As leaves turned red, and as San Francisco segued into the smoky autumn of 1950, Edward Nevin lay dying in a hospital bed.

A rare bacteria had entered his urinary tract, made its way through his bloodstream, and clung to his heart — a bacteria that had never been seen in the hospital’s history. Before researchers could hypothesize the bacteria’s root cause, ten more patients were admitted with the same infection. Doctors were baffled: how could have this microbe presented itself?

For nearly thirty years, the incident remained a secret — until Edward Nevin’s grandson set out to bring about justice.

What ensued was a series of terrifying revelations: for two decades, the United States government had intentionally doused 293 populated areas with bacteria. They’d done this with secrecy. They’d done this without informing citizens of potentially dangerous exposure. They’d done this without taking precautions to protect the public’s health and safety, and with no medical follow-up

And it had all started in 1950, with the spraying of San Francisco.

Biological Warfare in the U.S.

Biological warfare, or “germ warfare,” is the “use of biological toxins or infectious agents (bacteria, viruses, and fungi) with the intent to kill or incapacitate humans.” Historically, the United States’ involvement in bacterial weaponry has been driven by competition and paranoia.

In 1918, toward the tail end of World War I, the government briefly experimented with ricin — a deadly, natural plant protein — and the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) was formed to oversee research and development. With the signing of the Geneva Protocol in 1925 (which prohibited the use of biological and chemical weapons in international warfare), the U.S. government’s interest waned: until the 1940s, biological weapons were largely considered impractical.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, the United States changed its mind.

In 1942, President Roosevelt signed into action the first biological warfare program; backed by the National Academy of Sciences, the initiative sought to develop biological weapons and explore vulnerability of the U.S. to such attacks. A government body — the War Research Service (WRS) — was created to oversee these activities, and George W Merck (of the Merck Pharmaceutical Company) was appointed to leadership. At his team’s directive, Fort Detrick, the United States’ biological warfare “headquarters,” was constructed in the small town of of Frederick, Maryland.

The facility then embarked on top secret plan to stage open-air “biological warfare tests” using the unsuspecting American public.

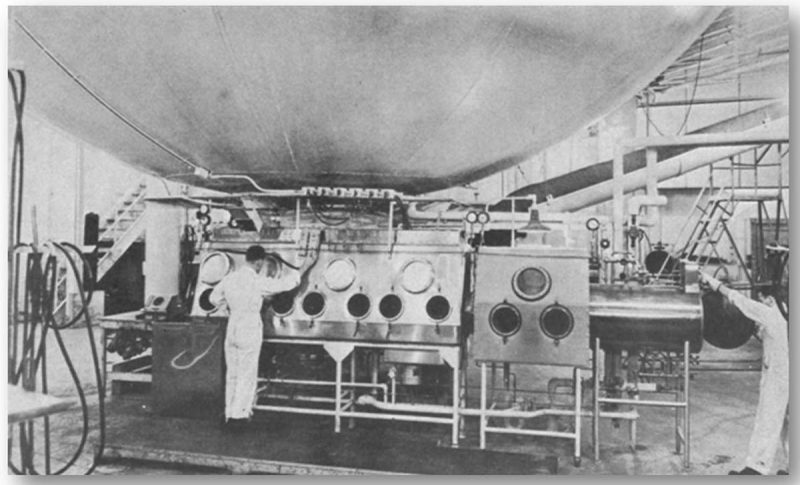

Technicians test a bacteria at Fort Detrick (c.1940s)

By the the end of World War II, the government had amassed a massive arsenal of biological weapons (using anthrax and other various bacteria) — all under the “strictest secrecy.” Soon, justification for continuing the research shifted to the “need for national defense.”

“Work in this field cannot be ignored in a time of peace,” Merck warned officials. “It must be continued on a sufficient scale to provide an adequate defense.”

The government agreed. Under the command of University of Wisconsin professor and bacteriologist Ira Baldwin, A Committee on Biological Warfare was established in 1948. When a subsequent report determined that the United States was “particularly susceptible” to attacks, a series of “open air tests” were ordered.

The purpose of these efforts? To simulate the effects of a realistic biological warfare attack. With a plan in place, a task force was sent to unleash bacteria on San Francisco.

San Francisco’s Bacteria Fiasco

A confidential government report written in 1951 — “Special Report No. 142: Biological Warfare Trials at San Francisco, California, 20-27 September 1950” — maps out the details of the city’s top-secret bacteria bombing.

Through the tests, officials sought to accomplish three objectives: to study the “offensive possibilities of attacking a seaport city with a biological warfare aerosol,” to highlight the vulnerability of the country’s defense against such attacks, and to gain data on how bacteria affected a population.

Nowhere in the report was the welfare of San Franciscans mentioned; the tests proceeded without knowledge or consent from the public.

On the 20th, just three days after the 49ers made their NFL debut, the U.S. Army was deployed to San Francisco and began secretly showering the city with bacteria.

Over a course of eight days, a ship puttered along the shoreline of the bay, releasing massive clouds of two different pathogens — both of which were supposedly non-pathogenic, yet “realistic simulants that might be used in an attack.”

In total, six “experimental warfare attacks” were carried out: four with Bacillus globigii, and two with Serratia marcescens.

Serratia marcescens, known for its blood-red coloration, is one of two bacterias sprayed over San Francisco in 1950

The Army blasted these chemicals in 30-minute spurts, producing huge clouds up to two miles in length, then proceeded to collect and assess dozens of samples a various collection spots across the city.

As noted in the report, various aspects of each of the six tests were scrupulously monitored — the time, the temperature, the wind speed, the humidity — but the most important factor seemed to be brushed over: the well-being of the people being sprayed.

The samples collected yielded counts that gave some indication of how much bacteria was being inhaled. According to Leonard J. Cole, author of the biological warfare book Clouds of Secrecy, it was quite a bit:

“Nearly all of San Francisco received 500 particle minutes per liter. In other words, nearly every one of the 800,000 people in San Francisco exposed to the cloud at normal breathing rate (10 liters per minute) inhaled 5000 or more particles per minute during the several hours that they remained airborne.”

“Since the army’s bacteria ‘presented similar dosage patterns,’” he continues, “San Francisco residents were inhaling millions of the bacteria and particles every day during the week of the testing.” San Francisco residents’ safety was wholly brushed over in the report, which promptly concluded “it’s entirely feasible to attack a seaport city with [biological warfare] aerosol.”

The Death of Edward Nevin

A month prior to the Army’s tests, a 75-year-old man named Edward Nevin checked into a San Francisco hospital to undergo a prostate gland surgery. The procedure went well, and after a month in the facility, he was on his way to recovery.

Then, on September 29, two days after the Army’s tests, Nevin fell contracted a urinary tract infection and fell gravely ill. When the man’s urine culture came back, it contained Serratia marcescens — a bacteria that had not once been documented in the hospital’s long history.

In mid-October, the bacteria spread to Nevin’s heart, and he died.

Over the next six months, 10 more patients were admitted with infections caused by Serratia marcescens (all of whom later recovered after long, painful hospital stays).

Like the rest of San Francisco’s citizens, the hospital’s doctors were unaware that the government had just clandestinely sprayed the city with Serratia marcescens. A panic ensued at the hospital, as researchers frantically struggled to determine how the bacteria infected these people.

The following year, a team of Stanford University researchers dug into the case; led by Dr. Richard Wheat, they published an article in the American Medical Association’s Archives of Internal Medicine exploring the facts: 11 patients infected over 6 months, aged 29-78, all with urinary tract infections caused by Serratia marcescens.

Despite the best efforts of some of the nation’s leading scientists, no source could be identified. Historically, Serratia marcescens had no record in San Francisco — or California, for that matter.

The medical paper did not go unnoticed: when the government read it and realized that they’d caused a bacterial outbreak, they reeled to cover their tracks.

In August 1952, a secret, four-person investigation was ordered by Fort Detrick commander, General William Creasy to reassess the pathogenic nature of Serratia marcescens. In a two-page report, the investigators admitted that the bacteria was NOT an “ideal simulant,” and mused that the likelihood it had killed Nevin was considerable.

Despite this, they proceeded to justify its continued use in biological tests:

“On the basis of our study, we conclude that Serratia marcescens is so rarely a cause of illness, and the illness resulting is predominantly so trivial, that its use as a simulant should be continued, even over populated areas.”

Throughout the report, investigators showed little remorse for the infected civilians. General Creasy was equally unphased: in a follow-up with Army officials, he promised to consult with the U.S. Public Health Service regarding the safety of Serratia marcescens — but he never did.

And all the while, the public remained completely in the dark about what was going on.

Edward Nevin’s Grandson Fights for Justice

For 25 years, the government’s involvement in biological warfare testing — and its use of civilians as unwitting guinea pigs — remained top-secret. It’s a secret that likely would’ve gone on indefinitely if not for the efforts of a savvy Newsweek reporter named Drew Fetherston.

In November 1976, Fetherston exposed a number of biological tests performed in major cities by the Army and the CIA. Using his research, the San Francisco Chronicle uncovered the bacteria spraying that had occurred in its streets in 1950.

A sketch of Edward Nevin III — Edward Nevin’s grandson

Edward Nevin III, a young lawyer in San Francisco, was waiting for a train in nearby Berkeley when he read the news. When he skimmed the name of the man who’d died from the bacteria — Edward Nevin — he reeled in shock. Good heavens, he muttered, that’s my grandfather!

Growing up, he’d always been told that his father’s father had died from kidney disease; now that he knew the bitter truth, he felt a need to exact revenge in the form of justice.

Nevin wrote the government, demanding access to case’s related documents; his request was denied. Though the Freedom of Information Act had just been enacted, the government maintained that all files were classified — despite the fact the the media had already exposed the incident.

In turn, Nevin sued the government to the tune of $11 million.

“Our motive [is] to obtain information,” he told a group of reporters who’d asked about the high amount, “would you fellows have paid attention if the claim were for only a few thousand?”

The government tried to dismiss the case on the grounds that they were immune from lawsuits involving “basic policy,” but the request was denied. Samuel Conti, a federal judge, was appointed to preside over the trial, and a date was set for mid-1977.

In light of this news, the government decided it was best to relinquish some of its information. In February 1977, an extensive history — “U.S. Army Activity in the U.S. Biological Warfare Program, 1942-1977” — was released, chronicling the country’s involvement in open-air testing for the first time in history. (Click the image below to view the document in its entirety):

From March to May of 1977, a series of hearings commenced in the Senate’s subcommittee on Health and Scientific Research. Medical experts, military leaders, and politicians ferociously debated whether or not Serratia marcescens — the bacteria that killed Nevin — was harmful. George H. Connell, the assistant to the director of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), was especially vocal about its dangers:

“There is no such thing as a microorganism that cannot cause trouble. If you get the right concentration at the right place, at the right time, and in the right person, something is going to happen.”

“An increase in the number of Serratia marcescens,” added an unnamed microbiology professor, “can almost certainly cause disease in a healthy person…and serious disease in sick people.”

A copy of the full hearing transcript (all 300 pages) can be accessed by clicking the image below:

Meanwhile, Nevin III’s trial was postponed or rescheduled a half dozen times from 1977-1980. By the time a trial was set in stone for March 16, 1981, he’d already spent some $60,000 on legal fees, and was mentally and emotionally drained.

Nonetheless, he found solace in the case’s [stipulations]: to win, all he’d have to do is show that there was a “probability” — or greater than a 50% chance — that the Army’s germs were responsible for his grandfather’s demise.

And as a lawyer, he’d have the opportunity to defend his own family in court.

As the trial began, the evidence seemed to be overwhelmingly in Nevin III’s favor: on September 26th and 27th, the government had sprayed the city with Serratia marcescens; on September 29th, Serratia marcescens showed up in his grandfather’s system — and directly led to his death.

“We’ve been nothing but loyal to this country,” Nevin told the Judge Conti in his opening statement. “and we feel betrayed.”

His argument was threefold: the bacteria sprayed by the government directly caused his grandfather’s death; the Army used Serratia marcescens despite inadequate testing; and, since they’d sprayed it without consent, it had been “an act of negligence.” He questioned the legality of these actions:

“On what basis of law does the U.S. government of the United States justify the dispersion of a large collection of bacteria over the civilian population in an experiment…without informed consent?”

John Kern, the sharp, respected attorney representing the government, denied all of these allegations. The Serratia marcescens that killed Nevin and the Serratia marcescens released by the Army were two entirely different strains, he maintained; it was mere coincidence that the hospital had an outbreak around the same time.

Incredibly, Kern also attested that the Army needed no permission to spray the public without consent or knowledge.

The Federal Torts Claims Act, established in 1946, gave the public the right to sue the Federal government — but it came with limitations. Among them, a vaguely-worded “discretionary function” made the feds immune to suits in which they were “performing appropriately under policy.” The dousing of civilians in bacteria, contended Kern, qualified as such.

Kern then launched into a theatrical denial of Serratia marcescens’ harmful effects. “Every atom in this pen could decide right now to rise up about six inches and turn around 180 degrees,” he emphatically stated, with his pen thrusted in the air.

That, he concluded, would be about as likely to happen as the bacteria killing someone. He continued, citing a series of Fort Detrick tests in the 1940s in which “volunteers” were exposed to millions of Serratia marcescens organisms and suffered only “some coughing, redness of the eye, and a fever,” with all symptoms subsiding after a few days.

One of Kern’s witnesses, a doctor for the biological warfare unit at Fort Detrick, agreed. In possibly the most callous statement of the day, he looked Nevin III in the eyes, and delivered his opinion: “The strain [wasn’t] pathogenic,” he said, “[and] I would still spray SF again today.”

Dr. Wheat, the Stanford physician who’d investigated Nevin’s death in 1951, testified to a different tune.

“No similar organisms had ever been isolated in the hospital laboratory…then over a relatively short period of time, there were a number of cases,” he told the judge. “It’s very difficult for me to escape the conclusion that there is at least some probability, some causal effect [that the cases are related].”

Debates on the bacteria’s safety and the cause of Nevin’s death continued in this way for several hours, each side presenting a slew of medical “experts.” The government’s legal team maintained that the odds of Nevin’s death being linked to the Army’s bacteria spray were “one in a hundred;” Nevin III’s witnesses held the belief that the events were inseparably connected.

General William Creasy in uniform

When it came time to cross-examine military officials, the case suddenly took a jarring turn.

As General William Creasy, commander of the United States’ biological warfare unit, stepped to the stand, it became clear that presiding judge Conti was leaning toward the defense of the military. “When the government trotted out a witness in uniform,” noted one San Francisco Examiner court reporter, “it was all over.” After telling Nevin III that he was “wasting [his] time,” the General proceeded to defend the ethics of spraying people without their knowledge:

“I would find it completely impossible to conduct such a test trying to obtain informed consent. I could not have hoped to prevent panic in the uninformed world in which we live in telling them that we were going to spread non-pathogenic particles over their community; 99 percent of the people wouldn’t know what pathogenic meant.”

During the cross-examination, Judge Conti continually denied Nevin III’s reasoning, and even berated him for his lack of respect toward military officials. After several interruptions, Judge Conti altogether halted the questioning and called a recess. Out in the hallway, a belligerent General Creasy unsuccessfully challenged Nevin III to a fistfight.

Nevin III’s legal opponents were simply too powerful: he was swimming upstream and flailing.

When Judge Conti’s verdict was handed down on May 20, 1981, it surprised no one: the case was ruled in favor of the government.

The Army had been entitled to spray the population without consent, concluded Conti, under the “discretionary function exception” in the Federal Tort Claims Act. Despite a lack of convincing evidence, Conti also declared that the Army had skillfully chosen its bacteria — and that it was not, in fact, harmless.

For Nevin III, whose grandfather had died from the organisms, this was not easy to swallow. He appealed, but the U.S. Court of Appeals did not overturn the verdict. He appealed again — this time to the Supreme Court — and received a similar response.

For Nevin III, justice was not served.

Aftermath

San Francisco’s incident was just one of 293 bacterial attacks staged by the United States government between 1950 and 1969. It was neither the most heinous, nor the deadliest.

In 1955, as an “experiment,” the CIA sprayed whooping cough bacteria over Tampa Bay, Florida. Whooping cough cases in the area subsequently increased from 339 and one death in 1954, to 1,080 and 12 deaths in 1955 — but no hard evidence has ever surfaced linking the two incidents.

In an infamous 1966 test, federal agents crushed light bulbs containing trillions of bacteria on the New York Subway, exposing thousands of rush hour commuters; the government never followed up to see how many people fell ill.

Before a crowd at Fort Detrick in 1969, Richard Nixon terminated the offensive use of biological weapons in the United States, effectively ending open-air testing.

It wouldn’t be until 1977 that the public learned any of this was even going on — and even then, the U.S. government never admitted its fault, or seemed to show any indication of remorse for its actions.

***

Serratia marcescens, the bacteria sprayed over San Francisco, has since been declared hazardous. “It can cause serious life-threatening illness,” wrote the FDA in 2005, “especially in patients with compromised immune systems.” Much other medical literature contends the same.

Today, Edward Nevin III is a practicing medical malpractice and personal injury lawyer in Petaluma, California. Though he lost the case in 1981, he succeeded in bringing to light many government actions that had previously been shrouded in secrecy.

“At least we are all aware of what can happen, even in this country,” Nevin Jr. said, shortly after the trial. “I just hope the story won’t be forgotten.”

[The article was originally published by Oct 30, 2014. However, in the wake of Wuhan novel coronavirus, this article we believe is worthy to be republished.]

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.

To learn more about other biological warfare testing in the U.S., refer to Leonard J. Cole’s incredibly well-researched history, Clouds of Secrecy.

First published by Priceconomics

The 21st Century

How the U.S. Government Tested Biological Warfare on America