“This global observance is to raise awareness of the major problem that illicit drugs represent to society” United Nations

By resolution 42/112 of 7 December 1987, the UN General Assembly decided to observe 26 June as the International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking as an expression of its determination to strengthen action and cooperation to achieve the goal of an international society free of drug abuse.

Raise awareness?

Rarely acknowledged, (“legal”) drug trafficking was initiated by the British Empire. There is continuity. The colonial label has been scrapped. Today the (“illicit”) drug trade is a multibillion dollar operation.

The two main hubs of production today are:

- Afghanistan which produces approximately 90% of the World supply of opium (transformed into heroin and opioid related products). There was a successful drug eradication programme in 2000-2001 which was initiated (with UN support). prior to the US-NATO led invasion in October 2001. Since the invasion and military occupation, according to UNODC, the production of opium has increased 50 fold, reaching 9000 metric tons in 2017.

- The Andean region of South America (Colombia, Peru, Bolivia) which produces cocaine. Colombia is a US supported narco-state.

The Drug Economy is an integral part of Empire Building. Drug trafficking is protected by the US military and intelligence apparatus.

(This will be the object of several Global Research articles which will be published in the next few days in support of the June 26, 2020 UN sponsored “global observance to raise awareness”).

The Role of the British Empire

Historically, drug trafficking was an integral part of British colonialism. It was “legal”.

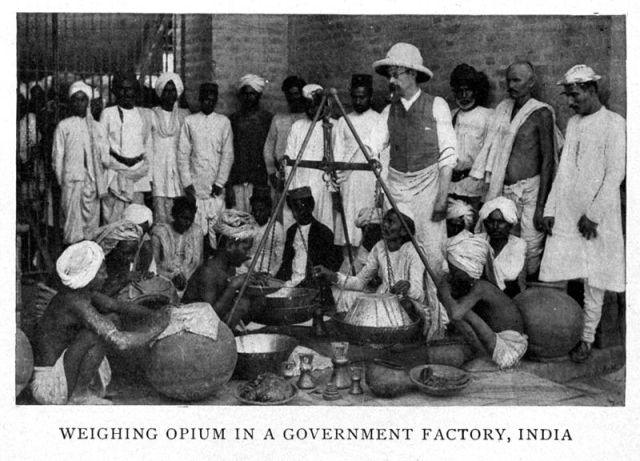

Opium produced in Bengal by the British East India Company (BEIC) was shipped to China’s Southern port of Canton.

The state-sponsored export of opium from British India to China was arguably the largest and most enduring drug operation in history. At its peak in the mid-19th century it accounted for roughly 15% of total colonial revenue in India and 31% of India’s exports. To supply this trade the East India Company (EIC) – and later the British Government – developed a highly regulated cultivation system in which over one million farmers a year were under contract to grow opium poppies. …

The agency system ensured that farmers did not share in the large profits of the opium trade. Given their monopsony power, the opium agencies were able to “keep the price of crude opium just on the economic edge” (Jonathan Lehne, 2011)

While the share of agricultural land allocated to opium was comparatively small, opium production under colonial rule was nonetheless conducive to impoverishing the Indian population, destabilizing the agriculture system as well as triggering numerous famines.

According to an incisive BBC report:

“The cash crop [opium] occupied between a quarter and half of a peasant’s holding. By the end of the 19th Century poppy farming had an impact on the lives of some 10 million people in what is now the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

The trade was run by the East India Company, the powerful multinational corporation established for trading with a royal charter that granted it a monopoly over business with Asia. This state-run trade was achieved largely through two wars, which forced China to open its doors to British Indian opium. …

Stiff production targets fixed by the Opium Agency also meant farmers – the typical poppy cultivator was a small peasant – could not decide whether or not to produce opium. They were forced to submit part of their land and labour to the colonial government’s export strategy”.

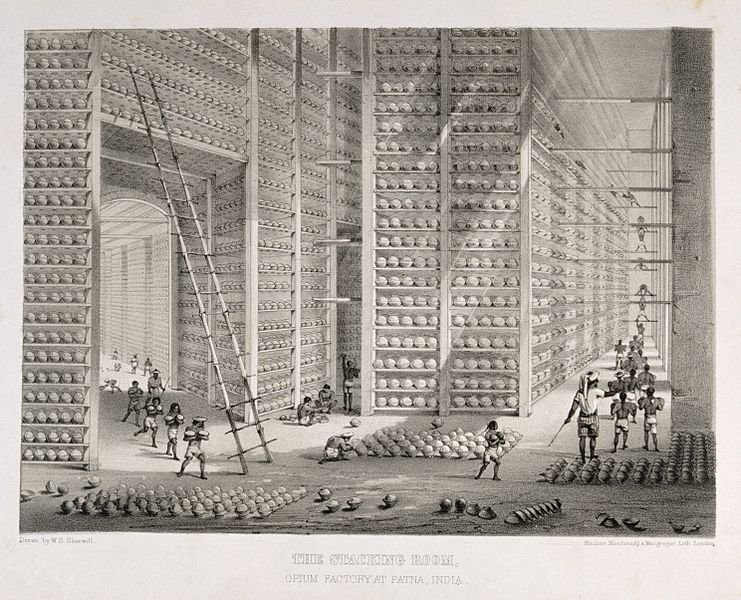

BEIC Opium Factory and Stacking Warehouse, Patna, 1850s

China and the Opium Wars

When China’s Qing Emperor Daoguang ordered the destruction of opium stocks in the port of Canton (Guangzhou) in 1838, the British Empire declared war on China on the grounds that it was obstructing the “free flow” of commodity trade.

The term “trafficking” applies to Britain. It was condoned and supported throughout the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901). In 1838, 1,400 tons of opium per annum were exported from India to China. In the wake of the First Opium war, the volume of these shipments (which extended until 1915) increased dramatically.

The so-called first opium war (1838-1842), which represented an act of aggression against China was followed by the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing, which not only protected British imports of opium into China, it also granted extraterritorial rights to Britain and other colonial powers leading to the formation of the “Treaty Ports”.

The massive revenues of the opium trade were then used by Britain to finance its colonial conquests. Today it would be called the “laundering of drug money”. The channeling of opium revenues was also used to finance the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank (HKSB) established by the BEIC in 1865 in the wake of the first opium war.

In 1855, Sir John Bowring on behalf of the British Foreign Office negotiated a treaty with King Mongkut (Rama IV) of Siam, entitled The Anglo-Siamese Treaty of Friendship and Commerce (April 1855) which allowed for the free and unrestricted import of opium into the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand).

While Britain’s trade in opium with China was abolished in 1915, Britain’s drug trafficking monopoly continued until India’s Independence in 1947. Affiliate companies of the BEIC such as Jardine Matheson played an important role in the drug trade.

Racism, Narcotics and Colonialism

Historians have focussed on the Atlantic Triangular Slave Trade: slaves from Africa exported by colonial powers to the Americas, followed by commodities produced in plantations using slave labour exported back to Europe.

Britain’s colonial drug trade had a similar triangular structure. Opium produced in colonial plantations by impoverished farmers in Bengal was exported to China, the revenues of which (paid in silver coins) were used largely to finance Britain’s imperial expansion including mining in Australia and South Africa.

No compensation was paid to the victims of the British Empire’s drug trade. The impoverished farmers of Bengal.

Together with the Atlantic slave trade, colonial drug trafficking constitutes a crime against humanity.

Both the Slave Trade and Drug Trafficking were sustained by racism. in 1877, Cecil Rhodes put forth a “secret project” which consisted in integrating the British and US empires into a single Anglo-Saxon Empire:

“I contend that we are the finest race in the world … Just fancy those parts that are at present inhabited by the most despicable specimens of human beings… Why should we not form a secret society… for making the Anglo-Saxon race but one Empire…

Africa is still lying ready for us it is our duty to take it. … It is our duty to seize every opportunity of acquiring more territory and we should keep this one idea steadily before our eyes that more territory simply means more of the Anglo-Saxon race, more of the best the most human, most honourable race the world possesses.

There is continuity from the colonial style legitimate “drug war” led by the British Empire, to the present drug trafficking structures: Afghanistan under US military occupation, the Narco-State in Latin America.

Today, drug trafficking is a multi-trillion dollar business. The UN office on drugs and crime estimates the laundering of drug money and other criminal activity to be of the order of 2-5 percent of Global GDP, $800 billion to $3 trillion. Drug money is laundered through the global banking system.

Remember the Crack Cocaine scandal revealed in 1996 by journalist Gary Webb. Crack was sold to the African-American communities in Los Angeles.

Remember the Crack Cocaine scandal revealed in 1996 by journalist Gary Webb. Crack was sold to the African-American communities in Los Angeles.

Since 2001, the retail sale of heroin and opioids has become increasingly “weaponized” directed against sustaining racism, poverty and social inequality.

While today’s drug trade is the source of wealth and enrichment, drug addiction including the use of heroin, opioids and synthetic opioids has skyrocketed In 2001, 1,779 Americans were killed as a result of heroin overdose. By 2016, heroin addiction resulted in 15,446 deaths.

Those lives would have been saved had the US and its NATO allies NOT invaded and occupied Afghanistan in 2001.

See our forthcoming articles on drug abuse and “Illicit Trafficking”.

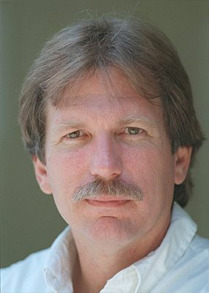

Articles by: Prof Michel Chossudovsky

Michel Chossudovsky is an award-winning author, Professor of Economics (emeritus) at the University of Ottawa, Founder and Director of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG), Montreal, Editor of Global Research. He has taught as visiting professor in Western Europe, Southeast Asia, the Pacific and Latin America. He has served as economic adviser to governments of developing countries and has acted as a consultant for several international organizations. He is the author of eleven books including The Globalization of Poverty and The New World Order (2003), America’s “War on Terrorism” (2005), The Global Economic Crisis, The Great Depression of the Twenty-first Century (2009) (Editor), Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War (2011), The Globalization of War, America’s Long War against Humanity (2015). He is a contributor to the Encyclopaedia Britannica. His writings have been published in more than twenty languages. In 2014, he was awarded the Gold Medal for Merit of the Republic of Serbia for his writings on NATO’s war of aggression against Yugoslavia. He can be reached at crgeditor@yahoo.com

The original source of this article is Global Research

The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.