Featured image: A destroyed Vindicator at Ewa field, the victim of one of the smaller attacks on the approach to Pearl Harbor (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

On December 7, 1941 the U.S. naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii was attacked by Japanese forces. President Roosevelt, in his well known Infamy speech delivered on December 8, claimed the attack was “unprovoked” and, on this basis, asked for and received a declaration of war from the U.S. Congress.

But the evidence suggests the attack was not unprovoked. On the contrary, it was carefully and systematically provoked in order to manipulate the U.S. population into joining WWII.

This provocation game, spectacularly successful in 1941, is currently being played with North Korea. The stakes are high.

Many good people are reluctant to look critically at the U.S. role in the Pearl Harbor attacks because they consider FDR a progressive president and because they are appalled at the thought of what might have happened if the U.S. had not joined the war. But they should not allow these considerations to prevent them from examining the Pearl Harbor operation. To give up such examination is to give up the understanding of a key method of manipulating populations.

***

By the late 1930s it was clear to much of the world that war was imminent. British planners worked hard to figure out how Britain could emerge on the winning side of the encounter.

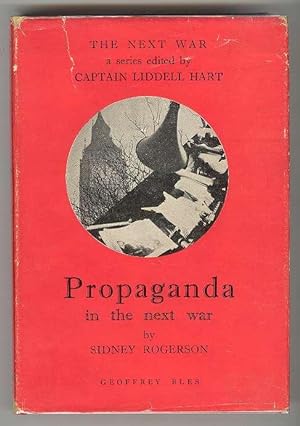

British propaganda expert Sidney Rogerson’s 1938 book, Propaganda in the Next War gives us an important glimpse of British thinking on the eve of war. Rogerson notes that “Japan’s distinction is that she is unpopular,” (p. 142) and he comments that U.S. citizens “are more susceptible than most peoples to mass suggestion–they have been brought up on it.” (p. 146). He is thus able to pose the challenge to the British propaganda community in this way:

“Though we [Britain] are not unfavourably placed, we shall require to do much propaganda to keep the United States benevolently neutral. To persuade her to take our part will be much more difficult, so difficult as to be unlikely to succeed. It will need a definite threat to America, a threat, moreover, which will have to be brought home by propaganda to every citizen, before the republic will again take arms in an external quarrel. The position will naturally be considerably eased if Japan were involved and this might and probably would bring America in without further ado. At any rate, it would be a natural and obvious object of our propagandists to achieve this, just as during the Great War they succeeded in embroiling the United States with Germany.” (p. 148)

Reading Rogerson prepares us for the discovery that the Pearl Harbor operation was a masterful exercise in deceit.

FDR and his top advisors agreed with the British that the U.S. needed to get into the war on Britain’s side, and they felt, or claimed to feel, that conflict between the U.S. and Japan was in any case inevitable. Waiting for war with Japan to break out spontaneously was, they felt, a poor idea. But it was also a poor idea to have the U.S. fire the first shot: Japan had to appear as the aggressor.

This was the only way to put the U.S. population in the mood for war. The majority of U.S. citizens opposed entering WWII (Stinnett, p. 7) just as they had opposed entering WWI in 1914. Therefore it was decided to goad the Japanese. As U.S. Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, put it shortly before the Pearl Harbor attack: “The question was how we should maneuver them into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves.” (Stinnett, p. 178)

Robert Stinnett served in the U.S. Navy in WWII. He spent 17 years researching the Pearl Harbor events before bringing out, in 2000, his book, Day of Deceit: The Truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor. I find his argument, based on solid documentary evidence unearthed through Freedom of Information requests, convincing.

Stinnett names eight steps of provocation proposed on October 7, 1940 by Lieutenant Commander Arthur McCollum. The list includes instituting a complete embargo on trade with Japan (Stinnett, p. 8). Subsequent to McCollum’s list, it was decided also to institute “the deliberate deployment of American warships within or adjacent to the territorial waters of Japan” (Stinnett, p. 9).

Stinnett says,

“Throughout 1941, it seems, provoking Japan into an overt act of war was the principal policy that guided FDR’s actions toward Japan” (Stinnett, p. 9).

He further claims that McCollum’s specific suggestions were followed closely (Stinnett, p. 9).

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signing declaration of war against Imperial Japan on December 8, 1941 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In 1941 the U.S. leadership put into effect the complete embargo McCollum had proposed. This included cutting off Japan’s supply of oil, a move that would have made Japan’s continued participation in the war, and even its existence as an industrial nation, impossible. As one commentator put it:

“We cut off their money, their fuel and trade. We were just tightening the screws on the Japanese. They could see no way of getting out except going to war” (Stinnett, p. 121).

The Japanese response was predictable. In their declaration of war against the United States (and Britain), published directly after the Pearl Harbor attack, they said:

“They have obstructed by every means Our peaceful commerce and finally resorted to a direct severance of economic relations, menacing gravely the existence of Our Empire…This trend of affairs, would, if left unchecked, not only nullify Our Empire’s efforts of many years for the sake of the stabilization of East Asia, but also endanger the very existence of Our nation.”

By the time Japan decided on its aggressive response U.S. intelligence had cracked the vital Japanese communication codes, both diplomatic and military (Stinnett, xiv and throughout), and was able to track closely Japanese vessels as they began their movements toward Pearl Harbor. The attack was permitted to proceed without obstruction.

The day after December 7, 1941, after listening to FDR’s Infamy speech, and believing his claim that the attacks had been unprovoked, Congress duly passed a declaration of war against Japan. Because of treaties then in place, the U.S. was at war with all the Axis powers.

Are we to believe that this provocation game, so useful to U.S. planners those many decades ago, now gathers dust on the shelf? On the contrary, U.S. strategy today requires it, and its proponents are in some cases surprisingly frank about this. For example, in the publication, Which Path to Persia?, authored by strategists at the Saban Centre (housed in the Brookings Institution), we find the following argument:

(a) Any major, overt military action against Iran by the U.S. will be very unpopular (this was in 2009) internationally and domestically unless it is seen as a response to Iranian aggression.

(b) Waiting for the Iranians to carry out such an act may mean waiting forever, because Iran avoids such actions.

(c) It may, therefore, be necessary to goad Iran into such an action—especially if the aim is an invasion of Iran with regime change as in the Iraq case.

(d) The more violent the Iranian response to U.S. goading, the better. All military options are at that point easy to pursue.

The authors note:

“it would be far more preferable if the United States could cite an Iranian provocation as justification for the airstrikes before launching them. Clearly, the more outrageous, the more deadly, and the more unprovoked the Iranian action, the better off the United States would be. Of course, it would be very difficult for the United States to goad Iran into such a provocation without the rest of the world recognizing this game, which would then undermine it. (One method that would have some possibility of success would be to ratchet up covert regime change efforts in the hope that Tehran would retaliate overtly, or even semi-overtly, which could then be portrayed as an unprovoked act of Iranian aggression.)” (pp. 84-85)

Later they return to the theme of covert regime change as deliberate provocation:

“Indeed, for this same reason, efforts to promote regime change in Iran might be intended by the U.S. government as deliberate provocations to try to goad the Iranians into an excessive response that might then justify an American invasion.” (p. 150)

The dream of these authors is an attack on the U.S. similar to the assaults of 9/11 (p. 66). Their problem is how to bring this about. If they could get an Iranian assault, they feel, U.S. forces could then do whatever they wanted to do to Iran without resistance from either the U.S. domestic population or the international community.

This, then, is what the “game” looks like among certain U.S. strategic thinkers today. As for citizens of the relevant states–democratic or otherwise–we are outside the game and are supposed to remain in a state of political unconsciousness. If we recognize the game, we undermine it.

At this moment, it seems to me that the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea) is even more vulnerable to the provocation game than Iran. The game, in fact, is already in progress.

We have seen several means employed to provoke the DPRK. The most blatant are insults and threats. For example, U.S. President Donald Trump and U.S. Secretary of Defense Mattis have threatened to commit the crime of genocide against the DPRK.

Screengrab from independent.co.uk

Two further actions bring us unsavoury reminders of the provocative acts of the Pearl Harbor operation.

(a) Military maneuvers in the region

To antagonize its diminutive opponent (far smaller, in both area and population, than the state of California), the U.S. led a series of extremely provocative military exercises near the DPRK. The exercises included large numbers of weapons systems, some of them nuclear capable–a clear threat of not only aggressive action but nuclear attack.

(b) Oil embargo

In addition to escalating general economic sanctions strangling the DPRK economy, the U.S. has tried to cut off the DPRK’s entire supply of oil. The DPRK has no significant oil production of its own and relies on China and Russia for its oil, without which it cannot survive as an industrialized country. Only the noncooperation of China and Russia has forced the U.S. to accept, for the moment, a less draconian move. With UN Security Council resolution 2375, passed on September 11, 2017, the DPRK has lost about 30% of its oil imports.

The cynicism of the UN Security Council in passing UNSC 2375 is staggering. How can the five permanent members of this body refer to the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), which they piously do in the text of 2375, as a basis for the harsh treatment of the DPRK? It is true that this treaty seeks to halt the spread of nuclear weapons to states that do not have them. But it also seeks to get rid of the nuclear weapons already possessed by nuclear states. Written in 1968, the NPT says:

“Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

Far from doing this, the permanent members of the Security Council continue to guard their nuclear weapons and to resist attempts to get rid of them. All five of the nuclear powers who happen to be the permanent members of the UN Security Council have refused to sign the recent Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

As long as the Security Council’s permanent members continue to ignore the NPT’s call for nuclear disarmament, and as long as they likewise refuse other treaties calling on them to get rid of their nuclear weapons, they have no credibility when they insist that other states (the particular ones they designate as “rogue”) remain nuclear weapons-free. If the NPT disallows the spread of nuclear weapons while permitting existing nuclear powers to hold on to their nuclear weapons, it simply becomes a fancy way of maintaining the exclusive Nuclear Club.

The NPT also states that

“in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, States must refrain in their international relations from the threat of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.”

Instead, we have the U.S., which authored UNSC 2375, threatening the most serious crimes it is possible to commit, including genocide, against the DPRK.

To be clear, I do not approve of the acquisition of nuclear weapons by any state under any circumstances. I have spent my adult life opposing nuclearism. I do not rejoice in the nuclear weapons of the DPRK. But that government is not going to give up its nuclear program voluntarily as long as it feels under existential threat. What DPRK leaders say publicly–we need a deterrent against U.S. aggression–is the same thing their diplomats have said to me privately. And how can the permanent members of the Security Council reject this argument when every one of them believes in nuclear deterrence? Which one of them can claim to be under more threat than the DPRK?

The sad fact is that as long as the so-called “great powers” continue to use treaties such as the NPT to get what they want, while denying other states equal rights, nuclear proliferation will be extremely difficult to prevent.

I have no magical solution to the current crisis, but it seems to me that the Security Council is violating the UN Charter, which it has no authority to do, and is acting to prevent a peaceful outcome.

If I had a global platform from which to address the world I would say the following.

(a) To the leaders of the DPRK:

Please do not play the provocation game. I know you are not insane and therefore I know you will not carry out a Pearl Harbor attack on the U.S. or its allies. But responding, as you have in some instances, with threats and harsh rhetoric is dangerous and cannot possibly benefit you. In fact, such responses make it possible for U.S. leaders to turn any accident or international incident against you. They may even fabricate an incident (create a false flag attack on themselves), in which case every threat you have ever made will be quoted to prove to the world that you are the guilty party.

(b) To China and Russia:

I understand why you do not want to risk the survival of your states and your populations for the protection of the little DPRK, which you no doubt regard as something of a loose cannon. But remember that giving in to U.S. bullying is like giving in to the demands of a violent hostage-taker. No good is likely to come of it in the long run.

(c) To the United Nations as a whole:

Only by addressing the genuine and legitimate security concerns of the DPRK will you be likely to achieve a peaceful outcome to the current crisis. If you believe in your own organization, its purpose and Charter, you will not cooperate with the imperial policies of those members who, to the grief of the world, are installed in positions of privilege in the Security Council.

(d) To the people of the world:

Remember Pearl Harbor. That is, understand the provocation game. Recognize it whenever it is played. Undermine it.

By Prof. Graeme McQueen, Global Research

This article was first published by GR

The 21st Century