appeared to be a deal worked out between the federal government and the local authorities.

A similar situation took place in Cleveland, Ohio in the aftermath of the blatant police killing of 12-year-old Tamir Rice who was gunned down in a public park for playing with a toy gun. Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder went to Cleveland after the slaying of Rice announcing that a federal consent decree would be imposed without providing any guidance on how such an agreement with the authorities could stop police brutality and murder.

Those of us who follow police misconduct throughout various cities across the U.S. know that there have been scores of consent decrees enacted yet law-enforcement violence against the people continues. This is due to the fact that the police represent the racist capitalist state. Their principal task is to defend private property and the status quo of class and national oppression. Until capitalism is removed from the U.S. police brutality cannot be eliminated no matter how many half-measures are taken in response to exposures of the crimes committed by the cops or when the people reach a boiling point and urban rebellion occurs.

In Baltimore, where another rebellion erupted in late April, the situation resembles what is taking place in Detroit. Large swaths of the city have been devastated by the international banks through predatory lending and evictions.

Other methods of forced removal are also taking place around John Hopkins University and the downtown area as well as on the docks. Under the guise of urban redevelopment, the African American and working class communities are put under enormous pressure.

What is usually left for the oppressed is to carve out an existence through low-wage employment or the informal sector of the economy. A small stratum of politicians, police and civil servants serve as a buffer between the moneyed interest downtown that is tied to the financial institutions and multi-national corporations.

Another similarity with Detroit is the attack on water services. Some 25,000 households have been slated for water shut-offs in Baltimore. Here in Detroit it is the widespread termination of services over the last year as well as the regionalization of the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) as a precursor for privatization.

Therefore, when we examine the conditions under which African Americans live in Ferguson and Baltimore it is not done in the abstract. Such an analysis is carried out in an effort to gain clearer insight into the struggle in Detroit which we are waging every day.

Moreover, this struggle is not a new one. The revolts against slavery and national oppression began on the continent of Africa and extended into the Western hemisphere including the British colonies and the U.S. after 1776.

The Character of Slavery and Resistance in South Carolina

Africans in America have been fighting racism and genocidal violence since 1619 when 20 people were brought to Jamestown, Virginia, a British colony, for the purpose of indentured servitude. Within 40 years Africans as a whole were confined to slave status in the colonies and the later United States of America.

According to the South Carolina Information Highway in regard to the development of the Atlantic Slave Trade with specific reference to the Carolinas:

“Slavery was well established in the “New World” by the Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch, who all sent African slaves to work in both North and South America during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The English began aggressively trading in what was called “black ivory” during the middle of the seventeenth century, spurred on by the need for laborers in the hot, humid sugar fields on the West Indian islands of Barbados, St. Christopher, the Bermudas, and Jamaica. By the time Charles Towne was settled in 1670, Englishmen from the West Indies were well acquainted with slavery and the huge profits they could reap from the toil of others. Slavery was therefore considered an essential ingredient in the successful establishment of cash crop plantations in South Carolina.”

This same article goes on to say “Like other European nations, England created the Royal African Company to underwrite the slave trade. A string of forts and “slave factories” were established from the Cape Verde Islands to the Bight of Biafra. But the slave trade would likely not have been as ‘successful’ were it not for the ‘unholy alliance’ between the English (and other European nations) and the African kingdoms on whose territories the forts stood. The English slave traders did their best to dupe the native kings…. For their cargoes of human flesh, the traders brought iron and copper bars, brass pans and kettles, cowry shells, old guns, gun powder, cloth, and alcohol.

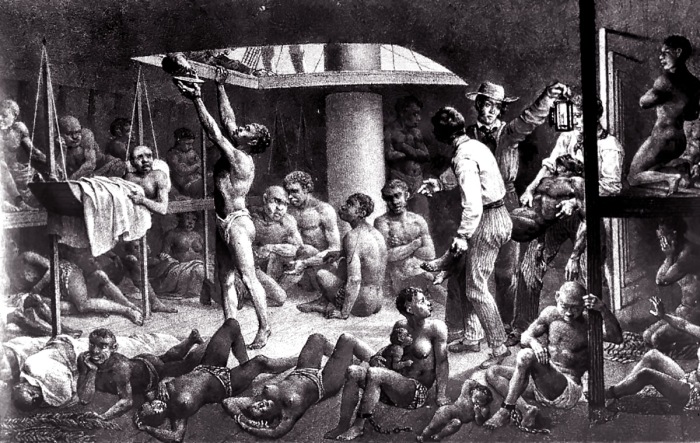

In return, ships might load on anywhere from 200 to over 600 African slaves, stacking them like cord wood and allowing almost no breathing room. The crowding was so severe, the ventilation so bad, and the food so poor during the ‘Middle Passage’ of between five weeks and three months that a loss of around 14 to 20% of their ‘cargo’ was considered the normal price of doing business. This slave trade is thought to have transported at least 10 million and perhaps as many as 20 million, Africans to the American shore.”

South Carolina became one of the most prosperous slave colonies and later states. The production of rice and other agricultural commodities necessitated a large reservoir of enslaved Africans. By the conclusion of the 18th century Africans outnumbered whites in the state. This situation continued for decades requiring a highly repressive and brutal system of exploitation and social control.

The introduction of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793 increased the demand for production. A burgeoning market for textiles in Northern states and in England fueled the growth of cotton production and consequently slave labor.

Such intense production of agricultural products depleted the soil as well. This necessitated the expansion of the slave system further west. Eventually the interests of the Northern industrialists and the Southern planters came into conflict leading to strained relations and the eventual Civil War. The capitalist mode of production was fostered by the profits accrued from the exploitation of African labor with spawning of new industries such as banking, shipping and eventually steam technology.

Moreover, by 1860 South Carolina had more slave owners per 1000 people than any other state. The intensity of slave ownership in South Carolina meant a sharp increase in enslaved Africans. South Carolina’s population imbalance between enslaved Africans and whites, even poor ones, prompted a repressive and highly exploitative system.

Resistance to Slavery

From the struggles of Africans on the West coast of the continent to Telemaque, also known as Denmark Vesey, who was a co-founder of Mother Emmanuel Church, slavery and racist violence has been challenged.

Looking at the history that is taught in the public schools, one would never know that Africans resisted enslavement. Slave revolts became more frequent during the early decades of the 19th century.

During African American History Month in February, we published an article on the often hidden and forgotten slave revolt in New Orleans during 1811. This revolt was led by two Africans whose immediate ancestry was in the area now known as Ghana in West Africa.

The Africans who led the revolt were well aware of the Haitian Revolution as well as the struggles between Spain and the U.S. over control of the western hemisphere. The objective of the Africans who revolted was to take control of an arms depot in New Orleans, distribute guns and in order to seize the plantations and declare their independence from the slave system.

This rebellion did not reach its objectives but it so traumatized the white slavocracy that they effectively wrote it out of history. Such developments defy the notions of the inherent inferiority of African people, a myth that was created to justify slavery and its brutal character.

With specific reference to the Denmark Vesey Revolt plot, it is important to emphasize that it grew out of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) which was founded through the Free African Society of Philadelphia during the 1780s and 1790s. Key figures in the origins of the Society and later Church were Richard Allen, Sara Allen and Abasalom Jones.

The Emanuel AME Church was one of the earliest in the South. Denmark Vesey was a co-founder of the Church.

Vesey was born in the Danish colony of St. Thomas in 1767 which was later sold to the U.S. during the early years of the 20th century. He was later brought to South Carolina as a slave after spending time in Haiti. He won his freedom, became literate and a skilled tradesman.

The scheduled rebellion in 1822 led by Vesey was to take place on July 14, Bastille Day, confirming the awareness of these Africans in regard to international affairs and the role of bourgeois revolutions during the period. The date was moved up to June 16 since there were fears that the plot had gotten out to the slave masters. When the plot was revealed Vesey and dozens of others were hung after a brief secret trial.

Other Africans were exiled from South Carolina back to the Caribbean and other states. The Emanuel AME Church was burned to the ground by the slave masters. The Church was later completely outlawed forcing its adherents to meet underground for decades. They were not able to operate in the open until after the conclusion of the Civil War.

The Denmark Vesey plot was followed some nine years later by the uprising in South Hampton County, Virginia led by Nat Turner. This revolt succeeded in exacting retribution on some slave owners in the area. Turner was eventually captured and executed.

However, the Nat Turner revolt shook up the white slave system. It served to create the political atmosphere for the growth of the abolitionist movement. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was more of an act of desperation for system that was already in deep crisis by the beginning of the middle of the 19th century.

By 1856, during the lead up to the national elections, there were reports of slave rebellions and plots throughout the South. John Brown and his cohorts launched their campaign in Kansas. Later in 1859 the first skirmishes of the Civil War began at Harper’s Ferry where John Brown, Osborne Anderson and others sought to spark an insurrection with the seizure of the area.

Brown was hung after being captured. Nonetheless, Anderson was able to escape and wrote one of the most compelling accounts of an insurrection against slavery during the period.

By April 1861, the confederate soldiers at Fort Sumter, South Caroline refused to take orders from President Abraham Lincoln after a decision by the slavocracy to succeed from the Union. These events represented the beginning of the Civil War, a violent conflict which led to the abolition of legalized slavery and the beginning of Reconstruction in the late 1860s.

Reconstruction and Civil Rights in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Bishop Henry McNeal Turner and Septima Poinsette Clark of the 19th and 20th centuries are just two historical figures who represent a legacy of resistance and revolutionary struggle. Here again these heroic fighters are often written out of the historical accounts of the post slavery and civil rights eras.

Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois some 80 years ago in 1935, wrote “Black Reconstruction in America,” a pioneering study subtitled “An Essay Toward a History of the Past Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-80.” In essence this was the first serious social scientific study done on the period after the Civil War and the eventual defeat of federal Reconstruction.

Du Bois spent two decades working on this study. It was largely ignored within the white dominated academic community and denounced for being biased in favor of African Americans and their role in the attempt to build a genuine democratic system inside the U.S. Some of the most progressive legislation came out of this period dealing with public education, access to land and state resources.

Nonetheless, Reconstruction was defeated on a federal level after the national elections of 1876. It continued however, against all odds in state governmental structures through the 1880s and in some areas until the early years of the 20th century.

Du Bois noted in Black Reconstruction in the chapter entitled “The Black Proletariat in South Carolina”, that “in a state where blacks outnumbered whites, the will of the mass of black labor, modified by their own and other leaders and dimmed by ignorance, inexperience and uncertainty, dictated the form and methods of government.”

He then went on to record that “A great political scientist in one of the oldest and largest of American universities wrote and taught thousands of youth and readers that ‘There is no question now, that Congress did a monstrous thing, and committed a great political error, if not a sin, in the creation of this new electorate. It was a great wrong to civilization to put the white race of the South under the domination of the Negro race. The claim that there is nothing in the color of the skin from the point of view of political ethics is a great sophism. A black skin means membership in a race of men which has never of itself succeeded in subjecting passion to reason; he has never, therefore, created any civilization of any kind.”

Of course this was not the view of many European explorers and historians for thousands of years dating back to the ancient Greeks who credited Africans with the genesis of their thinking on philosophy and science. This as well does not account for the repressive measures initiated against Africans during slavery and afterwards designed to suppress their right to self-determination and full equality. (See Herodotus, An Account of Egypt, 5th Century B.C.)

If the European-American civilization was based on higher values than encompassed by Africans and their social culture, then how does one account for the blatant disrespect of the collective and individual rights of the enslaved along with those released from bondage. Therefore, in order to save the oppressed from their own destruction the ruling class must exercise extreme forms of exploitation and repression. Such a line of thinking is irrational and does not speak to the actual history of the period of slavery as well as Reconstruction.

Du Bois writes of the situation in South Carolina immediately after the Civil War saying at the aegis of Andrew Johnson, the successor to the slain Abraham Lincoln that “The legislature which met after this election passed one of the most vicious of the Black Codes. It provides for corporal punishment, vagrancy and apprenticeship laws, openly made the Negro an inferior caste, and provided special laws for his governing.”

Union General William T. Sherman’s Field Order 15 in January 1865 provided hope for a redistribution of land for the emancipated Africans. The Order covered what was known as the “Low Country” from south of Charleston to northern Florida. The plan was ostensibly designed to break up the plantations and to constrain the Southern planters who had been the basis for the succession.

Georgia Encyclopedia says of this period “Sherman’s radical plan for land redistribution in the South was actually a practical response to several issues. Although Sherman had never been a racial egalitarian, his land-redistribution order served the military purpose of punishing Confederate planters along the rice coast of the South for their role in starting the Civil War, while simultaneously solving what he and Radical Republicans viewed as a major new American problem: what to do with a new class of free Southern laborers. Congressional leaders convinced President Lincoln to establish the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands on March 3, 1865, shortly after Sherman issued his order. The Freedmen’s Bureau, as it came to be called, was authorized to give legal title for forty-acre plots of land to freedmen and white Southern Unionists.” (georgiaencyclopedia.org)

This same article continues saying “The immediate effect of Sherman’s order provided for the settlement of roughly 40,000 blacks (both refugees and local slaves who had been under Union army administration in the Sea Islands since 1861). This lifted the burden of supporting the freedpeople from Sherman’s army as it turned north into South Carolina. But the order was a short-lived promise for blacks. Despite the objections of General Oliver O. Howard, the Freedmen’s Bureau chief, U.S. President Andrew Johnson overturned Sherman’s directive in the fall of 1865, after the war had ended, and returned the land along the South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida coasts to the planters who had originally owned it.”

Despite these efforts aimed at sabotaging Reconstruction, African Americans through their own initiatives played a decisive role in challenging the system of institutional racism. One such person who was born in South Carolina was AME Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (1834-1915).

Turner was a free African born in Newberry Courthouse, South Carolina to Sarah Greer and Hardy Turner. Despite the obstacles placed upon Africans gaining a formal education, Turner was able to receive training. He would work in a law firm first as a janitor and later was able to master the English language and writing.

He converted to the Methodist church and became a preacher. After becoming ordained in 1853 he traveled extensively throughout the South as an evangelist going as far as New Orleans, Louisiana. Turner married Eliza Peacher and they had fourteen children only four of whom lived to maturity.

Later in 1858, Turner would settle in St. Louis where he was inducted into the AME Church. He would then pastor churches in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. leading into the beginning of the Civil War. While living in Washington, he became associated with abolitionist politicians Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens. By 1863, when Africans were officially incorporated into the Union army he played an important role in the formation of the First Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops and joined the service as an army chaplain for the unit. They were involved in various battles in the theater of war in Virginia.

After the passage of the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, Turner would devote his time to political work. He was a co-founder of the Republican Party in Georgia and served in the state’s constitutional convention before being elected to the Georgia House of Representatives, representing the area around Macon.

Nonetheless, the following year, white legislators voted to expel African Americans from the government saying that former enslaved Africans had no right to serve as public officials. Turner opposed this decision and delivered a powerful speech on the floor of the House. He was later threatened with death by the Ku Klux Klan.

The following year in 1869 he was appointed as the postmaster of Macon by U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant but was soon driven out due to false allegations of criminal and immoral behavior. Later in 1870, with the assistance of the U.S. Congress he was able to reclaim his seat in the Georgia legislature although he was not re-elected to his post as a result of the corrupt practices of local officials.

Turner would later return to work within the AME Church full time and was elected as the 12th Bishop in 1880. By 1885, he became the first bishop to ordain a woman, Sarah Ann Hughes, as a deacon.

Based upon developments inside the U.S. during the 1880s and 1890s when lynching escalated driving African Americans out of political office, skilled jobs and off the land many had acquired in the post-slavery era, Turner became an advocate of emigration to Africa. During the years of 1891 to 1898, he traveled to Africa four times. He extended the influence of the AME Church into Latin America by deploying missionaries to Cuba and Mexico.

He organized two ships where more than 500 Africans were repatriated to Liberia. He also worked with some of the early nationalist leaders from South Africa who would later form the African National Congress (ANC) in 1912. Turner died in Windsor, Ontario Canada in 1915 just across the river from where we are today.

Another often neglected figure in the history of South Carolina was Septima Poinsette Clark who was born in 1898 during the period of reaction after the war on reconstruction. Later in the early decades of the 20th century she qualified as a school educator and joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

As a result of her activism she was barred from teaching in the state of South Carolina. She would later work full time in the Civil Rights Movement as it advanced during the 1940s and 1950s.

She would become a pioneer in the field of Civil Rights education where she trained thousands in voter registration and political involvement. Clark served as the first woman board member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) founded by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Clark made her contributions within SCLC despite the atmosphere of male domination and patriarchal attitudes. It would take decades for her to win recognition for her contributions.

This writer published an article in June reviewing the contributions of Clark saying “A pioneer in mass education, Clark’s work linked adult literacy to the struggle for Civil Rights and political representation. Political education is needed desperately in 2015 as African Americans renew the struggle against racism and for self-determination along with full equality.”

In this same report it stresses that “Since the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the ruling class has waged a campaign to reverse all the gains won during the period between the 1940s and 1970s. Today the Voting Rights Act of 1965 has been stripped of its enforcement provisions while in many states affirmative action programs designed to re-correct historic disparities in education, housing, employment and women rights have been eviscerated. In order to wage these necessary struggles, workers, oppressed people and women must be organized and politically educated. A study and recognition of the lives and contributions of Septima Clark, Ella Baker, Rosa Parks and countless other African American women should be evoked.”

In the Shadow of Racist Violence and National Oppression: Our Task Today

In concluding this presentation we want to go back to where we began. There can be no advancement in the struggle against racism and national oppression absent of revolutionary organization.

We have seen that every major advancement won during the 20th century are in retreat if not having been eviscerated. The system is exposed as being in terminal crisis. There are no other concessions that can be granted without a sustained rebellion or insurrection among the masses of African Americans, Latinos and other oppressed people along with their allies from other communities.

The ultimate objectives of self-determination, national liberation and socio-economic equality and justice cannot be achieved without socialism. That is our mission and we invite all of those here who are motivated by their conscience and burning desire to eliminate injustice to join us in this revolutionary process.

By Abayomi Azikiwe, Editor, Pan-African News Wire