Armistice Agreement Withdrawal: North Korean Belligerence?

Why has North Korea withdrawn from an armistice agreement that has kept overt hostilities on the Korean peninsula at bay since 1953? Does the withdrawal portend an imminent North Korean aggression? Hardly. North Korea is in no position to launch an attack on its Korean neighbour, or on the United States, at least not one that it would survive.

North Korean forces are dwarfed by the US and South Korean militaries in size, sophistication and fire-power. The withdrawal serves, instead, as a signal of North Korean resolve to defend itself against growing US and South Korean harassment, both military and economic.

US provocations

For decades, North Korea has been subjected to the modern form of the siege. .The aim of the siege is to reduce the enemy to such a state of starvation and deprivation that they open the gate, perhaps killing their leaders in the process and throw themselves on the mercy of the besiegers. [1]

North Korea withstood the siege, and even flourished, during the years it was able to trade with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe’s socialist countries. But with the demise of Soviet socialism, the country has bent, but not broken, under the pressure of US-led sanctions of mass destruction.

Sanctions against North Korea are multi-form, and include a trade blockade and financial isolation. Significantly, no country in history has been menaced by such wide-ranging sanctions for so long. North Korea is, as then US president George W. Bush once remarked, the most sanctioned nation on earth. [2] Sanctions, military harassment (which I.ll come back to in a moment), and the US nuclear threat.

Washington has threatened North Korea with nuclear annihilation on countless occasions. [3] [It has] forced the North Koreans to bulk up militarily, build ballistic missiles, and test nuclear devices in order to survive.

Led by Washington, the UN Security Council has authored a number of resolutions to deny North Korea rights of self-defense and other rights that other countries are free to exercise: The rights to build ballistic missiles; to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty; to launch satellites; to sell arms abroad; and to transfer nuclear technology to other countries.

These are rights that every permanent member of the UN Security Council exercises freely. They are also rights that many other countries enjoy with impunity.

On top of besieging North Korea, Washington and South Korea have for decades kept up a campaign of unrelenting military harassment in the form of regular war games. The latest war games began March 1 and will last for two months.

Undertaken as practice in mobilizing US troops and military hardware from abroad for rapid deployment to the Korean peninsula, the war games this year have activated not only US and South Korean military, but British, Canadian, and Australian forces, as well.

While labelled “defensive,” the war games force the North Koreans onto a permanent war footing. It can never be clear to North Korean generals whether the latest US-South Korean mobilization is a drill or preparation for an invasion. The effect is to force Pyongyang to maintain its military on high alert, an exhausting and expensive exercise.

The view propagated by Western officials and, in train, the Western mass media, is that the sanctions are aimed at correcting North Korea’s bad behavior and that the war games are carried out to deter North Korean aggression. But what’s called “bad behavior,” [i.e.,] “the building of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles” is Pyongyang’s reaction to the US-led permanent state of siege.

A tiny country with a military budget dwarfed by South Korea’s and the United States’ [4] is not credibly an offensive threat to Washington and Seoul, but the United States and South Korea are unquestionably offensive threats to the DPRK (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, North Korea’s official name.)

After the UN maneuvered the Security Council to slap still more sanctions on North Korea, and began its latest round of war games, the Wall Street Journal, revealing its chauvinist leanings, alerted the world that “North Korea [had] moved to further stoke tensions with South Korea.” [5] On the contrary, the United States had further stoked tensions with North Korea.

A dead letter

There are three reasons to regard the armistice agreement as existing in form alone, and not substance.

First, the purpose of the agreement was to set the stage for a permanent peace. Despite North Korea repeatedly asking Washington to enter into a peace agreement, none has been struck. After one North Korean entreaty for peace, then US secretary of state Colin Powell said .”We don’t do non-aggression pacts or treaties, things of that nature.” [6]

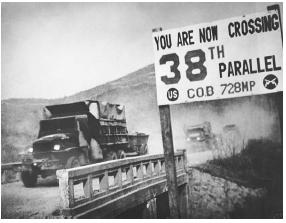

Second, the agreement was to be followed by the withdrawal of all foreign troops from the Korean peninsula. The Chinese withdrew, as did most members of the UN forces. But US forces, which have remained in South Korea for the last 60 years, have become a permanent fixture on the peninsula. Incredibly, South Korean forces remain under US command.

Third, the agreement prohibits “the introduction into Korea of reinforcing combat aircraft, armored vehicles, weapons and ammunition.” The US violated the agreement by introducing nuclear weapons into South Korea in 1958. And it’s questionable whether the war games-related deployment of massive amounts of US military hardware to Korea doesn’t violate the agreement, as well.

What Washington wants from North Korea

On March 11, U.S. national security adviser Tom Donilon announced publicly that what Washington wants from North Korea is open markets and the country’s integration into the US-led system of global capitalist exploitation. At least, that’s what he meant when he said, “I urge North Korea’s leaders to reflect on Burma’s experience.” [7]

Burma (Myanmar) turned its self-directed, locally-, and largely publicly-owned economy into a capitalist playground for foreign investors.

When Myanmar’s military took power in a 1962 coup, it nationalized most industries and brought the bulk of the economy under government control, which is the way it stayed until three years ago. Major utilities were state-owned and health-care and education were publicly provided. Private hospitals and private schools were unheard of.

Ownership of land and local companies was limited to the country’s citizens. Companies were required to hire Myanmar workers. And the central bank was answerable to the government. In other words, Myanmar’s economy, inasmuch as it markets, labor and natural resources were used for the country’s self-directed development, was very much like North Korea’s.

And like North Korea, Myanmar was an object of US hostility, subject to sanctions, and targeted by US-orchestrated low-level warfare.

Bowing to US pressure, Myanmar’s government began in the last few years to sell off government buildings, its port facilities, its national airline, mines, farmland, the country’s fuel distribution network, and soft drink, cigarette and bicycle factories.

The doors to the country’s publicly-owned health care and education systems were thrown open, and private investors were invited in. A new law was drawn up to give more independence to the central bank, making it answerable to its own inflation control targets, rather than directly to the government.

To top it all off, a foreign-investment law was drafted to allow foreigners to control local companies and land, permit the entry of foreign telecom companies and foreign banks, allow 100 percent repatriation of profits, and exempt foreign investors from paying taxes for up to five years. What’s more, foreign enterprises would be allowed to import skilled workers, and wouldn’t be required to hire locally.

With Myanmar signaling its willingness to turn over its economy to outside investors, US hostility abated and the sanctions were lifted. President Obama dispatched then US secretary of state Hillary Clinton to meet with Myanmar’s leaders, the first US secretary of state to visit in more than 50 years.

William Hague soon followed, the first British foreign minister to visit since 1955. Other foreign ministers beat their own paths to the door of the country’s military junta, seeking to establish ties with the now foreign investment-friendly government on behalf of their own corporations, investors, and banks.

And business organizations sent their own delegations, including four major Japanese business organizations, all looking to cash in on Myanmar’s new opening. Announcing the easing of US sanctions, then US secretary of state Hilary Clinton enthused, “Today we say to American business: Invest in Burma!” [8]

That, then, is what the United States wants for North Korea: for a US secretary of state to one day announce. Today we say to American business: “Invest in North Korea!”

Effects, not causes

In the US view, North Korea is a militaristic, aggressive state, bent on provoking South Korea and its American overlords and setting the peninsula aflame, for reasons that are never made clear. Pyongyang must, therefore, be deterred by sanctions and displays of US military’s resolve.

Yet North Korea has never pursued an aggressive foreign policy, hasn’t the means to do so, and unlike the United States and South Korea, has never sent troops into battle on foreign soil. (South Korea hired out its military to the United States as a mercenary force to battle nationalists seeking independence in Vietnam.)

By contrast, the DPRK’s militarism, expressed in its Songun (military first) policy, is defensive, not aggressive, mercenary or imperialist.

It is a misconception that the incursion of North Korean forces into the south in 1950, marking the formal start of the Korean War, was an invasion across an international border.

The boundary dividing the two Koreas had been drawn unilaterally by the United States in 1945, and never agreed to by Koreans.

The Korean War was a civil war in which sovereigntists, and collaborators with the Japanese, now with the Americans, battled over control of their country, aided by foreign militaries. Had the United States not intervened the country would have been re-united under a socialist government committed to independence.

The US view, far from providing an accurate account of North Korea and its relationship with the United States, turns reality on its head.

The reality is that US public policy, including foreign policy, is largely shaped by corporations, banks, and elite investors, through lobbying, the funding of think tanks, and placement of corporate officers, Wall Street lawyers, and ambitious politicians dependent on the wealthy for campaign financing and lucrative post-political job opportunities, into key positions in the state.

US foreign policy seeks to protect and enlarge the interests of the class that shapes it, by safeguarding existing, and securing new, foreign investment opportunities, opening markets abroad for US goods and services, and ensuring business conditions around the world are conducive to the profit-marking imperatives of US corporations.

From the perspective of the goals of US foreign policy, North Korea’s publicly-owned, planned economy commits the ultimate sin: it reserves North Korean labor, markets and natural resources for the country.s own welfare and self-development.

Accordingly, US foreign policy aims to reduce North Korea to such a level of deprivation and misery that the people overthrow their leaders and open the gate, or the leaders capitulate and heed Donilon’s urging to follow Myanmar’s capitulatory path.

All attempts to resist integration into the US-superintended global capitalist system are deceptively presented by the United States as evidence of North Korea’s bellicosity, rather than what they are: acts of self-defense against an imperialist predator.

Stephen Gowans

http://gowans.wordpress.com/2013/03/16/armistice-agreement-withdrawal-north-korean-belligerence/

Notes

1. Tim Beal. Crisis in Korea: America, China and the Risk of War. Pluto Press, 2011, p. 180.

2. U.S. News & World Report, June 26, 2008; The New York Times, July 6, 2008.

3. For more on US threats of nuclear annihilation against North Korea see Stephen Gowans, .Why North Korea needs nuclear weapons., what’s left, February 16, 2013.

4. The combined US-South Korean 2010 military budget was $739B (US, $700B; South Korea, $39K), 74 times greater than North Korea’s $10B expenditure. For more see Stephen Gowans, .Wars for Profits: A No-Nonsense Guide to Why the United States Seeks to Make Iran an

International Pariah,. what’s left, November 9, 2011.

5. Alastair Gale, .Kim’s visit to bases raises tension., The Wall Street Journal, March 12, 2013.

6. New York Times, August 14, 2003.

7. Alastair Gale and Keith Johnson, .North Korea declares war truce .invalid.., The Wall Street Journal, March 12, 2013.

8. On Myanmar’s transition to open markets and free enterprise see Stephen Gowans, .Myanmar learns the lesson of Libya,. what’s left, May 20, 2012.