The goal of life is living in agreement with nature. Zeno

The world is not to be put in order. The world is order. It is for us to put ourselves in unison with this order. Henry Miller

Man’s heart away from nature becomes hard. Standing Bear

Introduction

The history of folklore as an area of study is relatively recent compared to its ancient origins. In the eighteenth century the role of Enlightenment science in changing attitudes towards the study of folklore soon showed benefits with an increased understanding of ourselves and our history of survival throughout the centuries. Soon, the influence of nationalist Romanticism paved the way for much research and support for folklore as an integral part of every country’s cultural heritage in the nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century folklore had moved from being the culture of ‘backward peoples’ to becoming a major tool in the hands of the state, leading to very different approaches to folklore in the Soviet Union and Germany in the 1920s and 1930s. Post World War 2 and the decline of nationalism, folklore and folk music have taken a back seat in the spread of globalised cosmopolitan commercialism.

However, the anxiety over the rapid pace of the destruction of nature (land, forests, wildlife, and seas) in the twenty-first century paves the way for a re-evaluation of folklore, not as an ancient tradition that was perceived to be replaced by science in the nineteenth century, but as a pro-nature ideology that was cleverly replaced by anti-nature industrialisation, thereby choking off its continuing relevance as an important part of our cultural and political struggle to end the ruination of the planet.

History of folklore

Folklore is generally defined as the traditions common to a culture, subculture or group of people. It encompasses oral traditions such as tales and legends, material culture such as traditional building styles and customary lore such as the forms and rituals of Christmas, weddings, folk dances and initiation rites. Folklore is transmitted from place to another or one generation to the next and these traditions tend to be passed informally from one person to another through demonstration or verbal instruction.

In 1846, the British writer W. J. Thoms invented the word ‘folklore’ to replace ‘popular antiquities’ or ‘popular literature’. The meaning of ‘folk’ at the time generally meant rural, poor and illiterate peasants. ‘Lore’ comes from Old English lār ‘instruction’, the knowledge and traditions of a particular group, frequently passed along by word of mouth.

The initial basis for the study of folklore derived from changing ideas about the peasantry who were seen to be losing their culture in the fast developing process of industrialisation. During the Enlightenment, the philosopher, Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744–1803), not only wrote about the importance of the nation and patriotism but he also gave the idea of the ‘people’ a new significance when he stated that “there is only one class in the state, the Volk, (not the rabble), and the king belongs to this class as well as the peasant”. If the people were defined as significant (not backward and uncultured), then their culture and folk traditions were also significant and necessary for the process of nation building.

Thus, local traditions and rituals which were largely ignored previously were transformed into an area of culture and history that could be studied, and “from the 1860s there was a boom in the collection and discussion of folklore – the rise of social Darwinism, a growing population and increased urbanisation generated an upsurge in the idea of survivalism and a fear that these rural traditions might be lost.” In England, the first female president of the Folklore Society, Charlotte Sophia Burne (1850–1923) defined folklore as:

‘the generic term under which the traditional Beliefs, Customs, Stories, Songs and Sayings current among backward peoples, or retained by the uncultured classes of more advanced peoples, are comprehended and included.’

As we can see from this quote, folklore was perceived as “relics of behaviour from the distant past” that has been passed down through the generations. The middle and upper classes, largely the beneficiaries of industrialisation, had a background of success and wealth that buttressed their view of the working class and peasantry as the ‘uncultured classes’. In many countries the changes in society brought about by industrialisation created an anxiety about cultural loss:

“Encroaching modernity caused the Victorians to worry that old traditions were under threat and in need of preservation. A rising panic at the changes wrought by technology, industrialisation, and burgeoning capitalism collided with fears about the booming population and the move to city life, creating a nostalgia for the rural idyll. It was against this backdrop that an interest in recording folklore grew, alongside an anxiety that it was a way of life quickly passing.”

Peko (Finnish spelling Pekko, Pekka, Pellon Pekko) is an ancient Estonian and Finnish god of crops, especially barley and brewing.

Enlightenment

The Enlightenment approach to folklore involved a “systematic, scientific study of behaviour – the folklore collected dispassionately for future analysis” and, moreover, the benefits of such study were quickly becoming apparent:

“Nobody now disputes that the superstitions, the customs, the tales, the songs, and even the proverbial sayings of a people may throw unexpected light upon its history; and from the investigation and comparison of such things as these, once deemed unworthy of notice, scientific men have begun to reconstruct the unrecorded past of humanity.”

The new interest in mythology and folklore also became a tool in the hands of Enlightenment rationalists and skeptics who used it to undermine Christianity and the Church. As Robert D. Richardson noted:

“When Pierre Bayle scoffs at the story of Athena being born without the aid of a mother from the head of Jupiter, he does it in such a way as to emphasize the story’s similarity to that of Christ’s having been born without the aid of a mortal father. If we smile at the miracles in Greek mythology, how can we not smile at similar miracles in the Bible?”

The Enlightenment View of Myth and Joel Barlow’s “Vision of Columbus” Author(s): Robert D. Richardson, Jr.

However, the study of folklore and mythology also revealed ancient and pre-Christian beliefs centered around a profound respect and worship of nature. In his book The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, the Scottish anthropologist Sir James George Frazer (1854–1941) speculated that: “shared elements of religious belief and scientific thought, discussing fertility rites, human sacrifice, the dying god, the scapegoat, and many other symbols and practices whose influences had extended into 20th-century culture.” Frazer’s thesis was that “old religions were fertility cults that revolved around the worship and periodic sacrifice of a sacred king.” Frazer proposed that “mankind progresses from magic through religious belief to scientific thought.”

Prajapati with similar iconographical features associated with Brahma, a sculpture from Tamil Nadu.

Prajapati’s role varies within the Vedic texts such as being one who created heaven and earth, all of water and beings, the chief, the father of gods, the creator of devas and asuras, the cosmic egg and the Purusha (spirit).

Romantic nationalism

With the rise of Romantic nationalism during the nineteenth century, folklore took on a new significance as the ‘soul’ of the people. The nation state claimed its political legitimacy based on an organic unity of the people which in turn was based on elements such as “language, race, ethnicity, culture, religion, and customs of the nation in its primal sense of those who were born within its culture.” This unity from below was emphasised by nationalists in reaction to the dynastic or imperial hegemony of feudalism which claimed its authority from above, for example, the divine right of kings who were mandated by God to rule over the people.

Folklore was useful to nationalists from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, not only to counter the old ideology of monarchy but it also served to counter the future threat of socialist ideas. For nationalists, the rural-based folklore of the people could form the basis of a class-conciliatory popular ideology in opposition to the spreading socialist concepts of working class culture, class warfare and revolution among the radicals. The rise of the socialist movements, culminating in the creation of Soviet Russia in 1917 heralded both positive and negative views of folklore.

Xochiquetzal, from the Codex Rios, 16th century.

In Aztec mythology, Xochiquetzal was a goddess associated with fertility, beauty, and love, serving as a protector of young mothers and a patroness of pregnancy, childbirth, and the crafts. Worshipers wore animal and flower masks at a festival, held in her honor every eight years.

The Soviet Union

Folklore studies thrived in the Soviet Union in the 1920s as there was little state control and the government was more concerned with the new economy, trying to reverse decades of underdevelopment. However, by the late 1920s the Soviet government “repressed Folklore, believing that it supported the old tsarist system and a capitalist economy.” Stories about feudal princes and princesses eventually came under criticism by the Soviet government:

“They saw it as a remnant of the backward Russian society that the Bolsheviks were working to surpass. To keep folklore studies in check and prevent inappropriate ideas from spreading amongst the masses, the government created the RAPP – the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers. The RAPP specifically focused on censoring fairy tales and children’s literature, believing that fantasies and “bourgeois nonsense” harmed the development of upstanding Soviet citizens. Faerie tales were removed from bookshelves and children were encouraged to read books focusing on nature and science.”

A new way of seeing folklore was developed that put emphasis on “traditional legends and faerie tales [that] showed ideal, community-oriented characters, which exemplified the model Soviet citizen” in particular “tales that showed members of the working class outsmarting their cruel masters, again working to prove folklore’s value to Soviet ideology and the nation’s society at large.”

Certain customs were changed (in terms of content) or adapted (in terms of form), for example, the Christmas tree. In Russia, the tradition of installing and decorating a Yolka (tr: spruce tree) for Christmas was very popular but fell into disfavor (as a tradition originating in Germany – Russia’s enemy during World War I) and was subsequently banned by the Synod in 1916. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, Christmas celebrations and other religious holidays were prohibited under the Marxist-Leninist policy of state atheism in the Soviet Union. Although the Christmas tree was banned, people continued the tradition with New Year trees which eventually gained acceptance in 1935:

“The New Year tree was encouraged in the USSR after the famous letter by Pavel Postyshev, published in Pravda on 28 December 1935, in which he asked for trees to be installed in schools, children’s homes, Young Pioneer Palaces, children’s clubs, children’s theaters and cinemas.”

The Yolka tree remains an essential part of the Russian New Year traditions when Ded Moroz or ‘Grandfather Frost’ (with assistance from his granddaughter Snegurochka,’Snow Maiden’), like Santa Claus, brings presents for children to put under the tree or to distribute them directly to the children on New Year’s morning performances. Thus, native folklore and traditions in Russia and the Soviet Union were customised to suit the changing material conditions of society in a rational process of adaptation that contrasted sharply with the irrationalist over-importance given to them in Nazi Germany.

In Māori mythology, Rongo or Rongo-mā-Tāne (also Rongo-hīrea, Rongo-marae-roa,[1] and Rongo-marae-roa-a-Rangi[2]) is a major god (atua) of cultivated plants, especially kumara (spelled kūmara in Māori), a vital crop.

National socialism

The rise of the national socialists in Germany in the 1930s also shifted folklore in a new direction as the Nazis not only linked the concept of peasant folklore with that of national unity, but looked abroad for suitable models (the “strong and heroic” Nordic tradition), despite feeling ‘guilty’ about the ‘foreign elements’ in German folklore:

“After 1935, German folklore professors were under pressure adapt their theories and findings to the National Socialist Weltanschauung [worldview]. This not only implied the obligation to join in the search for Nordic-Germanic symbols at the expense of other interests, but it also meant giving priority to those elements that might be of immediate ideological usefulness to the Party.” [1]

According to the German anti-Nazi philosopher Ernst Bloch, “Hitler painted the ethnic heterogeneity of Germany as a major reason for the country’s economic and political weakness, and he promised to restore a German realm based on a cleansed, and hence strong, German people.”

Folklore, as part of the ideology of German national self-consciousness, became a way of reading and understanding history itself:

“The social and religious order of the Nordic-Germanic tribes, they claimed, was the order of the present and, certainly, the order of the future. In their effort to strengthen the German national self-consciousness, the Nazi ideologists emphasized not only an identification with the heroic age but also a deep contempt for the Roman civilization. In their view, the glorification of Rome and everything Roman had led to a serious weakening of Germany’s folk unity. The “healthy” resources of Germany’s own past had been sacrificed to the admiration of Rome.” [2]

This Romanticist, irrationalist view of history (and ‘folk unity’) was part of the glorification of the peasant as the repository of the primary culture of traditional heritage. The peasant, previously seen as backward and uncultured, was now held up as the ideal model for society and culture as elites worried about the growth of the working class. The study of folklore was also reduced to a limited racial point of view to justify German ‘superiority’ that would underpin the German elite’s desire to conquer Europe.

Overall we can see that in the twentieth century folklore and myth served multiple purposes in differing political ideologies of nationalism, national socialism, and socialism.

Susanoo (スサノオ; historical orthography: スサノヲ, ‘Susanowo’) is a kami in Japanese mythology. The younger brother of Amaterasu, goddess of the sun and mythical ancestress of the Japanese imperial line, he is a multifaceted deity with contradictory characteristics (both good and bad), being portrayed in various stories either as a wild, impetuous god associated with the sea and storms, as a heroic figure who killed a monstrous serpent, or as a local deity linked with the harvest and agriculture.

Folklore past, present, and future

In the past, our ideas about folklore were defined as traditional or modern by contrasting Enlightenment and Romanticist theories that revealed differing concepts of time. As Diarmuid Ó Giolláin writes:

“The traditional and the modern are usually understood to be in a negative relationship to one another, the one looking backwards, the other forwards, the one static, the other dynamic, the one repetitive and the other innovative. The notion of time in traditional societies is understood as being repetitive and circular; reflecting the rhythms of nature, with the events of the beginning of time constantly being reactualised through myth and ritual, while time in the historic religions and in modern societies is seen as linear and irreversible.” [3]

The linear view is teleological, encompassing patriarchal religion and capitalism that only moves in one direction (towards the Day of Judgement), and with growth as its model, despite the fact that we live in a world of limited resources. In opposition to this view, there is the circular view of time in traditional societies which reflected the ever-changing seasons and respect for nature.

The idea of linear time is reflected in Frazer’s view of folklore as being on a continuum “from magic through religion to science”. However, this is a sleight of hand that misses the point that folklore has been an important part of pre-Christian, pagan, and pro-nature ideology that was not replaced by science, but instead by an anti-nature ideology that uses science to justify and legitimise its industrial-scale extractivism and exploitation of nature.

The difference between folklore and science was not an epistemological difference (tradition v science) but a consequence of capitalist exploitation that operates through the destruction of nature and then tried to legitimate itself by hiding in a cloak of modernity, while at the same time negating past pro-nature practices. There was no reason why the pro-nature continuum of folklore could not have been seen as one that continued to the present and on into the future, as people’s connection with nature had not fundamentally changed (nature being, of course, the vital source of our sustenance).

Our unchanged relationship with nature can be seen in the continuation of practices associated with folklore, the culture of respect and reverence towards nature, such as Hallowe’en, Easter eggs and hares, Christmas trees, and bonfires (as a few Western examples), despite increasing commercialisation.

A similar argument was made that portrait painting was ‘outmoded’ by photography (a very different and mechanical process), yet portraiture has continued to today in full strength with national portrait galleries and portrait competitions. The importance of portraiture lies in its ability to evoke emotions beyond the literal interpretation of the subject, making the person who views a portrait feel something, which connects them to the artist’s feelings, thoughts and desires.

The anti-nature continuum of the wilful exploitation of nature (such as the ongoing destruction of the Amazon and wildlife, the global and mass use and abuse of animals, transnational polluting industries, chemical-driven industrial crop land, and factory ship over-fishing that is emptying our seas) also continues to today in parallel with traditional pro-nature folklore customs and traditions.

The conflict between industrialisation of nature and respect for nature is sharply highlighted by Yuval Noah Harari when he writes:

“The fate of industrially farmed animals is one of the most pressing ethical questions of our time. Tens of billions of sentient beings, each with complex sensations and emotions, live and die on a production line. Animals are the main victims of history, and the treatment of domesticated animals in industrial farms is perhaps the worst crime in history.”

The importance of folklore is not that it ties us in with our past, but that it connects us into an understanding of nature in a meaningful way. If there is a distance between people and nature, it is as a result of an unfortunate coincidence of certain groups and the location of fossil fuels globally, as Michael Cronin writes:

“It is often the poorest people on the planet speaking lesser-used languages in more remote parts of the world that find themselves at the frontline of the race to extract as much fossil fuel resources as possible from the earth. […] Bram Buscher, a geographer, has coined the term ‘liquid nature’ to describe the way in which fields, forests and mountains lose there intrinsic, place-based meaning and become deracinated, abstract commodities in a global trading system.” [4]

Cronin quotes Russ Rymer on the importance of local knowledge built up over generations:

“When small communities abandon their languages and switch to English or to Spanish, there is a massive disruption in the transfer of traditional knowledge across generations – about medicinal plants, food cultivation, irrigation techniques, navigation systems, and seasonal calendars.” [5]

Cronin points to the importance of local knowledge contained in the Irish language (an ancient but threatened language), for example, which has “linguistic resources in abundance”, [6] and is particularly important in the “shift from an ideology of extractivism [anti-nature] to an ideology of regeneration [pro-nature]”. [7]

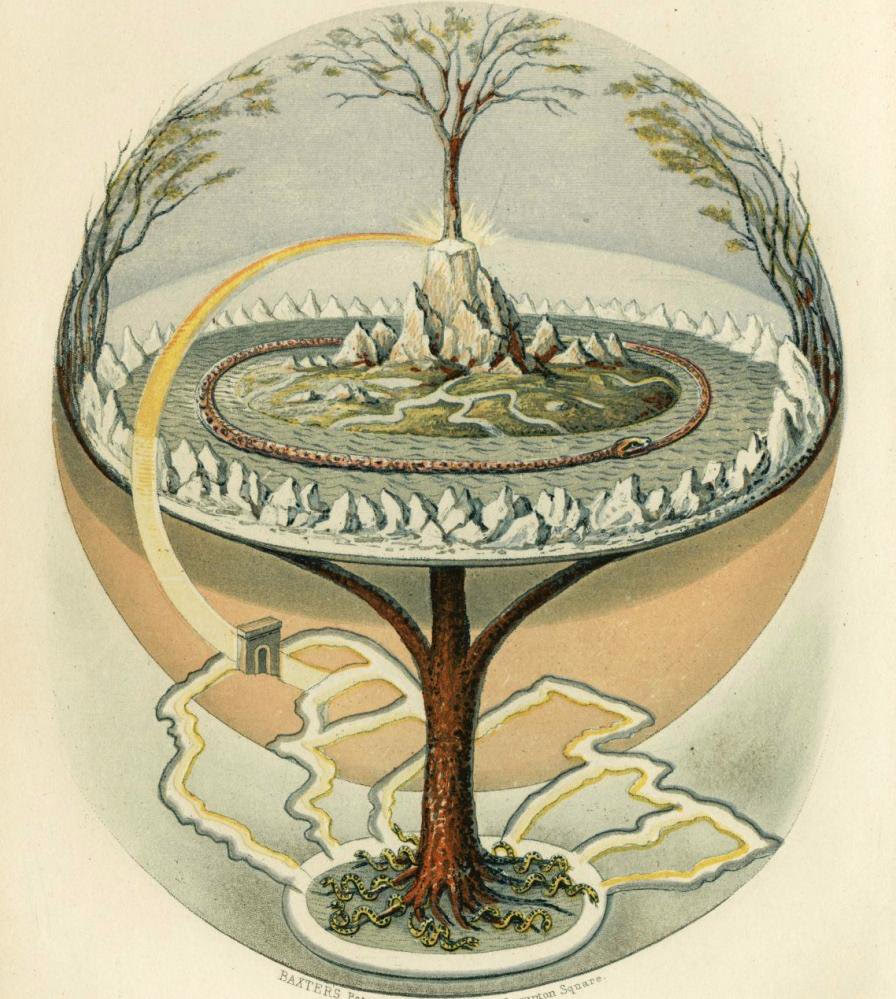

Yggdrasil (from Old Norse Yggdrasill [ˈyɡːˌdrɑselː]), in Norse cosmology, is an immense and central sacred tree. Around it exists all else, including the Nine Worlds. Yggdrasil is an immense ash tree that is central to the cosmos and considered very holy. The gods go to Yggdrasil daily to assemble at their traditional governing assemblies, called things.

Folklore of sacred trees

The strong connection between people and nature has never gone away, and can be seen in past and present attitudes towards trees, for example. In a recent development in Co. Cork in southern Ireland a local Christmas tree grower now rents his Christmas trees. The grower gives the renter instructions on the care of the tree and it is returned to him in January, when it is re-potted and numbered. Why? Because many who rent the trees wish to have the same tree returned to them in the following year.

This emotional connection with trees has a long history on a global scale. Helen Keating gives nine examples of English tree lore: “Our lives have been so closely linked with trees since prehistoric times, they’ve been the subjects of legends, folklore and mythology.” Zteve T Evans looks at examples of Irish tree folkore: “It is believed that the ancient Celtic people were animists who considered all objects to have consciousness of some kind. This included trees, and each species of tree had different properties which might be medicinal, spiritual or symbolic. […] Some species of tree featured in stories from their myths, legends and folklore.”

J. A. MacCulloch noted that:

“Pliny said of the Celts: “They esteem nothing more sacred than the mistletoe and the tree on which it grows. But apart from this they choose oak-woods for their sacred groves, and perform no sacred rite without using oak branches. […] A people living in an oak region and subsisting in part on acorns might easily take the oak as a representative of the spirit of vegetation or growth. It was long-lived, its foliage was a protection, it supplied food, its wood was used as fuel, and it was thus clearly the friend of man. For these reasons, and because it was the most abiding and living thing men knew, it became the embodiment of the spirits of life and growth.”

The global belief in tree deities demonstrates the ancient awareness of the value of trees for our existence and survival in folklore. We are becoming acutely aware of the importance of trees today with modern science giving us much knowledge of forests as carbon sinks, showing there is no conflict between science and folklore but, in fact, a major conflict between pro- and anti- nature ideologies, as the destruction of nature continues unabated. All over the world today the wealth of folklore is being developed and added to through collection and research. People everywhere participate in and learn about their country’s folklore through their education systems as well as their family and community traditions. However, we need a major re-evaluation of folklore, not as an atavistic return to pagan primitivism, but as an important step in returning our societies back to the pro-nature philosophy and consciousness of our ancestors. Our survival as a species depends on it.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here. Caoimhghin has just published his new book – Against Romanticism: From Enlightenment to Enfrightenment and the Culture of Slavery, which looks at philosophy, politics and the history of 10 different art forms arguing that Romanticism is dominating modern culture to the detriment of Enlightenment ideals. It is available on Amazon (amazon.co.uk) and the info page is here.

Published by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.com

Notes

[1] ‘Folklore as a Political Tool in Nazi Germany’ by Christa Kamenetsky, p221 (The Journal of American Folklore, Jul. – Sep., 1972, Vol. 85, No. 337 (Jul. –

Sep., 1972), pp. 221-235 Published by: American Folklore Society)

[2] ‘Folklore as a Political Tool in Nazi Germany’ by Christa Kamenetsky, p227 (The Journal of American Folklore, Jul. – Sep., 1972, Vol. 85, No. 337 (Jul. –

Sep., 1972), pp. 221-235 Published by: American Folklore Society)

[3] ‘ Rethinking (Irish) Folklore in the Twenty-First Century’ by Diarmuid Ó Giolláin, p39 (Béaloideas, 2013, Iml. 81 (2013), pp. 37-52, An Cumann Le Béaloideas Éireann/Folklore of Ireland Society)

[4] Irish and Ecology by Michael Cronin (Foras na Gaeilge, 2019) p13/14

[5] Irish and Ecology by Michael Cronin (Foras na Gaeilge, 2019) p20

[6] Irish and Ecology by Michael Cronin (Foras na Gaeilge, 2019) p39

[7] Irish and Ecology by Michael Cronin (Foras na Gaeilge, 2019) p32/33