China’s $9.2 billion precision medicine initiative could see about 100 million whole human genomes sequenced by 2030 and more if sequencing costs drop

China has enlisted the private sector as well as government resources in its bid to make the country a leader in “precision medicine,” a proposed model for the treatment of diseases tailored to individual patients based on their genetic makeup.

The first step will be to assemble a database of genomic data from the Chinese and international populations. A cross-disciplinary team coordinated by the Beijing Institute of Genomics will first collect genetic information from about 2,000 volunteers and aim to develop new treatment concepts.

Wuxi Nextcode, which involved in the PMI, previously provided the database for the national genome projects in the United Kingdom and Qatar as well as the foundation for the rare disease diagnostics and research programmes at Boston Children’s Hospital in the United States and Fudan University Children’s Hospital in Shanghai.

“[We focus on] the application of sequence data to improve disease diagnosis, develop better and more targeted drugs, and to provide informed, personalized scientific wellness regimes that can help people to stay healthier longer,” Sun said.

Meanwhile, Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei Technologies Company will develop cloud infrastructure to facilitate the handling of genomic data associated with the PMI.

Precision medicine is still in its early stages, experts note. “While some advances in precision medicine have been made, the practice is not currently in use for most diseases,” US National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins noted in 2015. (A PMI was launched in the US in January 2015, with a budget of US$215 million for its first year).

China appears determined to be move to the forefront in the field. “China is poised to play a leading role in advancing the most cutting-edge precision medicine in the world,” says Sun. “This includes population genomics, drug discovery, clinical diagnostics, and personal wellness.”

The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) for the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI) — a US$215-million project plans to collect data on genomes, health records and physiological measurements from 1 million participants, to learn how genetics, environment and lifestyle influence disease risk and the effectiveness of treatments.

Genome-sequencing companies are already vying to provide services to deal with the anticipated demand. For several years, China has boasted high genome-sequencing capacity. In 2010, the genomics institute BGI in Shenzhen was estimated to host more sequencing capacity than the entire United States.

This was thanks to its equipment, purchased from Illumina of San Diego, California, which at the time represented state-of-the-art technology. But Illumina has since sold upgraded machines to at least three other genomics firms — WuXi PharmaTech and Cloud Health, both in Shanghai, and the Beijing-based firm Novogene.

Jason Gang Jin, co-founder and chief executive of Cloud Health, says that this trio, rather than BGI, will be the main sequencing support for China’s precision-medicine initiative — although BGI’s director of research, Xu Xun, disagrees.

Xu says that precision medicine is a priority for BGI and that the organization has a diverse portfolio of sequencers that still gives it an edge.

“If you are talking about real data output, BGI is still leading in China, maybe even globally,” he says. BGI has already established a collaboration with the Zhongshan Hospital’s Center for Clinical Precision Medicine in Shanghai, which opened in May 2015 with a budget of 100 million yuan and is run by Fudan University.

Jin thinks that China will be faster than the United States at sequencing genomes and identifying mutations that are relevant to personalized medicine because China’s larger populations of patients for each disease will make it easier to find sufficient numbers to study.

Still, it remains to be seen whether China has the resources to apply these insights to the individualized care of patients.

Researchers at Tsinghua University, Fudan University and the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences are setting up precision medicine centers with Sichuan University’s West China Hospital planning to sequence 1 million human genomes itself, “the same goal as the entire U.S. initiative,” Nature reported.

The larger precision medicine project has 92 times the funding of the Fudan project. If the genome sequencing was scaling with the funding then China could have around 100 million genome sequenced within 15 year.

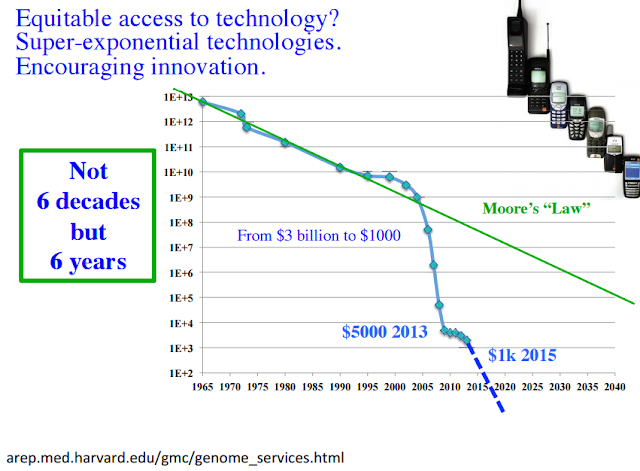

Whole Genome Sequencing costs will soon be below $10 a genome from about $1000 today

If the prices do fall as expected by Harvard Professor and multiple startup founder George Church. The $9.2 billion project could enable the sequencing of everyones genome in China (1.4 billion people) by 2024.

The sequencing of over half of the world’s population (everyone in the developed world and China and parts of other countries seems possible by 2025 and very likely to by 2030. This would enable deep understanding of the correlation between genes and traits.

Effective Human Genome editing using detailed gene knowledge is also on track

George Church indicated that recent research shows that editing sperm stem cells could be the safest approach to genetically editing humans. Jinsong Li, a biologist at the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences has managed to use CRISPR to edit a gene that causes eye cataracts in mice, creating healthy newborn animals with “100 percent” success. Scientists say working with eggs will be harder.

Men produce millions of new sperm a day—clear proof of stem cells at work. But women’s bodies work differently. Women appear to be born with all the eggs they’ll ever have, and biologically, it seems unlikely there is such a thing as an egg stem cell in adults.

Yet other scientists are already developing a work-around. They predict it will eventually be possible to take a skin cell from a woman and use a technology called “reprogramming” to convert it into an artificial egg in the laboratory. And they could make sperm the same way.

That means IVF clinics in the future might take a skin punch from a customer and return either gene-edited eggs or sperm a few weeks later. “There is no reason to think it can’t be done,” says George Daley, a noted stem cell researcher at Harvard University’s medical school. From what he’s seen, he says, the prospect of installing custom DNA edits into lab-grown reproductive cells is “very real.”

Next Big Future

http://nextbigfuture.com/2016/06/chinas-92-billion-precision-medicine.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A%20blogspot%2Fadvancednano%20%28nextbigfuture%29