Washington and its allies have failed to arrest the development of Kim’s arsenal, analysts warn

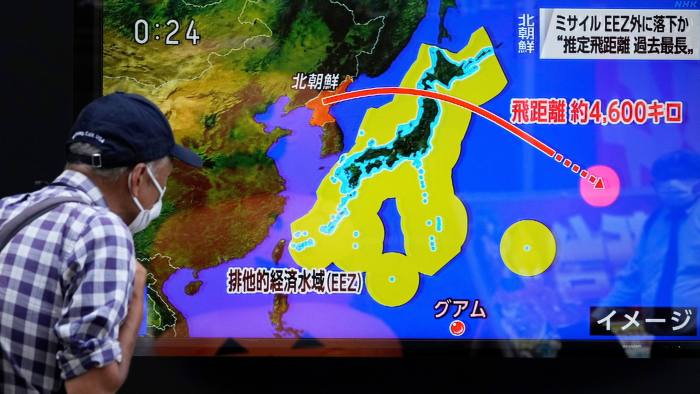

North Korea launched a ballistic missile over Japan on Tuesday for the first time since 2017, sparking alarm in Washington, Tokyo and Seoul © Kimimasa Mayama/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

North Korea launched a ballistic missile over Japan on Tuesday for the first time since 2017, sparking alarm in Washington, Tokyo and Seoul © Kimimasa Mayama/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

The US should admit defeat in its campaign to persuade North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons and focus on risk reduction and arms control measures instead, experts have urged.

On Tuesday, North Korea fired a ballistic missile over Japan for the first time since 2017, sparking renewed condemnation from Washington and its allies.

The US and South Korea responded by conducting joint military drills and firing missiles into the Sea of Japan, while the USS Ronald Reagan, an American nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, conducted a rare U-turn to return to waters east of the Korean peninsula after a recent visit.

But analysts said the military gestures and combative words emanating from Washington, Seoul and Tokyo belied the reality that they have run out of ideas and options for containing North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme.

Experts argued that the US and its allies should focus on agreeing with Pyongyang steps to reduce the risk of a conflict on the Korean peninsula, even if doing so amounted to a tacit acceptance that North Korea would continue to possess nuclear weapons.

“Insistence on denuclearisation is not just a failure, it has turned into a farce,” said Ankit Panda, a nuclear weapons expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

“They test, we respond, we move on with our lives,” Panda added. “North Korea has already won. It’s a bitter pill, but at some point we’re going to have to swallow it.”

South Korea and the US conducted joint military drills in response to North Korea’s latest weapons test. Analysts said an arms race in Asia made it unlikely Pyongyang would agree to denuclearise © South Korean Defence Ministry/AFP/Getty Images

US and Korean officials insisted that even a tacit acceptance of North Korea’s status as a nuclear-armed state would have dangerous consequences for global non-proliferation efforts.

Last month, Kim Jong Un amended North Korea’s nuclear doctrine to allow for pre-emptive strikes. The previous policy only permitted the use of nuclear weapons in a second-strike scenario.

“There will never be any declaration of ‘giving up our nukes’ or ‘denuclearisation’, nor any kind of negotiations or bargaining to meet the other side’s conditions,” the North Korean leader declared.

“As long as nuclear weapons exist on earth and imperialism remains . . . our road towards strengthening nuclear power won’t stop.”

Jenny Town, director of the 38 North programme at the Stimson Center think-tank in Washington, said “the window for a denuclearisation-led process has closed”.

Town pointed to the intensifying arms race in east Asia and increasing tensions between the US and China. “It’s unrealistic to think in the middle of all this, North Korea will contemplate denuclearisation when everyone else, including South Korea, is arming up,” she said.

“Once the relationship is better and the geopolitical trends shift in a more positive direction, maybe we can talk about the nuclear programme again. But that seems way far down the line.”

Andrei Lankov, professor of history at Kookmin University in Seoul and a pre-eminent North Korea expert, said “Kim’s message is as follows: ‘We have nukes, we will have them forever and we will use them as we see fit.’”

Lankov argued that Pyongyang would not countenance talks as long as Washington maintains North Korea’s denuclearisation even as a distant policy goal, while Congress and the US public will not accept anything less than a North Korean capitulation on the issue.

“The US public wants its government to pursue an unobtainable and dangerous dream, but the North Koreans have made clear they are not going to play this game,” said Lankov.

“The only way to persuade them to consider restrictions on their nuclear weapons will be to pay them obscenely well for it.”

North Korea has eschewed diplomacy since 2019, when the last of a series of summits between Kim and then-US president Donald Trump collapsed in Hanoi.

In January 2021, Kim outlined the capabilities he intended to obtain within five years, including tactical nuclear weapons, manoeuvrable missiles, solid fuel ICBMs and nuclear submarines.

Weapons experts said the North Korean regime has made considerable progress on multiple fronts, despite tough international sanctions and Kim sealing the country’s borders in 2020 in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Co-operation between the permanent members of the UN Security Council on North Korea has also broken down in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, further alleviating pressure on Pyongyang.

North Korea has also seized on Russia’s international isolation to foster closer ties with Moscow. On Wednesday, the Security Council failed to condemn Pyongyang’s missile launch after Russia and China blamed Washington for ignoring North Korean security concerns.

“Most senior US officials working on North Korea policy now privately recognise that denuclearisation isn’t going to happen, but can’t or won’t say it publicly,” said Chad O’Carroll, founder of the Korea Risk Group consultancy.

Panda noted that policymakers should be especially worried by North Korea’s development of low-yield tactical nuclear weapons that could be deployed against South Korea.

“A nuclear war might end with an ICBM, but it is more likely to begin with a tactical nuke — they are incredibly dangerous and concerning,” said Panda. “This could be the capability that Kim is waiting for before turning to nuclear coercion or territorial revisionism against the South.”

He said the longer Washington waited before acknowledging the reality that North Korean nuclear weapons were here to stay, the larger and more sophisticated Pyongyang’s arsenal would become, and the higher the cost that Kim would be able to extract in an inevitable future negotiation.

“It is not in the US national interest to let this fester,” Panda said.

Originally published by Financial Times on October 9, 2022.

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.com.