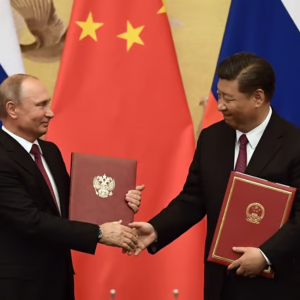

Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping added another to their count of 40–odd summit meetings when the Russian and Chinese presidents convened in Beijing, later proceeding to Harbin in Northeast China, for two days of talks that ended Friday. At 9:55 Thursday evening Beijing time, a day’s work done, the two sat behind a long table draped in green to address “members of the media,” as Xi put it.

Western officials and the media that clerk for them have done their best, per usual, to dismiss this latest encounter of the Russian and Chinese leaders as of no account, just two authoritarians bound together by nothing more than their shared enmity toward the West. Pay no attention. We ought not miss the significance of what Putin and Xi had to say this week to one another and to the rest of humanity. The world just turned once again.

The Kremlin was first to publish a transcript of their “Media Statement Following Russia–China Talks.” The two presidents spoke in turn—Xi, the host, going first and Putin to follow. Here is a snippet drawn from Xi’s remarks:

We signed joint statements on enhancing the comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation for a new era…. China and Russia have served as a role model by showing others ways of building state-to-state ties of a new kind and working together as two major neighboring powers … based on the principles of respect and equality.

Xi spoke in this vein for several minutes. Here is a little of what Putin then contributed:

Our talks have reaffirmed that Russia and China have similar or identical views on many international and regional issues.

Both countries have an independent and sovereign foreign policy. We are working together to create a fairer and more democratic multipolar world order based on the central role of the U.N. and its Security Council, international law, cultural and civilizational diversity, as well as a calibrated balance of interests of all members of the international community.

There are two things to note about these remarks straight off the top.

One, Western media have reported for months that there is a rift between Beijing and Moscow just below the surface. The Chinese do not approve of Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine, we have read. The bilateral relationship is radically unbalanced in Russia’s favor and of little use to China. Etc. This is nonsense, we can now see. In their brief presentation to the media and in other statements since, Xi and Putin have made it plain that there is virtually no air between the non–West’s two leading powers. As to the Ukraine question, to be noted right away, China has been studiously neutral while cognisant of the West’s provocations. Russia has never asked for more than this.

If Xi and Putin have made it a point to display their two nations’ closeness over the years—and their own as friends as well as statesmen, indeed—the two days they spent together this week mark an important public reaffirmation of their shared commitment to that “fairer and more democratic multipolar world” Putin mentioned Thursday. We have told you we have begun to build a new world order, they may as well have said. We’re on for this project. Together with others we will get this done.

Two, and related to the above, consider the May 16 joint statement from a few steps back. Apart from what is in it, what is conspicuously absent? There is no mention of the West, is there? The tone is strikingly self-confident and entirely self-referential. In my read, the two leaders could not have more clearly if subtly demonstrated that the new world order of which they speak is to be an initiative the non–West will advance whether or not the Atlantic world approves or wishes to participate in its construction.

In the first few weeks of this year, Sergei Lavrov gave a press conference that, although we could not know this at the time, previewed the just-concluded Sino–Russian summit and its larger significance. As the Russian foreign minister reviewed Russia’s foreign relations at the start of 2024, and listed the members of Moscow’s “close circle”—all non–Western nations, some of which are traditionally aligned with the U.S.—Lavrov announced Moscow’s intent “to remove any dependence on the West.” That is TASS, the Russian news agency, not me, although I commented on Lavrov’s remarks in this space at the time.

I also quoted a scholar of Russia and Eurasia named Gordon Hahn, who read the Lavrov press conference more acutely than anyone I know. Hahn’s remarks, during a segment of The Duran, the webcast produced daily in London, are worth requoting for their insight into what just happened when Putin and Xi met for their latest summit:

“For Russia, it looks now, the West is no longer its ‘Other.’… Russia has always identified itself, motivated itself, driven itself in relation to Europe. Now Putin is turning away from that. He said that we are no longer to define ourselves, look at ourselves, through the European prism. For now, we will put all our eggs in one basket, and that is Eurasia…. This close bilateral relationship, of Europe as Russia’s Other, is ending…

The joint statements Xi mentioned—Reuters reported Thursday that the two leaders signed one that runs to 7,000 words—are yet to be available at “Kremlin.ru” and “fmprc.org,” where documents of this kind are customarily made public. But as ScheerPost awaits these, it is already evident that Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin are intent on continuing to pry open the 21st century in the service of the new world order both describe as their overarching objective.

The timing of this summit is significant. It marks the 75th anniversary of Sino–Russian diplomatic relations. Moscow was the first nation to open formal ties with China after Mao declared the People’s Republic. Mao took Beijing October 1, 1949. The Soviet Union recognized on October 2. In referencing this occasion, Xi and Putin clearly intend to give relations as they are the ballast of history. This is not a passing partnership of convenience, they mean to say.

More immediately to the point, the Biden regime has dispatched a procession of officials to China in recent months, all to cajole China to bend to a lengthening list of sanctions, export controls, and tariffs intended to slow or subvert its economic development. Most recently, Secretary of State Blinken, during a three-day visit late last month, threatened Beijing with “consequences”—how they love to strike the ominous pose in Washington—if it did not stop supplying Russia with “dual use” products—semiconductors, industrial components and the like that the U.S. asserts may have military applications.

The extremely warm welcome Xi just extended to Putin is nothing if not a piquant reply to these threats and attempted coercions. Was it a pointed snub, a poke in the eye? It may look like one, but it would be a mistake to read it this way. In hosting the Russian leader, the greatest bête noire the U.S. has confected the whole of the postwar era, Xi gave us a display only of China’s indifference toward the policy hawks in Washington and among its trans–Atlantic satellites.

If Putin is intent on breaking Russia’s dependence on the West, as TASS well put it at the start of the year, Xi appears committed to a variant of the same position. China’s relations with the West are denser and more complex of course, because America and the Europeans are far more dependent on China’s economic production and investments. But Xi and Putin share a grasp of history’s movement that is far beyond Blinken and the rest of the Biden regime. Both leaders signaled this week they are confident that the dynamism that will define our new era—economic, diplomatic, even philosophic—no longer lies in the Atlantic world.

And so they got on with it this week.

■

It is two years and a few months since, on the eve of the Winter Olympics in Beijing, Putin and Xi made dramatically public their “Joint Statement on International Relations Entering a New Era and Global Sustainable Development.” This was a kind of declaration of intent in 5,500 words. In it the two leaders offered an analysis of global geopolitics and of the disorder that, then as now, threatened to overtake the world. Facing forward, they declared “a new world order”—this made the phrase official—as the planet’s most pressing imperative. I continue to view the “Joint Statement,” as I did at the time, as the most important political document advanced so far in the 21st century.

The latest Putin–Xi summit marks a significant recommitment to the principles set out in the statement of Feb. 4, 2022. The two again cite their dedication to rebuilding “a U.N.–centered system of international relations and an international order based on international law,” as Xi put it. He elaborated:

We have been coordinating our positions within multilateral platforms such as the United Nations, APEC [the Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation forum] and the G20 [the Group of 20 advanced and middle-income nations] to promote the emergence of a multipolar world and economic globalization based on genuine multilateralism.

That is the fourth of five principles Xi listed in his remarks to media. Here he is noting the last:

The fifth principle deals with promoting a political settlement for hotspots in the interest of truth and justice. Today’s world is still plagued by [a] Cold War mentality. Aspirations to securing a unilateral hegemony, bloc-based confrontation, and power politics pose a direct threat to peace and security for all countries around the world.

Unilateral hegemony, bloc-based confrontation: This sort of language will be familiar to those who have followed the public statements of senior Chinese officials, notably Xi and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, over the past several years. And I was pleased to note that a piece published May 16 by the PRC’s State Council cited the Five Principles Zhou Enlai famously formulated in the mid–1950s to define Chinese foreign policy. Xi’s five, in my read, are a modernized version of Zhou’s.

Zhou’s Principles, which were adopted by the Non–Aligned Movement at the famous conference Sukarno hosted at Bandung in 1955, are simply stated: respect for the sovereignty of others, respect for territorial integrity, noninterference in the internal affairs of others, a commitment to acting for mutual benefit, and a commitment to peaceful coexistence. I have detected these as subtext in Sino–Russian communiqués since the two sides issued the “Joint Statement” two years ago. Now they are restated publicly. It will be no bad thing if those coalescing around a new world order adopt them as the NAM did 70 years ago next year.

Something important must be said in this connection: Neither Xi nor Putin is “aligned” against the U.S. or its trans–Atlantic allies. Neither stands against cooperation with the U.S. or the rest of the West as they join others to build a new order. That is the concoction of U.S. officials and those who report upon them and is intended merely to confirm that China and Russia must always be understood to act as dangerous enemies of the U.S. in particular.

“China–Russia axis heralds an ominous future,” was the headline atop a piece the Center for European Policy Analysis published on the eve of the Putin–Xi summit. CEPA is, admittedly, one of those Washington civil-society groups, neoliberal to the core, that does not say who funds it while standing entirely in favor of “bloc confrontations.” But its take on Sino–Russian relations was typical of what we read in supposedly more serious mainstream media this week.

“Putin and Xi pledged a new era and condemned the United States,” Reuters reported May 15. The New York Times reported the same day, “Mr. Xi considers Russia an important counterweight in China’s rivalry with the United States.” It went on to explain, “The two leaders are expected to present a united front. But they have different agendas.”

Where do they get this pitiful stuff? Nobody condemned the U.S. in Beijing this week. Is there some question of Sino–Russian unity at this point? Can you find “competing agendas” in anything that has come out of the summit to date? I cannot. These are Western-centric fabrications intended to sustain the broadly held impression that Russia and China are malign adversaries, while obscuring the very salient fact that the only thing China and Russia oppose when they look Westward is hegemonic power.

■

The summits Putin and Xi are evidently fond of tend to be high-concept, as they say in Hollywood. This is as it should be, in my view. Ours is a moment of historical magnitude. We witness an immense shift in global power—at least to the extent those purporting to lead the West and their clerks in media fail to obscure this reality from us. But as China and Russia deepen and broaden their ties—“strategic cooperation,” a phrase used repeatedly this week, is new in the bilateral lexicon—the substantive density of the relationship is impossible to miss.

As both sides enthusiastically noted this week, bilateral trade came to $240 billion last year—$40 billion above the announced target. In the first two months of this year, two-way trade came to $37 billion, according to a Business Insider report published in March, suggesting a 2024 total of $222 billion, a touch below this year’s figure. But trade statistics tend to bounce around, one month to the next. Chinese customs reported trade of $76 billion in the first four months of this year, in line with a 2025 forecast of $300 billion—a 25 percent increase over two years.

As important as the volume and value is the currency in which trade is settled. China has been eager to internationalize the yuan for years, and Russia’s war in Ukraine has proven a big boost. Nearly a quarter of Russia’s imports are now settled in yuan, up from 4 percent a couple of years ago. No, we are not surprised to learn that the yuan surpassed the dollar last year as the most traded currency in the Moscow foreign-exchange market.

It is oil, gas, minerals and other resources eastward from Russia to China and manufactured goods and technology westward from China to Russia. So it is pipelines and tankers in one direction, by and large, and rail freight in the other. Bloomberg reported in March that Russia is spending heavily on improvements to its rail links to and from Chinese industrial centers, and once again there is no surprise here. This shows how the economic relationship is densifying as we speak.

Collaboration on nuclear power research, defense-related research, high-technology research: There appear to be few economic sectors Beijing and Moscow are leaving out. But what interests me most are advances in little corners of the Chinese economy, small business enterprises right down to Chinese medicine makers who want to see what’s what in the Russian market. This is people-to-people stuff, and so far as I can make out the Russians and Chinese leaderships count it important in the long-term, enduring densification of the relationship.

This is why, or one reason, Xi invited Putin to Harbin for the second day of their summit. Harbin is among China’s most interesting cities. Russians built the modern city after they completed a rail line in Northeast China in the first years of the last century. Its architecture remains a cosmopolitan mix of Russian, European and Chinese influences. If Xi and Putin wanted to display the depth and intimacy of Sino–Russian relations—altogether their organic nature—they could not have done better than to stroll around Harbin like a couple of companionable, pose-for-the-cameras boulevardiers, as they did Friday.

It will be a long walk through the 21st century before Russia, China and the rest of the non–West arrive at the new world order these nations advocate. They will get there. Some important steps were taken in Beijing and Harbin this week. This is how history’s wheel turns.

By Patrick Lawrence

Published by ScheerPost

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.com