Niger is shaping up to be the surprising frontline of the new Cold War. Yesterday, the 15-member Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) ordered the “activation” and “deployment” of “standby” military forces to the country, an action that threatens to spark a major international war that could make Syria look minor by comparison.

In this venture, ECOWAS has been fully supported by the United States and Europe, leading many to suspect it is being used as an imperial vehicle to stamp out anti-colonial projects in West Africa.

On July 26, a group of Nigerien officers overthrew the corrupt government of Mohamed Bazoum. The move, which the junta presents as a patriotic uprising against a Western puppet, is widely popular in the country, and many of Niger’s neighbors have declared that any attack on it will be considered an attack on all their sovereignty. The United States and France are also considering military action, while many in Niger are calling for Russian aid.

Consequentially, the world waits to see if the region will be engulfed in a war that promises to pull in many of the major global powers.

But what is ECOWAS? And why do so many in Africa consider the organization a tool of Western neocolonialism?

“PART OF A CORRUPT CABAL”

Even before the dust settled in Niger, ECOWAS sprung into action, imposing a no-fly zone and tough economic sanctions, including freezing Nigerien national assets and halting all financial sanctions. Nigeria suspended electricity to its northern neighbor.

The regional bloc also immediately came to the defense of Bazoum, releasing an ominous statement declaring that it would “take all necessary measures,” including “the use of force,” to restore the constitutional order. ECOWAS also gave the new military government a deadline to stand down or face the consequences. That deadline has already passed, and ECOWAS troops are preparing for action.

Member states of ECOWAS may therefore be obliged to send their troops into Niger. Yet many nations are balking at the prospect. Nevertheless, the bloc still seems adamant that military action could come at any time. “We are determined to stop it, but ECOWAS is not going to tell the coup plotters when and where we are going to strike. That is an operational decision that will be taken by the heads of state,” explained Abdel-Fatau Musah, the group’s commissioner for political affairs, peace and security.

Despite not yet acting, the threat of an invasion is far from an idle one. Since 1990, ECOWAS has launched military interventions in seven West African countries, the most recent being in the Gambia in 2017.

This response has disappointed many onlookers. Journalist Eugene Puryear, for example, described the bloc as “part of a corrupt cabal that is directly linked to Western imperial powers to keep Africans poor.”

Those Western powers immediately lined up behind ECOWAS’ position. “The United States welcomes and commends the strong leadership of ECOWAS Heads of State and Government to defend constitutional order in Niger, actions that respect the will of the Nigerien people and align with enshrined ECOWAS and African Union principles of ‘zero tolerance for unconstitutional change,’” read a State Department press release.

Deeming the coup “completely illegitimate,” the French government also said that it “supports with firmness and determination the efforts of ECOWAS to defeat this putsch attempt.” “The EU also associated itself with ECOWAS’ first response to the matter,” said Josep Borrell, the European Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs, thereby greenlighting an intervention.

U.S. Acting Deputy Secretary Victoria Nuland also strongly hinted that the United States is considering invading Niger itself. “It is not our desire to go there, but they [the new military junta] may push us to that point,” Nuland said about her recent trip to Niger, where, she said, she had an “extremely frank and at times quite difficult” meeting with the new leadership.

A measure of how close ECOWAS is to the United States is the constant support Washington gives to the organization. Throughout 2022, the State Department issued statements backing ECOWAS’s position on Mali (another country where the military deposed an unpopular, Western-backed government).

“The United States commends the strong actions taken by ECOWAS in defense of democracy and stability in Mali,” the State Department wrote. It has also issued similar memos reaffirming its unwavering support for ECOWAS’ actions against military coups in Guinea and Burkina Faso. This has led to many critics seeing ECOWAS as little more than a pawn of the United States.

While Washington has presented the situation as ECOWAS defending democracy against authoritarianism, the reality is more complex. Firstly, many of its member states’ governments have decidedly shaky democratic credentials. President Alassane Ouattara of Cote D’Ivoire, for example, violated the country’s term limit law and was controversially sworn in for a third term last year.

Protests against his power grab were suppressed, leaving dozens dead. Meanwhile, Senegalese President Macky Sall’s government has banned the main opposition party and imprisoned its leader.

Furthermore, ECOWAS’ response to coups is far from uniform. After Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba seized power in Burkina Faso in 2022, ECOWAS refused to even impose sanctions, let alone consider an invasion. Instead, they merely asked Damiba to present a timetable for the “reasonable return to constitutional order.” Their indifference to the events may have been due to his staunchly pro-Western outlook and the fact that he had been trained by the U.S. military and the State Department.

ECOWAS’ top leadership is also deeply intertwined with U.S. power. As journalists Alex Rubinstein and Kit Klarenberg noted, the bloc’s chairman, Bola Tinbu, “spent years laundering millions for heroin dealers in Chicago” and later became a key State Department source for analyzing West Africa. Previous ECOWAS chairman Mahamadou Issoufou was also a “staunch ally of the West,” in the words of The Economist” magazine, though many in Africa might use less neutral language to describe him.

In this sense, it might be applicable to compare ECOWAS to other U.S.-dominated regional bodies, such as the Organization of American States (OAS). While the OAS is formally independent, it has constantly aligned itself with Washington and attacked enemy countries like Venezuela and Cuba. A document from USAID (a U.S. governmental organization) noted that the OAS was a crucial tool in “promot[ing] U.S. interests in the Western hemisphere by countering the influence of anti-US countries” like Cuba and Venezuela.

ECONOMIC DOMINATION

ECOWAS traces its own project of African integration back to 1945 and the creation of the CFA franc, a move that brought France’s African colonies into a single currency union. The currency, still in use by 14 African countries today, was artificially pegged to the French franc and later the euro, meaning that importing from and exporting to France (and later the eurozone) was very cheap, but importing from and exporting to the rest of the world was prohibitively expensive.

Therefore, even after formal independence, the CFA franc trapped African countries into economic submission to Paris. As a consequence, many African governments are still powerless to enact serious political and economic changes, seeing as they lack control over their own monetary policy.

This has been a massive boon to France, economically, which enjoys a huge resource base from which to extract raw materials at artificially cheap prices, and also a captive export market. It has also meant that France has maintained a good degree of control over its former colonies. “Without Africa,” former French President François Mitterrand famously said, “France will have no history in the 21st century.”

But this unjust economic system has also benefited African elites, who can import French and European luxuries at the abnormal exchange rate. And it has also allowed them to siphon off African money into European banks, with French authorities happy to turn a blind eye to the practice. France still holds half of the CFA franc countries’ gold reserves.

The result has been stagnation and underdevelopment across francophone Africa. Niger’s real GDP per capita today is significantly lower than what it was at the time of its formal independence from France in 1960. France continues to be by far and away its largest trading partner, with the Nigerien economy revolving around the export of uranium to Paris, where it is used to supply the country with cheap nuclear power.

Yet ordinary Nigeriens see little to no benefit from this arrangement. As Oxfam stated in 2013: “In France, one out of every three light bulbs is lit thanks to Nigerien uranium. In Niger, nearly 90% of the population has no access to electricity. This situation cannot continue.” Thus, to a great extent, France’s prosperity is built upon African suffering, and vice versa.

This explains the widespread anti-colonial sentiment across West Africa. The military coup in July was sparked by public demonstrations against the Bazoum government’s decision to welcome French troops into the country – even after their presence in Mali precipitated a coup last year.

The new Nigerien junta has suspended gold and uranium exports to France. “Down with France, foreign bases out” was the rallying cry of the protestors who took to the streets in the capital, Niamey, and other cities across the country.

Bazoum, however, has remained steadfastly loyal to France. In an interview with “The Financial Times” in May, he defended Paris, claiming that “France is an easy target for the populist discourse of certain opinions, especially on social media among African youth.” Thus, With Bazoum gone, Niger could go from the West’s number one ally in the region to an adversary.

REGIONAL INTEGRATION, REGIONAL WAR?

ECOWAS imposes strict, Western-approved economic measures on its member states, forcing them to obey neoliberal economic laws that make escaping the circle of debt and underdevelopment harder and helped make peaceful, democratic change harder to achieve and, ironically, spurred a flurry of military insurrections across the region.

The coup in Niger follows similar actions in Mali in 2020 and 2021, Burkina Faso (two in 2022) and Guinea (2021). All have positioned themselves as progressive, patriotic, anti-imperialist uprisings against a Western-created economic order. All four nations are currently suspended from ECOWAS.

A host of states have pushed back against the West/ECOWAS’ position. “The authorities of the Republic of Guinea dissociate themselves from the sanctions imposed by ECOWAS,” wrote the Guinean government, describing them as “illegitimate and inhuman” and “urg[ed] ECOWAS to return to better thinking.”

The governments of Mali and Burkina Faso went much further. In a joint communiqué, those nations welcomed Bazoum’s ouster, describing the event as Niger “tak[ing] its destiny into its own hand and to be accountable in the face of history for complete sovereignty.”

Together, they denounced “regional organizations” [i.e., ECOWAS] for imposing sanctions that “increase the populations’ suffering and imperil the spirit of Pan-Africanism.” Perhaps most importantly, however, they bluntly stated that they would come to Niger’s aid militarily if ECOWAS invaded.

“Any military intervention against Niger would mean a declaration of war against Burkina Faso and Mali,” they wrote. Algeria, which shares a long border with Niger, has also warned that it would not stand idle if the West or its puppets attacked Niger.

Pan-Africanism – the anti-imperialist project attempting to create a brotherhood of nations across Africa in order to develop independently – has, of late, experienced a renaissance in Western Africa. Burkina Faso and Mali – Niger’s neighbors to the west – are in advanced stages of merging into a federation.

“The process is underway,” said Ibrahim Traoré, the charismatic military leader of Burkina Faso, revealing that their militaries are now so integrated that “it is really the same army.” He also strongly hinted that he wanted Niger to join the federation:

We cannot exclude the idea that another state with join us…If there are other states that are interested (it’s certain that we will move closer to Guinea) and if others are interested, we need to unite. It’s what the young people are demanding.”

ECOWAS has come out strongly against the idea, but Traoré remained defiant. “We are going to fight, but Africa must unite. The more we are united, the more effective we are,” he said.

Traoré has styled himself as a radical leader in the mold of Thomas Sankara, Burkina Faso’s Marxist revolutionary leader between 1983 and 1987. Sporting a red beret as Sankara did, Traoré asks questions such as “Why does resource-rich Africa remain the poorest region of the world?” and describes many of his fellow African leaders as “puppets in the hands of the imperialists.” He is fond of quoting Cuban leader Che Guevara and has allied his nation with Nicaragua and Venezuela.

COLONIAL OUTPOST

Nigeriens – whether they support the coup or not – are fed up with being treated as a colonial outpost. Bazoum, who came to power in a controversial and disputed 2021 election, saw his approval ratings plummet after it was announced that Niger would host thousands of French troops who had previously been ejected from Mali and Burkina Faso. The presence of those soldiers precipitated coups in both those countries and immediately sparked angry demonstrations in Niger.

Bazoum, who the “BBC” described as a “key Western ally,” failed to read the room and welcomed the troops. Today, Niger hosts almost 1500 French soldiers, as well as many more from the militaries of Germany, Italy and the United States. The new military government has instructed France to remove its troops.

Niger is the cornerstone of the American military operation in Africa, hosting around 1100 personnel across six bases. In 2019, the U.S. opened Air Base 201, a huge $110 million airfield it uses to carry out drone operations across the Sahel region. The stated reason for the foreign troops is to help the region deal with Islamist terrorism.

But the threat of Islamist terrorism only arose from NATO’s 2011 destruction of Libya (another country with which Niger shares a border). The military alliance’s attack turned Libya from a nation with one of the highest standards of living in Africa into a failed state run by Jihadists, replete with open-air slave markets.

The coup, therefore, enjoys widespread support inside the country. A poll published by “The Economist” earlier this week found that 73% of Nigeriens want the military junta to remain in power, with only 27% wishing for Bazoum’s return.

Tens of thousands packed into the Seyni Kountché Stadium in Niamey to express their wish for independence and denounce threats of U.S. or French intervention. “If ECOWAS forces decide to attack our country, before reaching the presidential palace, they will have to walk over our bodies, spill our blood. We will do it [lay down our lives] with pride because we don’t have another country; we only have Niger. Since July 26, our country has decided to take charge of its independence and sovereignty,” said demonstrator Ibrahim Bana.

RUSSIA’S ROLE

While Russia is largely seen in the West as a nefarious, authoritarian regime that interferes in other nations, much of Africa views Moscow in a positive light. The Soviet Union generally supported African independence struggles, and the Russian Federation has not invaded any African nation.

Nearly every African state attended the Russia-Africa Summit in July, while only four African leaders participated in an official meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky last year. The same “Economist” poll asked Nigeriens which foreign power they trusted the most. 60% chose Russia. Only around 1 in 10 chose the U.S., even fewer chose France, and none at all chose Great Britain.

Russian flags are now a common sight in Niamey, with many hoping for some sort of help from Moscow. Ousted President Bazoum, however, took to the pages of “The Washington Post” to ask the U.S. for help, warning that “the entire central Sahel region could fall to Russian influence via the Wagner Group.” Wagner has indeed been invited in by various African governments, including Mali, who see the Russian mercenary force as a counterweight to Western troops. Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin recently spoke approvingly of the coup, although Moscow has been far more reluctant to take sides.

The great worry for many is that the strife in Niger will spark a wider war between West African nations that will no doubt ask for help from Europe and the United States. If this happens, the military governments of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger will doubtless call for Russian aid, turning the situation into something resembling the Syrian Civil War but on a grander scale.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, France shut off energy imports from Russia, making Nigerien uranium for its aging nuclear power plants more crucial. Yet any attempt at regime change in Niger to restart the uranium supply will anger Algeria, with which it recently signed a natural gas importation agreement. Thus, the French position is fraught with contradictions and complications.

As Western power diminishes, a multipolar world is beginning to be born. As part of that birth, the people of Western Africa are dreaming of a different future. Time will tell if the military coups will prove to be a liberatory force or actions that do nothing to help the oppressed people of the region.

One thing is clear, however: the United States and France are unhappy with the changes going on and will fight to maintain their control over Africa. To this end, ECOWAS has proved an important tool at their disposal. Yet with so many conflicting interests and so many forces unwilling to compromise, the situation in Niger threatens to boil over into an international war that will bring global attention to one of the world’s most overlooked regions.

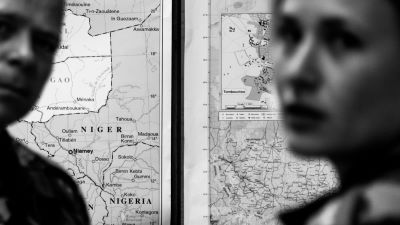

Feature photo | A map of Western Africa provides the backdrop for a brief during Western Accord at Harskamp, the Netherlands, July 24, 2015. Western Accord 2015 is a command post exercise that simulates Western intervention in Mali. Photo | US Army

Alan MacLeod is Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.

Published by Mint Press News

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.com