Peter Hallward Untangles the Truth about Haiti from a Web of Lies

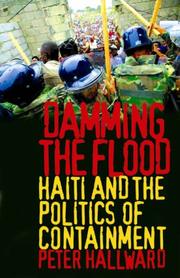

In Damming the Flood: Haiti, Aristide, and the Politics of Containment, Peter Hallward meticulously explains how, on February 29 of 2004, the U.S. managed to “topple one of the most popular governments in Latin America but it managed to topple it in a manner that wasn’t widely criticized or even recognized as a coup at all.”

Imperial powers do not reinvent the wheel when it comes to undermining democracy in poor countries. Hallward identifies valuable lessons for people who wish to limit the damage that powerful countries inflict on the weak.

The narrative he presents is not complicated, but to present it he must expose countless lies and half truths and brilliantly explore many simple questions that corporate journalists invariably failed to ask.

The story the corporate press and even some alternative media presented to the world, when it was coherent at all, is roughly what follows.

Aristide was elected Haiti’s president in 1990 in the country’s first free and fair election. He was overthrown in 1991 by the Haiti’s army at the behest of Haiti’s elite who feared that he may lift the poor out of poverty and powerlessness.

The US, despite some misgivings, restored him to power in 1994 after economic sanctions failed to budge the military junta that replaced him. He stood aside while his close ally, Rene Preval, occupied the presidency for several years. In 2000 Aristide was brought to power through rigged elections.

By the end of 2003 Aristide had lost popular support and important allies due to corruption and violence. He could only keep power because he had armed gangs in the slums. In February of 2004, faced not only with a broad-based political opposition, but by armed rebels and gangs who had turned against him, Aristide resigned and asked the US to fly him to safety as the rebels were about to overrun the capital.

Hallward shows that hardly anything about the widely accepted narrative above is true.

The US was behind the first coup that ousted Aristide in 1991 and supplied the junta through a selectively porous embargo. It restored Aristide in 1994 because the political price of playing along with the junta had become exorbitant.

After he was restored, the US made sure that Haiti’s security forces were infiltrated by henchmen of the military regime and leaned on Aristide to implement unpopular economic policies — far beyond what he had agreed to as a condition for being restored. He resisted US pressure for further concessions on economic policy and disbanded the Haitian army over strong US objections.

In response, the US spent 70 million dollars between 1994 and 2002 directly on strengthening Aristide’s political opponents. Over these years many of Aristide’s allies among the “cosmopolitan elite,” as Hallwards calls them, became bitter enemies.

Often their resentment stemmed from being passed over by Aristide for jobs or political endorsement in favor of grassroots activists from the Lavalas movement. Some defectors from Aristide’s camp, like Evans Paul, had impressive track records in the fight against pre-1990 dictatorships and against the 1991 coup, but by 2000 most had joined a coalition with the far Right (known as Democratic Convergence) which was cobbled together with US money.

Invariably, these former Aristide allies lost almost all popular support after defecting to the US camp. However they were well connected with foreign NGOs and the international press. The elections of 2000 were not only free and fair, but the results were completely in line with what secret US commissioned polls had predicted. Aristide’s opponents were trounced but successfully sold the lie that the 2000 elections were fraudulent.

The US (joined by the EU and Canada) blocked hundreds of millions of aid from Aristide’s government. An unsuccessful coup attempt by far-right paramilitaries took place in 2001. Other deadly attacks on Lavalas partisans took place during Aristide’s second term but went largely unnoticed by the international press and NGOs. In contrast, reprisals on Aristide’s opponents were widely reported.

By late February of 2004, both the political and armed oppositions were in danger of being exposed as frauds. US destabilization efforts, though successful in many ways, had failed to produce an electable opposition to Aristide and his Famni Lavalas party.

The rebels, whose collusion with the political opposition was becoming difficult for the corporate press to ignore, were in no position to take Port-au-Prince. Hence, the US moved in to complete the coup themselves (with crucial assistance from France and Canada) and not through Haitian proxies as they had in 1991.

The kind of detailed internal record that exists for U.S.-backed coups in Chile and Argentina during the 1970s is not yet available in the case of Haiti. Though important fragments have been uncovered by researchers like Anthony Fenton, Yves Engler, Isabel Macdonald, and Jeb Sprague, Peter Hallward makes his case by carefully gathering uncontroversial facts (like the presidential election results of 2006 in which the pro-coup politicians were crushed) and then applying logic and common sense.

Hallward might have gone into more detail about how Aristide kept most Haitians on his side in the face of such a relentless onslaught from such powerful enemies. The social programs Aristide’s government implemented and the inclusive and participatory nature of the Famni Lavalas Party were certainly mentioned in the book, but they should have been elaborated on. There are crucial lessons to be learned there for people’s movements around the world.

Hallward is accurate in describing his book as “an exercise in anti-demonization, not deification.” He wrote that if Aristide “shares some of the responsibility for the debacle of 2004 it is because it occasionally failed to act with the sort of vigor and determination its most vulnerable supporters were entitled to expect.”

Hallward says a certain amount of complacency took hold in Fanmni Lavalas due to its popularity, and that it was sometimes slow to recognize enemies and opportunists within its ranks, but Hallward should have placed more emphasis on his concluding point that the renewal of Haitian democracy “will require the renewal of emancipatory politics within the imperial nations themselves.”

It is mainly we, within the imperial nations, who need to do the soul searching and analysis of what we should have done better. Aristide hinted at this crucial point in his interview with Hallward:

“The real problem isn’t really a Haitian one, it isn’t located within Haiti. It is a problem for Haiti that is located outside Haiti!”

By Joe Emersberger

This article was originally published at MR Zine –