Mary Robinson, Inauguration speech as President of Ireland, December 3, 1990

Dublin University Magazine (1856)

Introduction

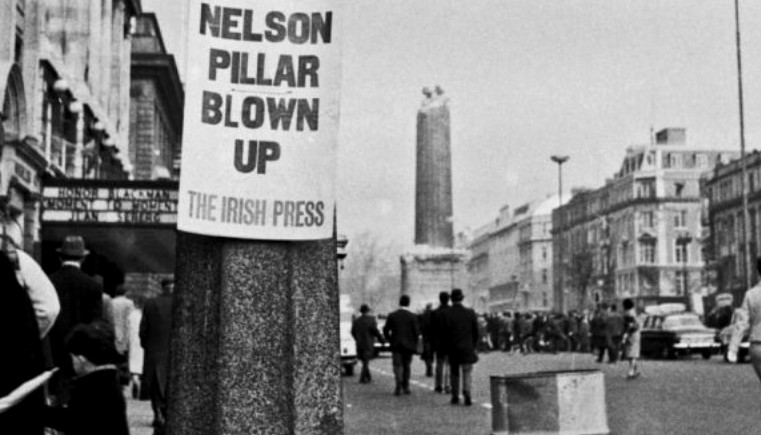

On the night of the 8 March 1966 a massive explosion was heard in the centre of Dublin and Nelson’s Pillar came crashing to the ground in hundreds of tons of rubble. No one was hurt and a stump was all that could be seen of the 157 year old monument. It was not the first time that monuments had been attacked in Ireland and certainly not the last, at least figuratively, with a series of later monuments accruing many derogatory nicknames from the Dublin people.

The recent spate of attacks on monuments in the US and the UK has opened up the debate on the cultural issues they provoke, ranging from those who can’t believe the attacks hadn’t happened sooner to those who see their destruction as mob vandalism.

Here, as everywhere, the public sphere is a highly contested one and not just culturally. For example, when the Irish Republic unilaterally declared independence in 1919, the Dáil Courts (Republican Courts) were set up, creating for the time being, a parallel (and popular) judicial system that frustrated the colonial power by undermining British rule in Ireland, and continued until independence.

Similarly the imposition of British cultural history in Ireland, through its monuments, was resented and these monuments became the focal point for the beginnings of a new public cultural space after independence. By wiping the slate clean, presumably it was thought, it would be possible to create a new progressive space based on Irish revolutionary figures. However, it did not quite work out like that. As in the political sphere, the public sphere remained a highly contested arena with successive conservative governments using different tactics to defer, reject or hinder progressive sculpture in Dublin .

I will look at the fate of some of these British historical monuments and the possibilities for future monuments that would more accurately reflect Irish peoples’ historical struggles for freedom and independence.

‘Removing’ colonial history

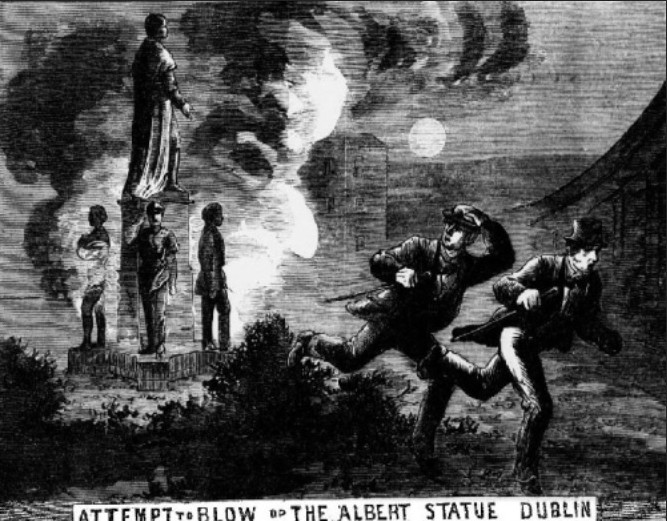

‘Attempt to blow up the Albert Statue, Dublin’ (Illustrated Police News, June 1872)

Prince Albert statue (the husband of Queen Victoria)

This early attempt on a Dublin statue followed controversy which saw the statue’s location being changed from a central position at College Green, according to Donal Fallon, to finding “itself ultimately in the grounds of the Royal Dublin Society. It may surprise some of you to hear the statue is still in Dublin, though now it is inside the grounds of Leinster House.”

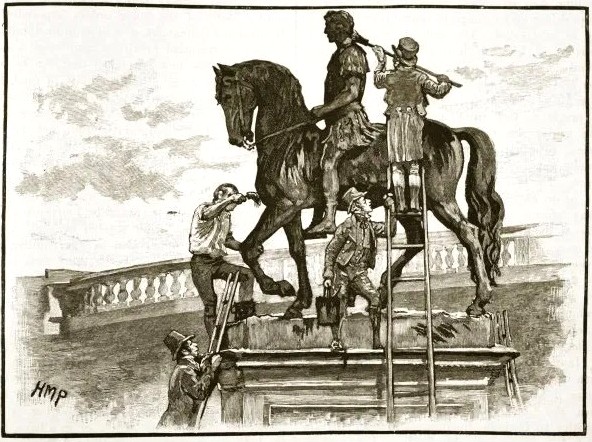

The William of Orange statue was smeared with tar several times

William of Orange (1928)

In 1928 the statue of William of Orange (1701–1928) at College Green (in front of Trinity College) was damaged after an explosion on the anniversary of Armistice Day in 1928 and subsequently removed.

Donal Fallon quotes from the brief commentary on the statue that comes from a book, ‘Ireland In Pictures’, dating from 1898: “This equestrian statue of William II stands in College Green, and has stood there, more or less, since A.D 1701. We say “more or less” because no statue in the world, perhaps, has been subject to so many vicissitudes. It has been insulted, mutilated and blown up so many times, that the original figure, never particularly graceful, is now a battered wreck, pieced and patched together, like an old, worn out garment.”

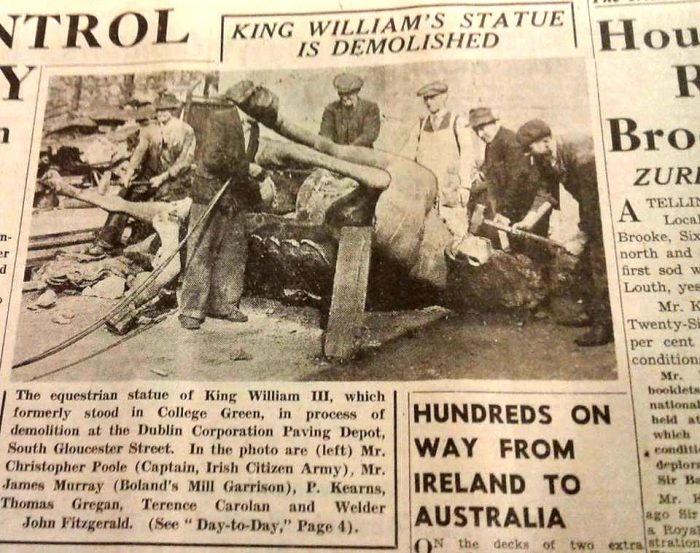

Final demolition of William statue (Irish Press 14 September 1945)

As historian Fin Dwyer writes: “If there was one statue that was not going to survive Irish independence this was it. William of Orange defeated James II at the battle of the Boyne in 1690 and ever since William and his victory has been twisted to suit political circumstances of the day.

His victory had been celebrated by Unionists in the provocative 12th of July Parades in Ireland through the 19th century and he became a despised figure for Irish catholics and nationalists who saw William as a symbol of repression and discrimination. In 1928, the inevitable happened and the statue was blown up. Needless to say it wasn’t rebuilt.”

Victoria statue

‘Young’ Queen Victoria (1934)

According to Professor John A Murphy, UCC: “In August 1849, Queen Victoria witnessed her statue being hoisted on the highest gable of the new Queen’s College, now University College Cork. There it remained until 1934 when it was taken down and replaced by Finbarr, Cork’s patron saint. The Victoria statue was put in storage for some years and then bizarrely buried in what was admittedly UCC’s classiest location, the President’s Garden.”

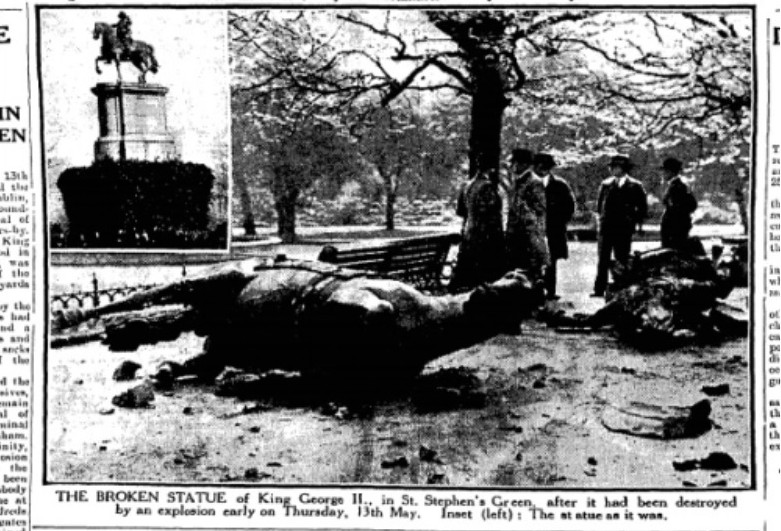

King George II equestrian monument

King George II (1937)

This equestrian monument of King George II in St Stephen’s Green (1758–1937) was blown up on 13 May 1937, the day after the coronation of George VI.

It was unveiled in 1758 and depicted George II in Roman attire. It was placed on a tall pedestal but still ‘the victim of many attacks’.

Statue of Queen Victoria

‘Old’ Queen Victoria (1948)

The statue of Queen Victoria at Leinster House, Kildare Street (1904–1948) was removed in 1948 as part of moves by the Irish State towards declaring a Republic, and eventually shipped to Sydney, Australia in 1987 where it is now on display on the corner of Druitt and George Street in front of the Queen Victoria Building.

The anger towards British colonialism in Ireland could be seen in newspaper reports of the time, for example:

“In 1895, The Nation newspaper noted that Irish migrants in New York had celebrated Victoria’s Jubilee with “the most appropriate celebration”, staging demonstrations and distributing political literature to highlight their view that: “some of the benefits conferred upon Ireland during Victoria’s murderous reign: Died of famine 1,500,000; evicted 3,668,000; expatriated 4,200,000; emigrants who died of ship fever, 57,000; imprisoned under the Coercion Acts, over 3,000; butchered in suppressed public meetings, 300; Coercion Acts, 53; executed for resisting tyranny, 95; died in English dungeons, 270; newspapers suppressed, 12.”

Carlisle statue

George Howard (1956)

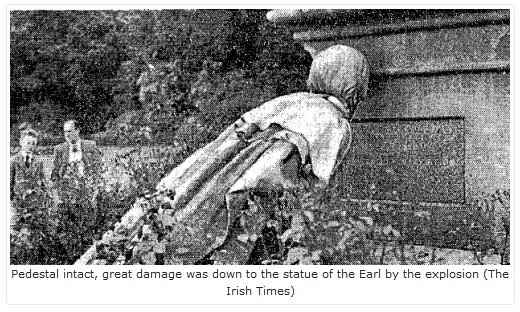

The statue of George Howard (Earl of Carlisle) in the Phoenix Park (1870–1956) was blown off its plinth in an explosion in 1956 and moved to Castle Howard in Yorkshire. The pedestal remains in place as a memorial. George Howard (1802–1864), the 7th Earl of Carlisle, served under Lord Melbourne as Chief Secretary for Ireland between 1835 and 1841.

Gough Monument

Gough Monument (1957)

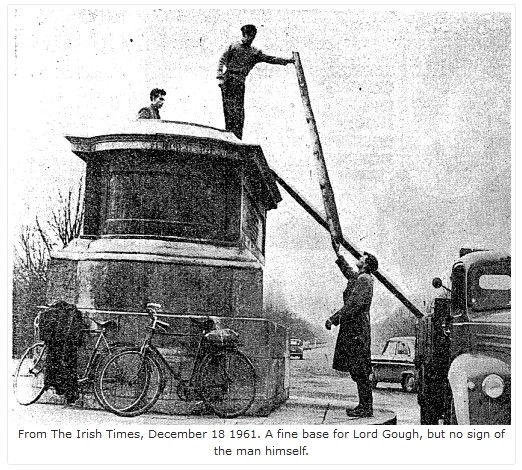

The Gough Monument in the Phoenix Park (1880–1957) was blown up in 1957, it was later restored and re-erected in the grounds of Chillingham Castle, England, in 1990. Field Marshal Hugh Gough, 1st Viscount Gough (1779–1869) was a British Army officer born at Woodstown, Annacotty, Ireland.

Gough’s colonial credentials are impeccable, serving British forces in China, India and South Africa where he “commanded the 2nd Battalion of the 87th (Royal Irish Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot during the Peninsular War. After serving as commander-in-chief of the British forces in China during the First Opium War, he became Commander-in-Chief, India and led the British forces in action against the Marathas defeating them decisively at the conclusion of the Gwalior Campaign and then commanded the troops that defeated the Sikhs during both the First Anglo-Sikh War and the Second Anglo-Sikh War.”

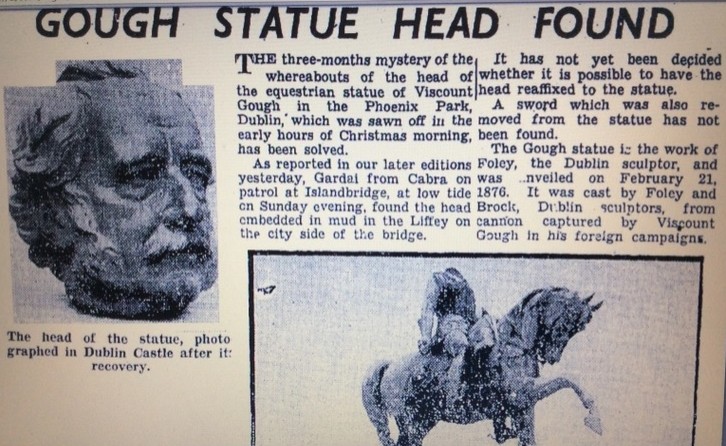

The attack on the Gough Monument demonstrated that being Irish-born was no guarantee of immunity from denunciation and execration. Indeed, the assaults on colonial monuments also became a subject for Irish writers over subsequent decades too. The well-known Irish writer, Myles na gCopaleen, commented on a previous attack on the Gough monument when it was beheaded on Christmas Eve 1944. Writing in his column, Cruiskeen Lawn in The Irish Times in January 1945, he commented:

“Few people will sympathise with this activity; some think it is simply wrong, others do not understand how anybody could think of getting up in the middle of a frosty night in order to saw the head of a metal statue. […] The Gough statue in question was a monstrosity, famous only for the disproportion of the horse’s legs, its present headlessness gives it a grim humour and even if the head is recovered, I urge strongly that no attempt should be made to solder it on.”

The head was eventually found in the River Liffey, the main river running through the centre of Dublin. The fate of the Gough statue is also known because of a poem believed to have been written by another Irish writer, Brendan Behan (though some attribute it to poet Vincent Caprani):

“Neath the horse’s prick, a dynamite stick

Some Gallant hero did place

For the cause of our land, with a light in his hand

Bravely the foe he did face.

Then without showing fear, he kept himself clear

Excepting to blow up the pair

But he nearly went crackers, all he got was the knackers

And made the poor stallion a mare.”

Nelson’s Pillar (1966)

Nelson’s Pillar O’Connell Street (1809–1966) was blown up in 1966 on the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Rising. The head of Nelson’s statue was rescued, and is currently on display in the Dublin City Library and Archive on Pearse Street. Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758–1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy.

His naval victories around Europe, Egypt and the Canaries brought him much fame in Britain and an early death at the age of 47. The remaining stump was blown up by the Irish army to the delight of gathered Dubliners who according to the press“raised a resounding cheer”.

The destruction of the pillar soon became the subject of two songs which both went into the Irish charts. The first called “Nelson’s Farewell” was the first single by The Dubliners and was released in 1966 on the label Transatlantic Records. The gist of the song was that because of the explosion, Nelson, atop the pillar, had been launched into space:

“Oh the Russians and the Yanks, with lunar probes they play

Toora, loora, loora, loora, loo

And I hear the French are trying hard to make up lost headway

Toora, loora, loora, loora, loo

But now the Irish join the race, we have an astronaut in space

Ireland, boys, is now a world power too”

The other song was called “Up Went Nelson”, “set to the tune of “John Brown’s Body” and performed by a group of Belfast schoolteachers, which remained at the top of the Irish charts for eight weeks”:

“One early mornin’ in the year of ’66

A band of Irish laddies were knockin’ up some tricks

They though Horatio Nelson had overstayed a mite

So they helped him on his way with some sticks of gelignite”

Conclusion

Despite the regularly re-engineered cityscape of Dublin, the way was not cleared for a spate of representations of Irish national heroes. What was erected tended to be mythologisations of Irish history (the Children of Lir in the Garden of Remembrance, Cú Chulainn in the GPO: see my 1916 article) as if Irish elites feared the posthumous visages of its bravest and the effect their presence might have on the Dublin populace.

What revolutionary figures that do exist in statue form (Tone, Emmett, Connolly etc) tend to be tucked away in parks or on side streets while the main bourgeois nationalist heroes stand on large plinths on Dublin’s main streets (O’Connell, Parnell etc).

The lack of a major monument on a major street in Dublin commemorating, for example, the Great Hunger or the Seven Signatories of the 1916 Proclamation shows that, despite the decades of resistance to an imposed history, we are still not allowed to commemorate our own.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by countryhere.

The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.