Global War against Russia Takes New Turn: China Attacks Australian Coal, Favors Russian Coal

Last Thursday the government in Beijing struck a new blow against the domination of global commodity markets by countries allied with the US in the sanctions war against Russia.

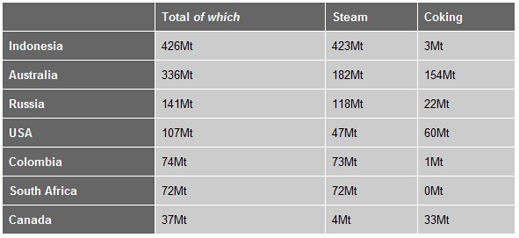

The measure announced is a 3% to 6% tariff to be imposed on coal imports to China, commencing on October 15. Australia, the largest supplier of coal to China, will take the largest hit in its trade. Indonesia, the second largest coal supplier to China, will be exempt as a member of the free trade zone between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

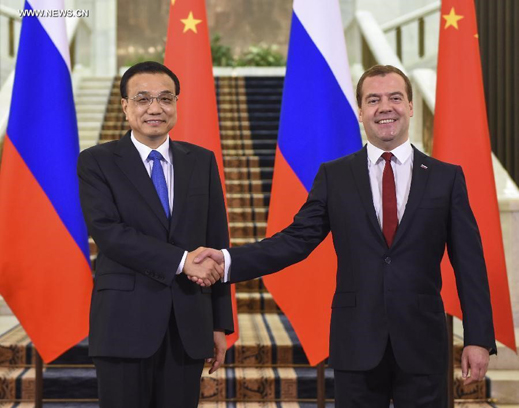

Russia and South Africa, the next largest coal exporters to China, are allied with China in the BRICS geopolitical group: they are to benefit, too. Russian officials and industry sources confirm that negotiations on tariff relief are underway in Moscow this week as Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev met his counterpart, Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang.

The Russian sources are tight-lipped about what will happen next. A spokesman for the Ministry of Energy said it can’t comment now because decisions on the coal import tax have “not yet been finalized”.

Prime Ministers Li and Medvedev in Moscow on Tuesday

The 6% Chinese tariff will be applied to thermal or steam coal, which is used to power electricity turbines. The smaller tariff will apply to the more expensive metallurgical or coking coal, which is used to produce steel. Australian steam coal, which was fetching $90 per tonne last December, had dropped below $66 per tonne last week. The import duty will add an estimated $3 per tonne to the price.

Top Coal Exporters in the World (2013)

Source: http://www.worldcoal.org

According to Russian Customs data for the nine months to September 30, China has taken 19.9 million tonnes of Russian coal so far, worth $1.6 billion. The United Kingdom follows, with 18 million tonnes worth $1.3 billion; South Korea, 11.2 million tonnes, $892.7 million; and Japan, 7.2 million tonnes, $801.7 million.

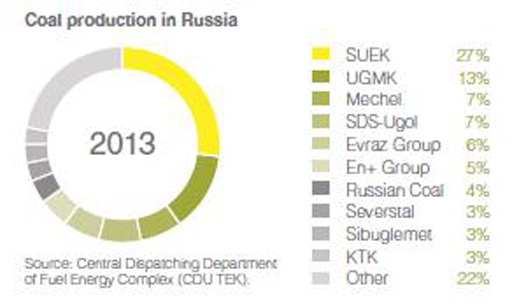

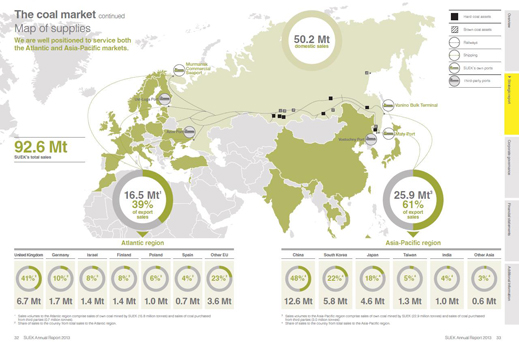

The largest of Russia’s steam coal exporters are SUEK, owned by Andrei Melnichenko (lower left), and Kuzbassrazrezugol (KRU/UGMK), owned by Iskander Makhmudov (right). SUEK’s principal ports for coal shipments westward are Murmansk on the Barents Sea, and Ust-Luga on the Gulf of Finland; for eastward shipments SUEK uses Vanino and Maly-Vostochny, on the Sea of Japan. KRU/UGMK has just consolidated its control of Vostochny.

Melnichenko has been unable to raise capital or set a price for SUEK shares by making an initial public offering (IPO) in London. Makhmudov has not made the attempt at an equity issue in western markets. Both are now suffering from the revenue impact of falling coal prices, and from the liquidity restrictions and rising interest rates of the Russian banks on which they depend.

The Moody’s rating agency has not re-rated SUEK in the year since it issued its October 2013 report. That warned of “SUEK’s high level of dependency on external financing, primarily due to the volatile seasonal nature of the company’s working capital needs, sizable debt service burden and capex; and … the risks related to the company’s concentrated ownership structure including related-party transactions and/or pro-shareholder finance policies.”

Late last month Moody’s downgraded Makhmudov’s company, warning that “coal prices will remain under pressure over the next 12 months, offsetting the benefits of ruble devaluation.” Moody’s also warned that KRU is vulnerable to “low transparency in the transactions with related parties”. As in the SUEK report, that’s Moody’s lingo for cash-stripping by the control shareholder.

The largest of the Russian coking coal exporters are Mechel, which used to be controlled by Igor Zyuzin and is now in the process of takeover by VTB Bank; and Raspadskaya, now a unit of the Evraz group owned by Roman Abramovich.

Because of the size of Russia’s steel industry, most Russian coking coal is consumed at home. Gas, hydropower, and nuclear energy are more favoured for electricity generation, so larger volumes of steam coal are exported. SUEK draws the map of its coal sales like this:

Source: SUEK, Annual Report 2013, page 33

Still, the coal export trade is of far less importance for Russia than it is to Australia, whose steel production is inconsequential. By contrast, Australia exported to China 100 million tonnes of coal in 2013, worth A$9.1 billion. Iron-ore was Australia’s largest export to China, worth last year A$94.7 billion.

Coal came second. The falling price of coal in global trade has pushed a third of Australian coalmines to the brink of insolvency, and thousands of jobs have already been cut. The Chinese import tax is reckoned by Australian analysts likely to cost $350 million per annum in coal revenues, and 20 million tonnes of coal shipments

Last year, China imported 327.1 million tonnes of coal, which accounted for 10% of the coal consumed domestically. The remainder was produced by Chinese mines.

Although the Chinese government has said for months that it was considering import taxes and quotas to relieve the pressure on its high-cost, loss-making domestic mines, Australian media report the Chinese move as a “surprise”, a “shock decision”, “bombshell”, “discrimination”, “diplomatic insult”, “disrespect”, “economic threat”, “disaster”, and a “pair of hand grenades.”

The Australian prime minister, Tony Abbott (lead image, right), reacted violently, “slamming” the import tax, according to one newspaper, claiming it was a “surprise” to him, and promising to “fight” the Chinese.

A source close to BHP Billiton, Australia’s dominant mining company and its largest coal producer, said privately the new Chinese coal tax is “is typical of China’s approach to self-interest in business. In the end, they all play the same game, which is about protecting their own turf.

For them it is not about politics as much as it is about business. And they are not subtle about it – witness them doing something that flies in the face of their free trade agreement negotiations. They just don’t care and they don’t care who knows it. It has been like this since they found their economic power.”

Publicly, BHP acknowledged the Chinese tax is “an added and unwelcome weight on the mind of BHP Billiton’s boss, Andrew McKenzie (right), an ardent free-trader”. The Chinese analysis is that free trade, as defined by BHP, means price rigging.

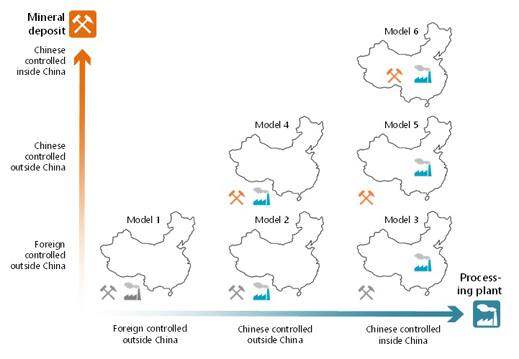

A recent study commissioned by the Global Mining Association of China (GMAC) forecasts a strategic shift in Chinese mining and resource pricing policy, in order to eliminate the dominance of foreign pricemakers like the Australians and Australia-linked coalminers – BHP, Rio Tinto, and Glencore Xstrata. “Before the last resources boom,” report GMAC consultants Nigel Rockcliffe and Jim Marron, “China was largely a price taker and content to be so.

Prices were reasonable; and besides, only manufacturing industry could absorb the millions of displaced workers that were coming off the land—something mining could never do. Then came the resources boom and the price shocks that accompanied it. Chinese buyers were caught off-guard. If they wanted price stability they had to turn from being price takers to price makers. And to do that they had to become miners and ore processors themselves.”

In coal, the GMAC study forecasts, China is not simply intending short-term price and job support for high-cost mines. “Geographically stranded deposits can be made viable with improved transport, and low-grade deposits made viable with improved processing. China has vast reserves of both. With ingenuity and effort they can be, and are being, utilised…New rail capacity is planned so as to open up coal deposits in western China, which, as future open-pit mines, are inherently safer than the underground mines they replace.

Whether this results in coal going east or generating capacity locating west is an open question. Existing electricity generators and consumers are mostly in the east. But nation-building and environmental reasons could favour building new capacity in the west. Alternatively there could be more ‘coal by wire’. Although only a fraction of Chinese coal consumption is affected, it will have a big impact on the market for globally traded coal.”

The GMAC report says the direction in Chinese strategy is inevitable and also irreversible — from Model 1, on which the Australian exporters depend, to Models 4, 5 and 6, in which the Chinese and Russian state banks will play an expanding role to finance new coal sources.

Source: Global Mining Association of China (GMAC)

For analysis of the comparable Chinese strategic shift in iron-ore, and mining plans to replace Australia with new mines in west Africa, read the Sundance story.

Anticipating last week’s duty announcement Russian coalminers have been lobbying officials in the federal ministries of Energy and Trade to ensure that the Chinese trade action will not penalize Russian coal. Russian trade officials in Shanghai and Beijing declined to comment; telephones at the the Russian embassy in Beijing were not functioning for part of this week for what a Shanghai consulate source claims is “remont”.

In Moscow, SUEK said “currently we don’t comment on this topic. At the moment, we have the same terms we have had before.” Evraz said negotiations on the coal tariff must remain a closed book – “public companies cannot afford to comment on government initiatives and the initiatives of regulators.” The new chief executive of Raspadskaya, Sergei Stepanov, said “it is premature to say something about this.”

At the coal industry think-tank, Rusugol, director Anatoliy Skryl said “it is unlikely [the coal duty] will have an influence on the volume of [Russian] coal exports to China.”

Three ministries are involved in the negotiations with the Chinese government – trade, energy, and finance. The Trade Ministry indicated that the coal tax is not being considered as a pure trade issue, but rather as part of the higher-level energy supply relationship between the two governments. Trade referred questions about the tariff to the Energy Ministry. A spokesman at the latter said “there is no official information in the Ministry of Energy [to release], so to comment on it now would be premature.”

The Finance Ministry is responsible for negotiations between the BRICS member states on the establishment of the new BRICS Development Bank, their currency pool, known as the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, and coordination of their positions at the International Monetary Fund.

The official in charge is Deputy Finance Minister Sergei Storchak. He was asked to say if, as coal exporters to China, Russia and South Africa have raised the new coal tariff for coordination at the level of BRICS. Storchak is refusing to say.

By John Helmer, Moscow

http://johnhelmer.net/?p=11707