The United States government is accelerating efforts to monitor social media to preempt major anti-government protests in the US, according to scientific research, official government documents, and patent filings reviewed by Motherboard.

The social media posts of American citizens who don’t like President Donald Trump are the focus of the latest US military-funded research. The research, funded by the US Army and co-authored by a researcher based at the West Point Military Academy, is part of a wider effort by the Trump administration to consolidate the US military’s role and influence on domestic intelligence.

The vast scale of this effort is reflected in a number of government social media surveillance patents granted this year, which relate to a spy program that the Trump administration outsourced to a private company last year. Experts interviewed by Motherboard say that the Pentagon’s new technology research may have played a role in amendments this April to the Joint Chiefs of Staff homeland defense doctrine, which widen the Pentagon’s role in providing intelligence for domestic “emergencies,” including an “insurrection.”

US ARMY TURNS TO THE HOMELAND

It’s no secret that the Pentagon has funded Big Data research into how social media surveillance can help predict large-scale population behaviours, specifically the outbreak of conflict, terrorism, and civil unrest.

Much of this research focuses on foreign theatres like the Middle East and North Africa — where the 2011 Arab Spring kicked off an arc of protest that swept across the region and toppled governments.

Since then, the Pentagon has spent millions of dollars finding patterns in posts across platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and beyond to enable the prediction of major events.

But the Pentagon isn’t just interested in anticipating surprises abroad. The research also appears to be intended for use in the US homeland.

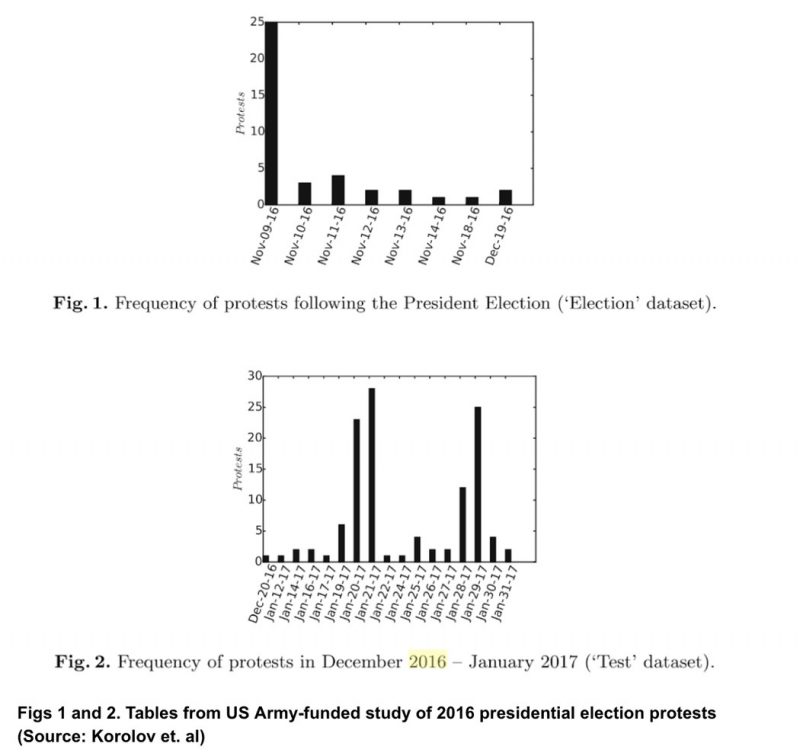

In August, a US Army-backed study on civil unrest within the US homeland was published in an obscure anthology of papers presented to a Big Data conference in Kiev, Ukraine, which took place in early June. The anthology was released as part of Springer-Nature’s Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing book series.

The paper in question is a study of the link between social media and anti-Trump protests after the 2016 presidential elections, titled “Social Network Structure as a Predictor of Social Behavior: The Case of Protest in the 2016 US Presidential Election.” The study was funded by the US Army Research Laboratory (ARL), which is part of the US Army’s Research Development and Engineering Command (RDECOM).

Written by researchers at America’s oldest technological university, the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in New York, the paper concludes that protests after the US elections could have been predicted by analysing the Twitter posts of millions of American citizens in the lead-up to the demonstrations.

After Trump’s election, there were immediate large-scale ‘Not Our President’ protests across the US in direct response to his victory, a few of which became violent. This has been followed by numerous other protests such as the Women’s March events in January, demonstrations against Trump’s travel ban, among others.

“Civil unrest is associated with information cascades or activity bursts in social media, and these phenomena may be used to predict protests, or at least peaks of protest activity,” the paper says. “Failure to predict an unexpected protest may result in injuries or damage.”

Authors Molly Renaud, Rostyslav Korolov, David Mendonca, and William Wallace of RPI’s Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering explain that their study tries to identify the “structural properties of social networks in order to predict protest occurrence,” by employing “keyword-defined Twitter datasets associated with the 2016 US Presidential Election”.

REAL-TIME SOCIAL MEDIA TRACKING OF US CITIZENS

Datasets for the research were collected using the Apollo Social Sensing Tool, a real-time event tracking software that collects and analyses millions of social media posts.

The tool was originally developed under the Obama administration back in 2011 by the US Army Research Laboratory and US Defense Threat Reduction Agency, in partnership with Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the University of Illinois, IBM, and Caterva (a social marketing company that in 2013 was folded into a subsidiary of giant US government IT contractor, CSC). Past papers associated with the project show that the tool has been largely tested in foreign theatres like Haiti, Egypt, and Syria.

But the use of the Apollo tool to focus on protests in the US homeland has occurred under the Trump administration. The ‘election’ dataset compiled using Apollo for the 2018 US Army-funded study is comprised of 2.5 million tweets sent between October 26, 2016, and December 20, 2016, using the words “Trump”, “Clinton,” and “election.”

Tweets were geolocated to focus on “locations where protests occurred following the election” based on user profiles. Locations were then triangulated against protest data from “online news outlets across the country.”

The millions of tweets were used to make sense of the “frequencies of the protests in 39 cities” using 18 different ways of measuring the “size, structure and geography” of a network, along with two ways of measuring how that network leads a social group to become “mobilized,” or take action.

The paper concludes that by “examining the structure of social networks as related in tweets related to the 2016 US Presidential Election, a relationship is identified between network structure and protest occurrence.” The model demonstrates that social media plays a catalyzing role in the mobilization of social groups before a protest, in a way “which is observable in advance of protest occurrences. This may be of use in preparing for such an event, and help minimize injuries and property damage.”

In short, this means that “the social network can be a predictor of mobilization, which in turn is a predictor of the protest.” This pivotal finding means that extensive real-time monitoring of American citizens’ social media activity can be used to predict future protests.

More work is needed to beef up the accuracy of the model, though. This model is still only 44 percent accurate five days before the protest, with accuracy increasing up to 82 percent closer to the incident.

“If you look at the long term trajectory of Pentagon, and intelligence agency desires for this sort of profiling and surveillance, these social media monitoring projects fits a deep pattern of institutional surveillance desires”

Acknowledgements at the end of the paper confirm that the “research is sponsored by the Army Research Laboratory.” The paper includes the caveat that the research does not necessarily represent the US government’s “official policies.” And of course, the US military funds a vast amount of research pursued independently, much of which does not necessarily go anywhere.

On the other hand, the paper also adds that, “the US Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes,” and according to the ARL itself, the Laboratory “applies the extensive research and analysis tools developed in its direct mission program to support ongoing development and acquisition programs” across the US Army and industry partners: “ARL has consistently provided the enabling technologies in many of the Army’s most important weapons systems.”

Whatever the case, the US military funding remains a clear indication of US government interest.

The Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute is part of the ARL Network Science Collaborative Technology Alliance (NS CTA), a consortium of three industrial research labs and 14 universities which receives multi-million dollar support from the US Army Research Laboratory.

The last round of multi-million dollar five-year funding was received by Rensselaer in 2015. Research priorities are closely and continuously developed within the CTA through collaboration between university scientists, industry and the US military.

A lead author of the paper, Rostyslav Korolov—identified as the point of contact about the research—is a PhD candidate at RPI focusing on “prediction of human behavior based on social media communications” under the ARL Alliance, and liaised closely with the US military while working on the anti-Trump protest study.

“While working on this project I’ve spent two months on an internship at the US Army Research Laboratory and a year as a visiting scholar at the Network Science Center, United States Military Academy, West Point,” his RPI bio explains.

Motherboard attempted to reach the authors of the paper through multiple requests, but did not receive any response to questions about the study and the reason for its focus on protests at home.

However, Tom Moyer, a spokesman for the ARL provided us the following statement: “The Army Research Laboratory, through its collaborative alliances, cooperative agreements and other instruments, funds scientific exploration across a large spectrum to broaden the scientific knowledge base that could lead to a more capable Army.

That is not to say that the laboratory, or the US Army, agrees with every conclusion drawn from principal investigators who are trying to answer difficult research questions. Our collaborators often go deep into areas of research that are sometimes high risk, but often result in the transfer of knowledge that increases scientific understanding.”

Moyer explained that the US Army selected this particular research project under a broader program theme titled, “Social/cognitive-theory-guided knowledge networks enrichment, predictive and prescriptive analysis.” The program’s goals, he said, include developing “mathematical understanding of strength and mobility of self-forming networks.”

Asked what the ARL hoped to achieve by funding this research, Moyer told me that “the researcher’s expertise in disaster research via computational science led to ARL’s funding decision. Fundamental research into complex networks, including social networks, is extremely valuable and could provide insight into the prediction and evolution of major events. This insight can aid nations for planning and undertaking relief response to natural and manmade disasters.”

David Price, a professor of sociology and anthropology at St. Martin’s University told me “the Pentagon throws a lot of money at a lot of projects, many of them downright silly.”

“But if you look at the long term trajectory of Pentagon, and intelligence agency desires for this sort of profiling and surveillance, these social media monitoring projects fits a deep pattern of institutional surveillance desires,” he added.

Price is the world’s leading expert on the relationships between US anthropologists, social scientists, and US military intelligence agencies, the author of the book Weaponizing Anthropology: Social Science in Service of the National Security State, and has served on several American Anthropological Associations commissions and task forces dealing with the ethical issues of engaging with the US intelligence community. He describes the latest research as “really an extension of the once frightening, now mundane expression of a national panopticon expressed by the Total Information Awareness program when first conceived in 2002, and quickly withdrawn.”

Total Information Awareness was a major Bush administration initiative aimed at monitoring the entire American population through electronic surveillance. Though defunded in 2003 after extensive media criticism, its core architecture was adopted by the National Security Agency (NSA) where it is now “quietly thriving” according to the New York Times.

SOCIAL MEDIA SNOOPING: AN AMERICAN TRADITION

The Trump election study is just the latest in a spate of research pursued by US government-funded scientists to predict civil unrest through social media surveillance.

Much of that research has been funded by the US government’s spy research organisation, IARPA—the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency—for a longtime project known as Embers that examined trends in foreign theatres. But even this research appears to have potential domestic applications.

Established in April 2012, the project (which stands for Early Model Based Event Recognition using Surrogates) generated seven-day advanced forecasts based on “open-source indicators”—social media, satellite imagery, and more than 200,000 blogs that are publicly available. An average of 80 to 90 percent of its forecasts were accurate, according to studies related to the program.

Teams made up mainly from three external industry partners, HRL Laboratories, Raytheon BBM Technologies, and Virginia Tech, were involved in developing the technologies behind Embers, which was funded by a $22 million contract by IARPA.

Like many other similar projects sponsored by IARPA, Embers was funded through the US government’s Interior Business Center (previously known as the National Business Center) according to documents and publications related to the program.

The IBC is the business management and IT service provider for the US Department of the Interior as well as other domestically-focused federal agencies, including the Department of Homeland Security—indicating that IARPA-funded technologies can easily be transitioned for homeland applications.

The current uses of the technology are not public knowledge and no longer under the reach of any form of public accountability. But the entity that is still running the technology is a major US government contractor.

In 2017, IARPA announced that Embers had been moved into the commercial arm of Virginia Tech through its Applied Research Corporation (VTARC.) The move would now enable a range of US-based organizations to “purchase the system’s daily forecasts for a particular set of countries.”

IARPA spokesman Charles Carithers told me that Embers was now being offered as “a subscription service” to US clients.

There is no official information available about who Virginia Tech’s Applied Research Corporation works with in relation to the social media surveillance tools it developed through IARPA’s Embers program. But a job advert from early 2018 issued by the company for a research analyst specialising in “ISR”—intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance—mentions work “to support US government customers” (archived here):

“The ISR Research Analyst will perform thorough research and analyses on open source and customer-provided data to extract meaningful information in support of the customer’s mission goals. Primary responsibilities include collecting, processing, and analyzing technical data, searching and applying information from the primary scientific literature, developing clear visualizations of the data (graphs, tables, etc.), identifying emerging technologies, and composing clear and concise draft technical reports to support US government customers.”

The job description further stipulates the need for applicants to hold secret—and ideally Top Secret—security clearance.

In short, in 2017 the Trump administration moved IARPA’s Embers social media surveillance program into the private sector under VTARC. Yet one of VTARC’s customers using these surveillance tools is the Trump administration, and based on the job listing, it appears to deal with secret and top secret information.

The move by VTARC illustrates that even with the best of intentions, independent scientists receiving US government funding for such research have no control or oversight over the uses of their work. According to Price, the impact of the research could still be insidious even if the social scientists involved did not hold any conflicts of interest as such.

“This sort of military funded social science research tends to occur in an ideological echo chamber, where groupthink predominates and dissent or concerns about the applications of this work is missing,“ he told me. “Among the basic assumptions that social scientists outside this group would question are assumptions that civil unrest or protests are not core elements of democracy that need to be protected, [rather than] undermined by surveillance—and the oppression that follows such surveillance.”

VTARC did not respond to requests for details on who the corporation’s clients are for its social media surveillance tools originally developed under Embers.

EVADING ACCOUNTABILITY

The move to the private sector has helped circumvent prospects for public sector accountability, by keeping the most sensitive details of the program outside the scope of Freedom of Information Act requests.

Earlier this year, the ACLU filed several FOIA requests to a range of US government agencies over concerns that domestic social media surveillance had “spiked” under the Trump administration. In early September, the ACLUreleased documents showing that state and federal law enforcement agencies were collaborating to ramp up “Social Networking” surveillance of domestic activists over concerns about protests against the Keystone XL pipeline—the measures were justified as “anti-terrorism.”

Two weeks later, an image contained in a Massachusetts state police tweet accidentally revealed that a police computer monitor had bookmarked several Facebook groups for left-wing activist organizations with an anti-Trump slant.

While the ACLU has been able to confirm that under Trump, government departments like the Departments of Defense, Justice, and Homeland Security are accelerating domestic social media surveillance in relation to anticipated anti-Trump protest incidents, these FOIA requests have not revealed the technologies being deployed to do so.

“This kind of technology-enabled surveillance of social media will likely suppress dissent and lead to biased targeting of racial and religious minorities”

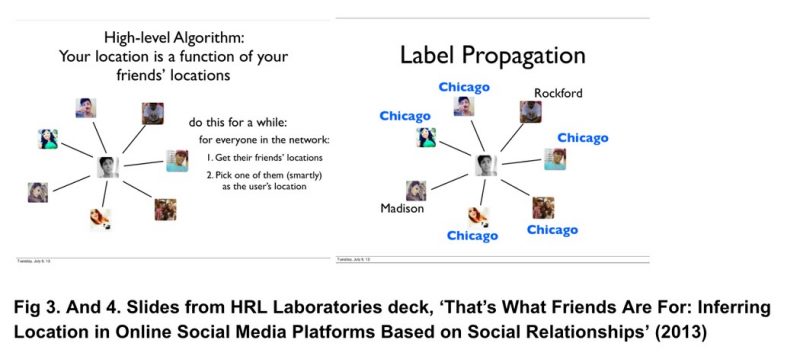

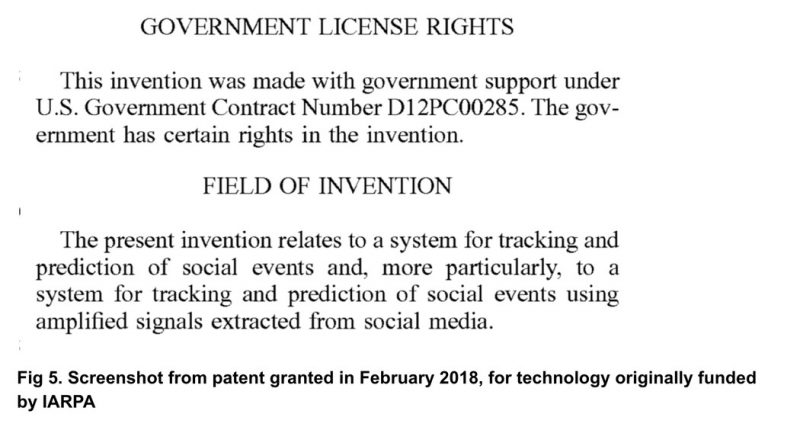

Though precise information on VTARC’s social media surveillance capabilities is unavailable, a sense of the capability can be gleaned from two related patent applications, originally filed around 2013 and 2014 by HRL Laboratories LLC, which were successfully granted in 2018.

HRL is jointly owned by General Motors and Boeing. The successful patents relate to a whole ecosystem of social media surveillance technologies, many of them still in application, developed over nearly a decade with funding from IARPA.

One patent is titled “Tracking and prediction of societal event trends using amplified signals extracted from social media,” filed in 2013 and granted in February 2018. The invention, says the patent, relates to “a system for tracking and prediction of social events using amplified signals extracted from social media.”

Another patent is titled “Inferring the location of users in online social media platforms using social network analysis,” filed in 2013 and partially granted in October 2017.

The body of scientific literature related to these patents, reviewed by Motherboard, demonstrates a sophisticated technology suite capable of locating the “home” position of users to within 10 kilometers for millions of Twitter accounts, and predicting thousands of incidents of civil unrest from micro-blogging streams on Tumblr.

A 2013 slide presentation prepared for HRL laboratories by patent inventor David A. Jurgens, although his research was based on Latin America, showcases examples of how the technology can locate people from within the United States.

Both patents, which refer to a massive body of previous IARPA-Department of Interior funded patents, make clear that they were created with support from the US government which retains “certain rights in the invention.”

The Pentagon’s upgraded homeland defense doctrine seems to be part of a wider effort by the Trump administration to prepare for domestic civil unrest in coming months and years.

Although these technologies were developed under the Obama administration, it appears their use is being accelerated by the Trump administration—and by moving the Embers program to which these technologies relate into the private sector, this acceleration is occurring in a way that sits beyond public scrutiny or accountability.

“This kind of technology-enabled surveillance of social media will likely suppress dissent and lead to biased targeting of racial and religious minorities,” Hugh Handeyside, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s National Security Project, told me. “We need to know much more about any proposed policies or programs and their effect on rights that the Constitution protects.”

MILITARIZING THE HOMELAND

The intensification of US social media surveillance coincides with the Trump administration’s augmentation this year of the Pentagon’s role in homeland security.

In April 2018, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff issued an updated doctrine on homeland defense. The new doctrine underscores the extent to which the Trump administration wants to consolidate homeland defense and security under the ultimate purview of the Pentagon.

The US military’s traditional function is to defend the US from foreign threats rather than interfere with domestic issues. After 9/11, homeland defense and security doctrines have been gradually pushed toward closer integration with the US military in a process first accelerated by the Bush administration.

As with previous versions of the doctrine, the document states that ‘Lead Federal Authority’ (LFA) for “homeland security” is the Department of Homeland Security, but simultaneously goes to pains to emphasize again and again how the Department of Defense (DOD) must be active at the epicentre of almost all homeland affairs.

This is achieved by interlinking homeland security indelibly with “homeland defense”—the latter defined as a US military function. The doctrine further institutionalizes the necessity of seamless Pentagon “support” for “homeland security“ operations on land and sea:

“DOD is a key part of the HS [homeland security] enterprise that protects the homeland through two distinct but interrelated missions, HD [homeland defense] and DSCA [defense support for civil authorities]. DOD is the federal agency with lead responsibility for HD, which may be executed by DOD alone… or include support from other USG departments and agencies…. While these missions are distinct, some department roles and responsibilities overlap and operations require extensive coordination between lead and supporting agencies. HD and DSCA operations may occur in parallel and require extensive integration and synchronization with HS operations.”

These stipulations are not entirely novel compared to previous iterations. Yet they are augmented by some subtle but unprecedented changes concerning the powers to respond to a domestic “insurrection” and the role of Pentagon intelligence in such a response.

“The whole concept of ‘homeland defense’ as a military function may come as a surprise to those who supposed that this is the purpose of the Department of Homeland Security,” Steven Aftergood, who directs the Federation of American Scientists’ Project on Government Secrecy, told me about the updated doctrine. “But in fact the Department of Defense does have a role not only in defense against foreign invasion but also in maintaining civil control. These roles are expanded and elaborated in the new Joint Publication.”

The intensifying militarization of the homeland is happening right now on the pretext of dealing with migrants. Defense Secretary James Mattis has not only supported DHS’s requests for the US military to accommodate two “temporary“ camps to detain migrants during the child separation crisis, but has also approved Trump’s request to dispatch 4,000 National Guard troops to secure the US-Mexico border.

US MILITARY TO SUPPORT DOMESTIC SURVEILLANCE

Crucially, Aftergood pointed out that some of the most notable changes in the doctrine concern ensuring that classification does not prevent homeland agencies from accessing Pentagon intelligence. The upgraded doctrine says that Pentagon resources can be mobilized for domestic surveillance or “information support” in the context of emergencies.

“Military information support forces and equipment may also be used to conduct civil authority information support activities during domestic emergencies within the boundaries of the US homeland,” it reads.

Accordingly, the doctrine calls for the Pentagon to engage in more proactive information sharing with civilian authorities at home, requiring a decreased reliance on classification. “DOD’s over-reliance on the classified information system for both classified and unclassified information is a frequent impediment,” the document says.

In simpler terms, the doctrine insists that classification should not impede the Pentagon from sharing intelligence with domestic agencies, especially in the context of “civil authority information support“ in homeland emergencies.

According to Price, this has ominous implications given that the NSA is a DOD agency. The import is that under the new doctrine, there are greater opportunities to connect domestic intelligence gathered by the NSA with the social media data of American citizens. “At least the data feeding these surveillance and predictive models comes from public social media data,“ Price told me.

“But given [Edward] Snowden’s revelations of CIA and NSA widespread surveillance, and the historical abuses of military and civilian intelligence agencies it is a reasonable assumption that these tools sorting and profiling public social media will be used to select groups of Americans, engaging in lawful acts of political dissent, who will have email, SMS, and voice communications monitored by military or civilian intelligence agencies.”

DOMESTIC INSURRECTION: A PENTAGON PROBLEM

The most pertinent section of the upgraded homeland defense doctrine for this story concerns the powers available to the President in the case of “insurrection,” a major rebellion which either state governors or the President himself deem to fundamentally threaten the rule of law.

Once again, though not a new addition to the doctrine, vaguer language is introduced including a stipulation that the authority for a US Army response to an “insurrection” will constitute a “HD [homeland defense]-related purpose.”

This is the first time that an “insurrection” has been described using the phrase “homeland defense,” implying that the response would come under Pentagon jurisdiction. Referring to the US Code’s delineation of insurrection powers (Title 10, USC, Sections 251–255), the doctrine affirms that:

“These statutory provisions allow the President, at the request of a state governor or legislature, or unilaterally in some circumstances, to employ the US Armed Forces to suppress insurrection against state authority, to enforce federal laws, or to suppress rebellion. When support is directed for such HD-related purposes in the US [emphasis added], the designated JFC [Joint Force Commander] should utilize this special application knowing the main purpose of such employment is to help restore law and order with minimal harm to the people and property and with due respect for all law-abiding citizens.”

This invocation of the Insurrection Act connects it directly with homeland defense powers under Pentagon command—a move which is in tension with the idea that DSCA, or “Defence Support to Civil Authorities,” should be led by the DHS, instead giving ultimate authority for such an operation to the DOD.

I asked Aftergood whether he thought this amendment should raise alarm bells. On the one hand, he remarked that the US military traditionally had little intrinsic interest in homeland operations. “I do think the changes in DOD doctrine are noteworthy. But it is also true that as a military organization, DOD is generally scrupulous about adhering to defined authority, including limitations to that authority,“ he said. “The Department of Homeland Security is in some respects less disciplined, and more prone to improvise in troublesome ways.”

How far that caution applies in the context of a DOD led by a Trump appointee is an open question. But Aftergood also described the amendments as a potential danger to American democracy: “The whole subject bears careful monitoring, since it potentially poses a challenge to civilian control of government and to the integrity of democratic institutions,” he said.

I also spoke to William C. Banks, distinguished professor and founding director of the Institute for National Security and Counterterrorism at Syracuse University’s College of Law, who largely agreed with Aftergood’s assessment. “There is cause for concern due to the ambiguities embedded in the law and the federal guidance supplied through civilian and military agencies on homeland defense,“ Banks warned. “It is not unusual for doctrines like this to be quietly updated and they do this almost every year. But these changes are always worth monitoring due to the risk to democracy.”

I asked Banks, co-author of Soldiers on the Homefront: The Domestic Role of the American Military, about the doctrine’s description of an “insurrection” as a “homeland defense“ issue.

“The US military role in the homeland is not new, but in this case there’s a tension between DSCA [Defense Support for Civil Authorities] and homeland defense, because in one setting civilians are in charge, and in another setting the military are in charge,” he said. “The changes to doctrine are not dramatic, but they could make it more likely, maybe inevitable, that those jurisdictional issues might come together or clash in some way.”

The outcome of such a clash could end up putting Trump’s Defense Secretary in charge of a response to a domestic emergency categorized by Trump as an “insurrection.“ Taken in tandem with the US military’s sudden interest in predicting anti-Trump protests after the 2016 elections, the Pentagon’s upgraded homeland defense doctrine seems to be part of a wider effort by the Trump administration to prepare for domestic civil unrest in coming months and years.

Indeed, according to Banks, the changes to the doctrine in April could well have occurred as an effort to adapt to the technological developments in social media surveillance under the Trump administration described earlier in this story.

“One reason that doctrines are updated is due to changes in technology—military intelligence capabilities will adapt to new technologies, the power of social media, new cybersecurity capabilities,” he said. “The more we learn about those, the more we can envisage new threats and new opportunities to address them. So this new research on social media surveillance is exactly the kind of thing that could prompt changes in doctrine. The Pentagon’s support for this kind of research is concerning and should be closely monitored.”

The Pentagon did not respond to Motherboard’s question about any possible connection between the upgraded homeland defense doctrine and the Pentagon’s new research on social media surveillance.

The problem is that however seemingly minor, “shifts in homeland defense doctrine increasingly create possibilities for military and civilian intelligence agencies to engage in political surveillance and harassment,” said Price. “With an unstable president who frequently is unable to differentiate between political and legal threats to him and threats to the nation, we must worry about what President Trump may consider an ‘insurrection’ worth of massive military surveillance.”

This article was originally published by “Motherboard“

The 21st Century