I’ve been hearing about neoliberalism for a long time now and never could make much sense of it. It turns out the story we tell about neoliberalism is as contradictory as neoliberalism itself.

Two currents within the critique of neoliberalism offer different analyses of the current economy and suggest different strategies for dealing with the gross exploitation, wealth inequality, climate destruction and dictatorial governance of the modern corporate order.

These opposing currents are not just different schools of thought represented by divergent thinkers. Rather they appear as contradictions within the critiques of neoliberalism leveled by some of the most influential writers on the subject.

These different interpretations are often the result of focus. Look at neoliberal doctrine and intellectuals and the free market comes to the fore. Look at the history and practice of the largest corporations and the most powerful political actors and corporate power takes center stage.

The most influential strain of thought places “free market fundamentalism” (FMF) at the center of a critical analysis of neoliberalism. The term was coined by Nobel Prize winner and former chief economist of the World Bank itself – Joseph Stigliz.

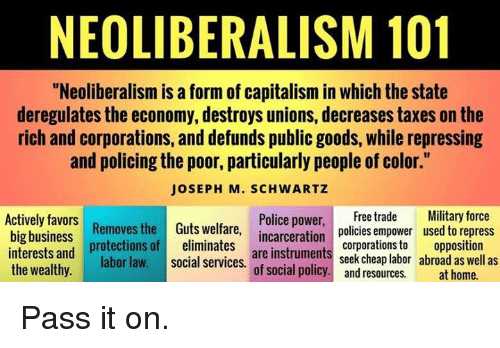

FMF is usually how neoliberalism is understood by progressives and conservatives alike. In this view, an unregulated free market is the culprit and the oft cited formula — de-regulation, austerity, privatization, tax cuts — is the means used to undermine the public commons.

David Harvey’s, A Brief History of Neoliberalism, is perhaps the single most influential book and the author begins with the free market. Harvey sets it up like this:

And it is with this doctrine…that I am here primarily concerned. Neoliberalism is…a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human wellbeing can be best advanced by liberating individual entreprenaurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets and free trade. The role of the state is to create… an institutional framework appropriate to such practices. [1]

Not a mention of the massive modern corporation just those 19th century individuals and institutions that are the stock characters of FMF. But to be fair, Harvey moves on to the “paradox:” neoliberalism is a political project that needs state power.

This creates the paradox of intense state interventions and government by elites and ‘experts’ in a world where the state is supposed not to be interventionist. [2]

The idea that the “free market” is an accurate description of reality or a good basis for strategy has worn thin. What started as the less influential reading of the neoliberal critique is gaining ground.

The market economy and the state changed over time into something quite different — something we might call Corporate Power. And that is a far cry from a fundamentalist return of the liberal free market of the 19th Century.

Instead, we confront a new form of capitalist order: the merger between the biggest corporations and the state. The corporate power dominates nations by hollowing out and commandeering the institutions that were supposed to represent people. Economic decisions are made behind closed doors at the Treasury Department or Federal Reserve where bankers rule and regular citizens dare not go.

The same power operates on the global stage through international institutions and regulatory bodies that do not even pretend to be democratic such as WTO, IMF, and World Bank. Corporate power tends toward fascism by destroying democracy and imposing austerity — the very conditions that give fascism mass appeal.

The national and global institutions that have been so essential to the creation of the neoliberal order provide rich evidence that we can no longer tell where governments end and corporations begin.

The Shock Doctrine, by Naomi Klein, remains very influential and touches on both critiques. But the closer the author got to the military-industrial complex and war —the core functions of the state — the clearer the corporate power argument became.

[T]he stories about corruption and revolving doors leave a false impression. They imply that there is still a clear line between the state and the complex, when in fact that line disappears long ago. The innovation the Bush years lies not in how quickly politicians move from one world to the other but in how many feel entitled to occupy worlds simultaneously ….They embody the ultimate fulfillment of the corporatist mission: a total merger of political and corporate elites in the name of security, with the state playing the role of chair of the business guild—as well as the largest source of business opportunities…[3]

Exactly. But, FMF and “a total merger of political and corporate elites” are completely at odds with one another. Another widely read author puts it this way:

“There is a profound irony here: In that neoliberalism was supposed the get the state out of the way but it requires intense state involvement in order to function.” — George Monbiot

If the contending ideas of FMF and corporate power were strictly academic it would not matter so much but we will not develop a successful strategy to counter corporate power without knowing what the actual material conditions are.

While FMF obscures the current state of our economy, corporate power helps us to see through the seemingly ironic fact that the so-called free market relies upon regular government interventions and support.

We’re dealing with irony or paradox only in as much as we’re dealing with modern mythology. Myths endure because their stories resolve contradictions that logic, reason and facts cannot.

Let’s Stop Repeating the Bosses’ Propaganda.

The emphasis on FMF has unwittingly contributed to the deeply rooted mythic aura of free markets. Adam Smith, the first philosopher of markets, had to resort to an unexplainable “Invisible Hand” to argue that capitalism was good for everyone.

This faith lives on in the neoliberal portrayal of global markets as omnipotent, unknowable forces that work in mysterious ways. If that sounds like the god of capital — it is.

But we need to come to terms with the fact that the free markets’ mythical and mystical nature is precisely why it has such a grip on the popular imagination — and on our own. If we believe free markets actually exist then even our critiques are offerings to its god-like power. When we say “free market” it works like an incantation summoning a complete worldview into being.

For example, critiques of the free market too often internalize the neoliberal claim that it’s the natural form of human exchange and production. According to this view, the market exists independently somewhere “out there” in human nature or society.

Lack of regulation allows market freedom to run to its logical or natural conclusion even if it’s prone to excess and crisis. So the role of the regulatory state, in this argument, is to control the natural freedom and drive of the market actors.

But corporate power imposes its ideology by force and often violence. It exploits people in accordance with law. It plunders resources and poisons water without consequence.

This is not freedom. It is dominance and supremacy which puts us on a path to environmental destruction, oligarchy — maybe even fascism. If your “freedom” is my exploitation then you are my master, I your slave, but neither of us are free. Corporate power is the opposite of freedom.

Market ideology has always hidden authority, power and responsibility behind a screen of individual freedom and anonymous actions.

If the free market is the outcome of millions of interactions between free individuals, and no one is really in charge, well, what is wrong with that? Plenty, starting with the fact that this utopian ideal in no way describes the dominant form of capitalism in our time — if ever.

And if we believe there is a free market then how do we deal with the widely held belief in the morality of the market? Millions still believe the economy to be moral because it works like a true and transparent regulator of merit.

The good rise, the weak fall. The Protestant Work Ethic remains the most powerful spiritual belief shoring up capitalism. If we accept the market as the actual basis of our economy then how can we oppose the idea that hard work is in fact justly rewarded?

No wonder millions of American workers don’t embrace or cannot understand the neoliberal critique: who can really oppose nature — or society, or freedom, or morality? But unlike the “free market,” which everyday people often associate with small entrepreneurs and mom and pop shopkeepers, millions of people can oppose corporate power.

By shifting to the idea of corporate power we can make claims in keeping with day-to-day experience of the working class: work is not about freedom but instead compulsion and coercion; the economy is not based on merit but rigged to favor the powerful. The common understanding that the economy is rigged has outpaced the viewpoints offered and believed by many progressives. The people are leading, let’s catch up.

There is no market in pure or natural form. Instead market forces and political power interact to create the economy, in other words we have a political-economy. Corporations were born political actors. And the corporate power, not the free market, is the only form of capitalism worth overthrowing.

Does History Matter?

The irony or paradox at the heart of the FMF critique is really a failure to give history its due.

When societies reach this kind of end stage, the language they use to describe their own economic and political and social and cultural reality bears no relation to that reality…. The language of free market laissez-faire capitalism is what they feed business students and the wider public but it is an ideology that bears absolutely no resemblance to that reality…..In a free market society all those companies like Goldman-Sachs would have gone into bankruptcy but we do not live in so-called free market… Chris Hedges

So where did the free market go? The modern corporation itself overcame the many inefficiencies of 19th century free market capitalism; it replaced “cutthroat competition” with the coordination, cooperation and economies of scale to destroy smaller firms or consolidate them into monopolies.

Over time competition evolved into monopoly power. Individual entrepreneurs were dwarfed by concentrated wealth’s immense power. The free market was replaced with a public/private mix where both public policy and market signals regulated and promoted economic activity. [4]

This long historical shift away from free markets and toward corporate power has left such a clear trail of evidence it’s a wonder it’s not self evident. How else can we interpret the corporatization of war and the military and the billions in direct and indirect subsidies to corporations?

Government shelters banks, guaranteeing loans and mortgages while bailing out stupid investors. [5] Wealth is redistributed to the top though massive tax breaks and cuts to social programs.

Legally enforced starvation wages push workers to public assistance ultimately subsidizing their bosses. Tax codes encourage the rich to shelter trillions in tax havens while the unrepresented masses make up the difference.

Federal programs like “quantitative easing” pumps free money into the financial system. The risk and losses from environmental destruction are for us to reckon with while the rule of law has been suspended for corporate criminals of all kinds.

Major economic decisions have largely migrated from national governments to even more dictatorial global bodies. The IMF, WTO and World Bank do the bidding of the largest corporations that are the foundation of the US imperial alliance.

But this history holds opportunity as well. This is what it’s come to:

Private forms of corporate ownership are “simply a legal fiction.”* The economic requirements of the modern corporation no longer justify its completely private control, for “when we see property as the creature of the state, the private sphere no longer looks so private.”**….In this regard, property reassumed the form it took at the dawn of the capitalist era when “the concept of property apart from government was meaningless.”*** [6]

By merging with the state the largest corporations have turned themselves into a new form of social and public property. It’s up to us to take what is ours.

Everything lives and everything dies. The most important lesson from the history of capitalism is this: It has sown the seeds of its own destruction.

The critique of neoliberalism as FMF unconsciously promotes what it intends to criticize precisely because it imagines the current system as essentially the same system that existed in the 19th Century. This critique smuggles in the lack of historical thinking that is so essential to maintaining dominant culture in the US.

FMF is a form of American exceptionalism. If the current economy is essentially the same as more than a century ago, then it is truly exceptional and outside of history — just like America itself.

Isn’t it? Does capitalism have a history or doesn’t it? In general, the lack of historical consciousness lies at the heart of American exceptionalism. It hobbles our capacity to think and act. This denial of history is the masters’ mythology, not ours.

Corporate power is not eternal but historical. It too shall pass — but only if we make it so.

Richard MOSER

First published by counterpunch.org

The 21st Century

Notes

[1] Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism, p. 2.

[2] Harvey, p.69 Over time Harvey has tended to highlight the political not doctrinal aspects. See Neoliberalism as a Political Project

[3] Naomi Klein, Shock Doctrine, p. 398-399.

[4] I borrow the idea of a public/private mix from the work of the under-appreciated New Left historian Martin Sklar see: United States as a Developing Country. For more on Sklar look here or Jim Livingston’s essay here.

[5] Nomi Prins All The Presidents Bankers, see p. 372-375 for an account of the so-called Mexican bailout and the role of former Goldman-Sachs executive Robert Rubin in saving the bankers.

[6] Richard Moser, Autoworkers at Lordstown: Workplace Democracy and American Citizenship” in The World the 60s Made, p. 307 *Bell, The Coming of Post-industrial Society, p. 294. **Jennifer Nedelsky, Private Property and the Limits of American Constitutionalism, p. 263. ***Arthur Porter, Job Property Rights, p. l.