The latest Bond flick No Time To Die was certainly a rollercoaster ride of exciting action scenes and great special effects, yet contained more than a quantum of longueurs.

With a running time of 163 minutes it certainly tries the patience and the bladders of its audiences (who I saw popping out of the cinema throughout the film).

Personally, I think 90 minutes is enough for any film, especially since the disappearance of the intermission and ice-cream selling of yore.

In this case, the increased length seems to have been to incorporate backstories of some of the individuals involved.

The effect of this is to attenuate Bond’s appearances in the film, while adding very little to the story (hence the longueurs).

One effect of this narrative style is to put more emphasis on the story of Bond and less on the usual geopolitics and action we associate with Bond films.

Now this is very interesting considering that if one was to ask oneself: which country would be the most likely target and villain of the latest Bond film as a cultural representative of the world’s imperialist and neo-colonial powers? It would have to be: China.

Who’s bad?

Yet there were no Chinese baddies, no stereotyped ‘yellow peril’, no Chinese mad scientists, no Chinese monomaniacal nutter bent on ruling the world.

Why would this be? Could it be something to do with new British geopolitical sensitivities and Brexit anxieties over its current position in the world?

In the past the Russians were usually targeted, as well as the more abstract multinational SPECTRE baddies.

At least during the Cold War (and some time after) there was definitely a cultural reflection of the realities of geopolitics in the James Bond narratives.

Are they keeping one eye on the potential economic and military alliances of the future while keeping the other eye on their current alliances?

Instead what we get is yet another Russian mad scientist with a comically exaggerated Russian accent, lots of SPECTRE goings on, and the monomaniacal nutter ‘Lyutsifer Safin’ (with equally crazy spelling).

Thus we have a caricature of the early Bond films with some ’emotionally deep’ background filling to make up for its lack of relevance to current geopolitics.

Added to this emasculated plotline is the Bond’s 007 replacement with Nomi, his successor – a female black Bond.

Not that there’s anything wrong with a female black Bond, but it does show one of the weaknesses of current identity politics, that her identity as an operative for an imperialist, militarist organisation is more important than her identity as a colonial victim of imperialist, militarist organisations in the past.

The Noname Book Club, for example tweeted the general point that:

“under white domination we consistently celebrate the “first black …” because we’ve been taught that assimilation into white society means safety, upward mobility, liberation. beyond how this can lead to black children idolizing the first black billionaire or war criminal, […] it also individualizes / romanticizes black success. it reduces our desire for collective liberation and makes us hyper focus on white approval.”

There is also a slight ramping up of what I call the ‘theatre of cruelty’ factor – that is the pushing beyond the normal standards of ‘common decency’ that underlies cinema narratives in the public sphere.

In general the depiction of violence and cruelty has been increasing steadily since the 1950s and 1960s, progressively desensitising audiences to basic human norms (another role of action movies like the Bond films).

In this case, a child (Mathilde) is used in the narrative as a human shield but in the end the film does not go so far as to actually hurt her – there are still some limits to what is acceptable in the public’s eyes.

Militarism

However, there seems to be very few limits to the extent to which the British government is creating new and targeted strategies to promote support for the military, for example:

“Armed Forces Day, Uniform to Work Day, Camo Day, National Heroes Day – in the streets, on television, on the web, at sports events, in schools, advertising and fashion – the military presence in civilian life is on the march. The public and ever younger children are being groomed to collude in the increasing militarisation of UK society.”

The role of these forms of militarism has been to encourage people “to see the military, and spying, in positive terms; to think of violent, military solutions as the best way to solve international disagreements; and to ignore peaceful alternatives.”

Children have long been drawn in through comics such as The Boy’s Own Paper, published from 1879 to 1967, and aimed at young and teenage boys.

For example the first volume’s serials included “From Powder Monkey to Admiral, or The Stirring Days of the British Navy” and promoted the British Empire as the peak of civilization.

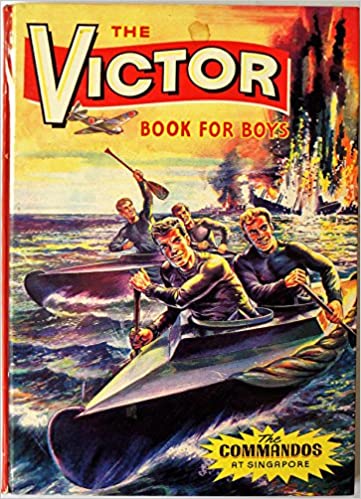

Later comics about World War 2 were founded in the late 1950s and early 1960s, such as War Picture Library (1958), The Victor (1961) and Commando (1961) (which is still in print today) were popular for decades after the war.

According to Rod Driver, these comics:

“had a strong focus on patriotism and heroism. They stereotyped people from enemy countries as cruel or cowardly, and used derogatory terms such as jerries, huns or krauts for German people, eyeties for Italian people, or nips for Japanese people. A generation of children grew up with a very distorted view of the war and people in other countries.”

As for the adults, stereotypes and cruelty are still the stock in trade of culture producers and the James Bond films rejoice in them.

The Victor cover

Recruitment campaigns

The significance of Nomi as a black 007 can be seen in new recruitment advertisements which feature a black female soldier.

Women represent less than 10% of the British Army, so they launched a new female-led recruitment campaign.

According to Imogen Watson, the ‘This is Belonging’ campaign:

“follows the army’s most successful recruitment to date.

Four days after the launch, the record was broken for the highest number of applications received in a single day.

After a month, 141% of the army’s application target was reached.

By March, it had surpassed 100% of its annual recruiting target for soldiers, for the first time in eight years.”

International institutions

In one sense James Bond films depict a reality that despite the many International institutions dedicated to promoting world peace, military build-ups continue apace.

In an article entitled ‘The False Promise of International Institutions’, John J. Mearsheimer writes “that institutions have minimal influence on state behavior, and thus hold little promise for promoting stability in the post-Cold War world.”[p7]

He discusses the differences between the ideas of Realists and Critical Theorists.

The Realists believe that there is an objective and knowable world while the Critical Theorists see “the possibility of endless interpretations of the world before them”, and therefore there is no reason “why a communitarian discourse of peace and harmony cannot supplant the realist discourse of security competition and war”.

However, there is a contradiction in that, for example, Americans who think seriously about foreign policy dislike realism as it clashes with their basic values and how they prefer to think about themselves in the wider world.

Mearsheimer outlines the negative aspects of realism that depict a world of stark and harsh competition, where there is no escape from the evil of power and which treats war as inevitable.

Realism goes against deep-seated beliefs that progress is desirable and “and with time and effort reasonable individuals can solve important social problems.”

One major problem is that while the international system strongly shapes the behavior of states, “states still have considerable freedom of action”.

He gives the example of the failure of the League of Nations to address German and Japanese aggression in the 1930s.

Thus, the role of international institutions may actually be to stave off war until countries feel ready to attack or defend themselves.

What he does not discuss however is the situations where ordinary people rose up to extricate their nations from imperialist wars, such as Ireland in 1916 (“We serve neither King nor Kaiser), and the Peace! Land!

Bread! campaign of the Bolsheviks in 1917.

These campaigns show that while ordinary people are generally considered cannon fodder in times of war, it is possible for future mass movements to transcend the narrow triumphalism and national chauvinism encouraged by recruitment campaigns and blockbuster films.

By Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here.

Published by The 21st Century

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.

[Top photo: Official James Bond 007 Website]