A rant by Mike Pompeo regarding what the U.S. should do with China led to a fruitful exchange between an old China, and an old Soviet hand

Quick. Somebody tell Mike Pompeo. The secretary of state is not supposed to play the role of court jester — the laughing stock to the world.

There was no sign that any of those listening to his “major China policy statement” last Thursday at the Nixon Library turned to their neighbor and said, “He’s kidding, right? Richard Nixon meant well but failed miserably to change China’s behavior? And now Pompeo is going to put them in their place?”

Yes, that was Pompeo’s message. The torch has now fallen to him and the free world. Here’s a sample of his rhetoric:

“Changing the behavior of the CCP [Chinese Communist Party] cannot be the mission of the Chinese people alone. Free nations have to work to defend freedom. …

“Beijing is more dependent on us than we are on them (sic). Look, I reject the notion … that CCP supremacy is the future … the free world is still winning. … It’s time for free nations to act … Every nation must protect its ideals from the tentacles of the Chinese Communist Party. … If we bend the knee now, our children’s children may be at the mercy of the Chinese Communist Party, whose actions are the primary challenge today in the free world. …

“We have the tools. I know we can do it. Now we need the will. To quote scripture, I ask is ‘our spirit willing but our flesh weak?’ … Securing our freedoms from the Chinese Communist Party is the mission of our time, and America is perfectly positioned to lead it because … our nation was founded on the premise that all human beings possess certain rights that are unalienable. And it’s our government’s job to secure those rights. It’s a simple and powerful truth. It’s made us a beacon of freedom for people all around the world, including people inside of China.

“Indeed, Richard Nixon was right when he wrote in 1967 that “the world cannot be safe until China changes.” Now it’s up to us to heed his words. … Today the free world must respond. …”

Trying to Make Sense of It

Over the weekend an informal colloquium-by-email took pace, spurred initially by an op-ed article by Richard Haass critiquing Pompeo’s speech. Haass has the dubious distinction of having been director of policy planning for the State Department from 2001 to 2003, during the lead-up to the attack on Iraq.

Four months after the invasion he became president of the Council on Foreign Relations, a position he still holds. Despite that pedigree, the points Haass makes in “What Mike Pompeo doesn’t understand about China, Richard Nixon and U.S. foreign policy” are, for the most part, well taken.

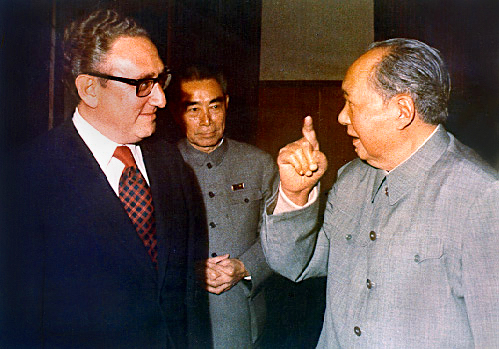

Haass’s views served as a springboard over the weekend to an unusual discussion of Sino-Soviet and Sino-Russian relations I had with Ambassador Chas Freeman, the main interpreter for Nixon during his 1972 visit to China and who then served as U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia from 1989 to 1992.

As a first-hand witness to much of this history, Freeman provided highly interesting and not so well-known detail mostly from the Chinese side. I chipped in with observations from my experience as CIA’s principal analyst for Sino-Soviet and broader Soviet foreign policy issues during the 1960s and early 1970s.

Ambassador Freeman:

As a participant in that venture: Nixon responded to an apparently serious threat to China by the USSR that followed the Sino-Soviet split. He recognized the damage a Soviet attack or humiliation of China would do to the geopolitical balance and determined to prevent the instability this would produce.

He offered China the status of (what I call) a “protected state” — a country whose independent existence is so important strategically that it is something we would risk war over.

Mao was sufficiently concerned about the prospect of a Soviet attack that he held his nose and welcomed this change in Sino-American relations, thereby accepting this American abandonment of the sort of hostility we are again establishing as outlined in Pompeo’s psychotic rant of last Thursday.

Nixon had absolutely zero interest in changing anything but China’s external orientation and consolidating its opposition to the USSR in return for the U.S. propping it up. He also wanted to get out of Vietnam, which he inherited from LBJ, in a way that was minimally destabilizing and thought a relationship with China might help accomplish that. It didn’t.

Overall, the maneuver was brilliant. It bolstered the global balance and helped keep the peace. Seven years later, when the Soviets invaded and occupied Afghanistan, the Sino-American relationship immediately became an entente — a limited partnership for limited purposes.

In addition to its own assistance to the mujahideen, China supplied the United States with the weapons we transferred to anti-Soviet forces ($630 million worth in 1987), supplied us with hundreds or millions of dollars worth of made-to-order Chinese-produced Soviet-designed equipment (e.g. MiG21s) and training on how to use this equipment so that we could learn how best to defeat it, and established joint listening posts on its soil to more than replace the intelligence on Soviet military R&D and deployments that we had just lost to the Islamic revolution in Iran.

Sino-American cooperation played a major role in bringing the Soviet Union down.

Apparently, Americans who don’t see this are so nostalgic for the Cold War that they want to replicate it, this time with China, a very much more formidable adversary than the USSR ever was.

Those who don’t understand what that engagement achieved argue that it failed to change the Chinese political system, something it was never intended to do. They insist that we would be better off returning to 1950s-style enmity with China. Engagement was also not intended to change China’s economic system either but it did.

China is now an integral and irreplaceable part of global capitalism. We apparently find this so unsatisfactory that, rather than addressing our own competitive weaknesses, we are attempting to knock China back into government-managed trade and underdevelopment, imagining that “decoupling” will somehow restore the economic strengths our own ill-conceived policies have enfeebled.

A final note. Nixon finessed the unfinished Chinese civil war, taking advantage of Beijing’s inability to overwhelm Taipei militarily. Now that Beijing can do that, we are unaccountably un-finessing the Taiwan issue and risking war with China — a nuclear power — over what remains a struggle among Chinese — some delightfully democratic and most not. Go figure.

Ray McGovern:

This seems a useful discussion — perhaps especially for folks with decades-less experience in the day-to-day rough and tumble of Sino-Soviet relations.

During the 1960s, I was CIA’s principal Soviet analyst on Sino-Soviet relations and in the early 1970s, as chief of the Soviet Foreign Policy Branch and Presidential Daily Brief writer for Nixon, I had a catbird seat watching the constant buildup of hostility between Russia and China, and how, eventually, Nixon and Henry Kissinger saw it clearly and were able to exploit it to Washington’s advantage.

I am what we used to be called an “old Russian hand” (like over 50 years worth if you include academe). So, my not being an “old China hand” except for the important Sino-Soviet issue, it should come as no surprise that my vantage point will color my views — especially given my responsibilities for intelligence support for the SALT delegation and ultimately Kissinger and Nixon — during the early 1970s.

I had been searching for a word to apply to Pompeo’s speech on China. Preposterous came to mind, assuming it still means “contrary to reason or common sense; utterly absurd or ridiculous.” Chas’s “psychotic rant” may be a better way to describe it. And it is particularly good that Chas includes several not widely known facts about the very real benefits that accrued to the U.S. in the late 70’s and 80’s from the Sino-U.S. limited partnership.

Having closely watched the Sino-Soviet hostility rise to the point where, in 1969, the two started fighting along the border on the Ussuri River, we were able to convince top policy makers that this struggle was very real — and, by implication, exploitable.

Moscow’s unenthusiastic behavior on the Vietnam War showed that, while it felt obliged to give rhetorical support, and an occasional surface-to-air missile battery, to a fraternal communist country under attack, it had decided to give highest priority to not letting Moscow’s involvement put relations with the U.S. into a state of complete disrepair. And, specifically, not letting China, or North Vietnam, mousetrap or goad the Soviets into doing lasting harm to the relationship with the U.S.

At the same time, the bizarre notion prevailing in Averell Harriman’s mind at the time as head of the U.S. delegation to the Paris peace talks, was that the Soviets could be persuaded to “use their influence in Hanoi” to pull U.S. chestnuts out of the fire. It was not only risible but also mischievous.

Believe it or not, that notion prevailed among the very smart people in the Office of National Estimates as well as other players downtown. Frustrated, I went public, publishing an article, “Moscow and Hanoi,” in Problems of Communism in May 1967.

After Kissinger went to Beijing (July 1971) — followed in February 1972 by Nixon — we Soviet analysts began to see very tangible signs that Moscow’s priority was to prevent the Chinese from creating a closer relationship with Washington than the Soviets could achieve.

In short, we saw new Soviet flexibility in the SALT negotiations (and, in the end, I was privileged to be there in Moscow in May 1972 for the signing of the Antiballistic Missile Treaty and the Interim Agreement on Offensive Arms). Even earlier, we saw some new flexibility in Moscow’s position on Berlin.

To some of us who had almost given up that a Quadripartite Agreement could ever be reached, well, we saw it happen in September 1971. I believe the opening to China was a factor.

So, in sum, in my experience, Chas is quite right in saying, “Overall, the maneuver was brilliant.” Again, the Soviets were not about to let the Chinese steal a march in developing better ties with the U.S. And I was able to watch Soviet behavior very closely in the immediate aftermath of the U.S. opening to China.

As for the future of Sino-Soviet relations, we were pretty much convinced that, to paraphrase that “great” student of Russian history, James Clapper, the Russians and Chinese were “almost genetically driven” to hate each other forever. In the 1980s, though, we detected signs of a thaw in ties between Moscow and Beijing.

To his credit, Secretary of State George Shultz was very interested in being kept up to date on this, which I was able to do, even after my tour briefing him on the PDB ran out in 1985. (I was acting chief of the Analysis Group at the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) for two years … (an outstanding outfit later banned by Robert Gates.)

Some Observations

1 — Unless Pompeo had someone else take the exams for him at West Point, he has to be a pretty smart fellow. In other words, I don’t think he can claim “Invincible ignorance”, (a frame of mind that can let us Catholics off the hook for serious transgressions or ineptitude). The only thing that makes sense to me is that he is a MICIMATTer. MICIMATT for the Military-Industrial-Congressional-Intelligence-MEDIA-Academia-Think-Tank complex (MEDIA is all caps because it is the sine quo non, the linchpin) For example: Item: “Officials cite ‘keeping up with China’ as they award a $22.2 billion contract to General Dynamics to build Virginia-class submarines.” December 4, 2019

2 — I sometimes wonder what China, or Russia, or anyone thinks of a would-be statesman with the puerile attitude of a U.S. secretary of state who brags: “I was the CIA director. We lied, we cheated, we stole. We had entire training courses. It reminds you of the glory of the American experiment.”

3 — If memory serves, annual bilateral trade between China and Russia was between $200 and 400 MILLION during the 1960’s. It was $107 BILLION in 2018.

4 — The Chinese no longer wear Mao suits; and they no longer issue 178 “SERIOUS WARNINGS” a year. I can visualize, though, just one authentically serious warning about U.S. naval operations in the South China Sea or the Taiwan Strait. Despite the fact that there is no formal military alliance with Russia, I suspect the Russians might decide to do something troublesome — perhaps even provocative — in Syria, in Ukraine, or even in some faraway place like the Caribbean — if only to show a modicum of solidarity with their Chinese friends who at that point would be in direct confrontation with U.S. ships far from home. That, I think, is how far we have come in Pompeo’s benighted attempt to throw his weight around at both countries.

Three years ago, I published here an article titled “Russia-China Tandem Shifts Global Power.” Here are some excerpts:

“Gone are the days when Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger skillfully took advantage of the Sino-Soviet rivalry and played the two countries off against each other, extracting concessions from each. Slowly but surely, the strategic equation has markedly changed – and the Sino-Russian rapprochement signals a tectonic shift to Washington’s distinct detriment, a change largely due to U.S. actions that have pushed the two countries closer together.

But there is little sign that today’s U.S. policymakers have enough experience and intelligence to recognize this new reality and understand the important implications for U.S. freedom of action. Still less are they likely to appreciate how this new nexus may play out on the ground, on the sea or in the air.

Instead, the Trump administration – following along the same lines as the Bush-43 and Obama administrations – is behaving with arrogance and a sense of entitlement, firing missiles into Syria and shooting down Syrian planes, blustering over Ukraine, and dispatching naval forces to the waters near China.

But consider this: it may soon be possible to foresee a Chinese challenge to “U.S. interests” in the South China Sea or even the Taiwan Strait in tandem with a U.S.-Russian clash in the skies over Syria or a showdown in Ukraine.

A lack of experience or intelligence, though, may be too generous an interpretation. More likely, Washington’s behavior stems from a mix of the customary, naïve exceptionalism and the enduring power of the U.S. arms lobby, the Pentagon, and the other deep-state actors – all determined to thwart any lessening of tensions with either Russia or China.

After all, stirring up fear of Russia and China is a tried-and-true method for ensuring that the next aircraft carrier or other pricey weapons system gets built.

.@SecPompeo: The old paradigm of blind engagement with China has failed. We must not continue it. We must not return to it. We need a strategy that protects the American economy and our way of life. The free world must triumph over this new tyranny. pic.twitter.com/6F5O50qlYf

— Department of State (@StateDept) July 27, 2020

Like subterranean geological plates shifting slowly below the surface, changes with immense political repercussions can occur so gradually as to be imperceptible until the earthquake.

As CIA’s principal Soviet analyst on Sino-Soviet relations in the 1960s and early 1970s, I had a catbird seat watching sign after sign of intense hostility between Russia and China, and how, eventually, Nixon and Kissinger were able to exploit it to Washington’s advantage.

The grievances between the two Asian neighbors included irredentism: China claimed 1.5 million square kilometers of Siberia taken from China under what it called “unequal treaties” [they were unequal] dating back to 1689.

This had led to armed clashes during the 1960s and 1970s along the long riverine border where islands were claimed by both sides.

In the late 1960s, Russia reinforced its ground forces near China from 13 to 21 divisions. By 1971, the number had grown to 44 divisions, and Chinese leaders began to see Russia as a more immediate threat to them than the U.S. …

Enter Henry Kissinger, who visited Beijing in July 1971 to arrange the precedent-breaking visit by President Richard Nixon the following February.

What followed was some highly imaginative diplomacy orchestrated by Kissinger and Nixon to exploit the mutual fear China and the USSR held for each other and the imperative each saw to compete for improved ties with Washington.

Triangular Diplomacy

Washington’s adroit exploitation of its relatively strong position in the triangular relationship helped facilitate major, verifiable arms control agreements between the U.S. and USSR and the Four Power Agreement on Berlin. The USSR even went so far as to blame China for impeding a peaceful solution in Vietnam.

It was one of those felicitous junctures at which CIA analysts could jettison the skunk-at-the-picnic attitude we were often forced to adopt. Rather, we could in good conscience chronicle the effects of the U.S. approach and conclude that it was having the desired effect. Because it was.

Hostility between Beijing and Moscow was abundantly clear. In early 1972, between President Nixon’s first summits in Beijing and Moscow, our analytic reports underscored the reality that Sino-Soviet rivalry was, to both sides, a highly debilitating phenomenon.

Not only had the two countries forfeited the benefits of cooperation, but each felt compelled to devote huge effort to negate the policies of the other. A significant dimension had been added to this rivalry as the U.S. moved to cultivate better relations simultaneously with both. The two saw themselves in a crucial race to cultivate good relations with the U.S.

The Soviet and Chinese leaders could not fail to notice how all this had increased the U.S. bargaining position. But we CIA analysts saw them as cemented into an intractable adversarial relationship by a deeply felt set of emotional beliefs, in which national, ideological, and racial factors reinforced one another.

Although the two countries recognized the price they were paying, neither seemed able to see a way out. The only prospect for improvement, we suggested, was the hope that more sensible leaders would emerge in each country. But this seemed an illusory expectation at the time.

We were wrong about that. Mao Zedong’s and Nikita Khrushchev’s successors proved to have cooler heads.

The U.S., under President Jimmy Carter, finally recognized the communist government of China in 1979 and the dynamics of the triangular relationships among the U.S., China and the Soviet Union gradually shifted with tensions between Beijing and Moscow lessening.

Yes, it took years to chip away at the heavily encrusted mistrust between the two countries, but by the mid-1980s, we analysts were warning policymakers that “normalization” of relations between Moscow and Beijing had already occurred slowly but surely, despite continued Chinese protestations that such would be impossible unless the Russians capitulated to all China’s conditions.

For their part, the Soviet leaders had become more comfortable operating in the triangular environment and were no longer suffering the debilitating effects of a headlong race with China to develop better relations with Washington.

A New Reality

Still, little did we dream back then that as early as October 2004 Russian President Putin would visit Beijing to finalize an agreement on border issues and brag that relations had reached “unparalleled heights.” He also signed an agreement to jointly develop Russian energy reserves.

A revitalized Russia and a modernizing China began to represent a potential counterweight to U.S. hegemony as the world’s unilateral superpower, a reaction that Washington accelerated with its strategic maneuvers to surround both Russia and China with military bases and adversarial alliances by pressing NATO up to Russia’s borders and President Obama’s “pivot to Asia.”

The U.S.-backed coup in Ukraine on Feb. 22, 2014, marked a historical breaking point as Russia finally pushed back by approving Crimea’s request for reunification and by giving assistance to ethnic Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine who resisted the coup regime in Kiev. [Surprisingly, China decided not to criticize the annexation of Crimea.]

On the global stage, Putin fleshed out the earlier energy deal with China, including a massive 30-year natural gas contract valued at $400 billion. The move helped Putin demonstrate that the West’s post-Ukraine economic sanctions posed little threat to Russia’s financial survival.

As the Russia-China relationship grew closer, the two countries also adopted remarkably congruent positions on international hot spots, including Ukraine and Syria. Military cooperation also increased steadily.

Yet, a hubris-tinged consensus in the U.S. government and academe continues to hold that, despite the marked improvement in ties between China and Russia, each retains greater interest in developing good relations with the U.S. than with each other. …”

Good luck with that Secretary Pompeo.

Ray McGovern works with Tell the Word, a publishing arm of the ecumenical Church of the Saviour in inner-city Washington. Ray was a CIA analyst for 27 years, during which he led the Soviet Foreign Policy Branch and prepared “The President’s Daily Brief” for Nixon, Ford, and Reagan and conducted the early-morning briefings from 1981 to 1985. He is co-founder of Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity (VIPS).

Originally published by Consortium News

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.