Organization of American States (OAS) election monitors published a “final report” on December 4—22 days later than promised—on Bolivia’s October 20 presidential election, won by President Evo Morales. The tardy release of the final report contrasted sharply with the way the OAS rushed to impugn the election the day after it took place.

Only three days after the election, the OAS published a preliminary report that reiterated its negative assessment.

On November 10, it then issued a press release saying the election should be annulled. In these statements, the OAS claimed that the change in Morales’ lead in the last 16% of the vote count was “drastic,” “inexplicable” and “hard to explain.”

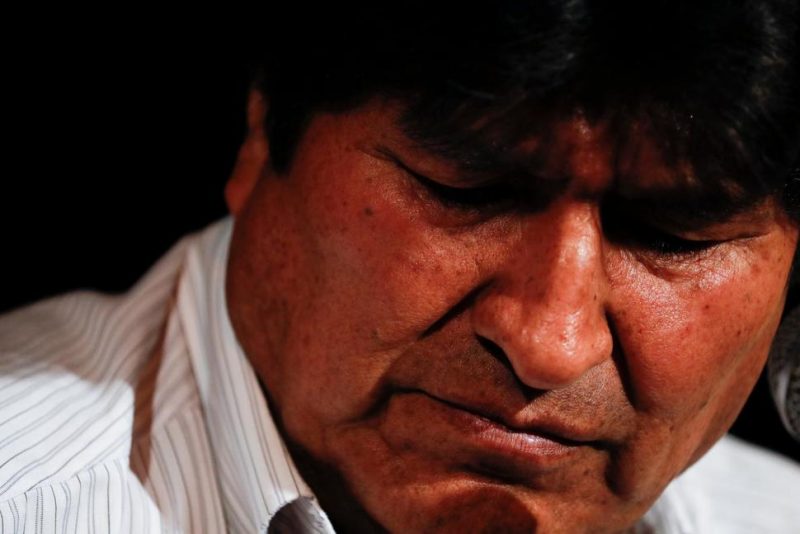

By November 11, mutinous generals and police (combined with armed opposition vigilantes) had driven Morales into exile in Mexico. He and his vice president barely escaped with their lives. Morales’ house was ransacked. Since then, the security forces that refused to protect the democratically elected government have killed some 32 people to prop up the coup-installed dictatorship.

When the final OAS report on the election was belatedly released on December 4, a Reuters article (12/4/19) about it ran with the headline “Bolivia Election Rigging in Favor of Morales Was ‘Overwhelming’: OAS Final Report.” The only critic of the OAS report mentioned in the article was Morales himself.

But the OAS had come under heavy fire from US-based economists and statisticians ever since it began impugning the election on October 21. It’s impossible to learn that fact in 114 Reuters articles about Bolivia since the October 20 election. None even mentions the extensive technical criticism the OAS has received.

The criticism should have received much more than a discrete mention in an article or two, but in over 100 articles, the London-based wire service didn’t even provide that.

On December 12, I sent an email to several Reuters journalists and editors who have produced articles on Bolivia since October 20. I asked why that criticism has been completely ignored. None have replied.

On October 23, the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) issued a press release asking that the OAS retract its comments about the election.

On November 8, the think tank published a paper rebutting the OAS. Mark Weisbrot, co-founder of CEPR, followed up with an op-ed in MarketWatch (11/19/19) that said the OAS “lied at least three times: in the first press release, the preliminary report and the preliminary audit.”

On November 25, four members of the US Congress asked the OAS to respond to very specific questions raised by CEPR.

On December 2, the Guardian published a letter signed by 98 economists and statisticians asking the OAS to “to retract its misleading statements about the election, which have contributed to the political conflict and served as one of the most-used ‘justifications’ for the military coup.” Did Reuters really miss all of this?

Not ‘hard to explain’

The graph below substantiates much of CEPR’s case against the OAS. It also exposes common deceptions in Reuters reporting.

The light blue dots are a plot of Evo Morales’ lead over his nearest rival against the percentage of the vote counted by the unofficial “quick count.” The dark blue dots do the same for Morales’ political party (MAS) in legislative elections.

Following OAS recommendations, Bolivia has a “quick count” (TREP) that keeps the public updated, and a slower, legally binding count (the computo). The legally binding count was never interrupted. The TREP stopped being published at 84% of the count, but the electoral authorities never committed to publishing it past the 80% mark.

Morales’ lead increased steadily as votes from the more pro-MAS areas came in. When the TREP was stopped at 84%, his lead was 7.9 points. By the time all the votes were counted, the official tally had him just over 10 points ahead.

The 10-point margin was crucial because to avoid a second round, Morales needed at least 40% of the vote and a 10-point lead over his nearest rival. Morales received 47% of the vote, which was in line with what pre-election polls predicted.

The two-point lead increase in the last 16% of the vote count was not “drastic”: It was consistent with a gradual increase in his lead throughout the election. It was also not “hard to explain”; CEPR’s precinct-level analysis of where the final votes were coming from showed it was quite predictable.

Parroting the OAS line, Reuters articles were deceptive. One article (11/6/19) stated the vote was “marred by a near 24-hour halt in the count, which, when resumed, showed a sharp and unexplained shift in Morales’ favor.”

Others (11/4/19, 11/6/19, 11/6/19, 11/8/19, 11/8/19, 11/10/19) used very similar language describing a “halt” or “pause” to “the count”—thereby obscuring that there were two counts, and that the legally binding one was never halted.

Another deception in many articles was neglecting to tell readers that Morales already had a 7.9 point lead when the quick count was stopped.

For example, one Reuters article (11/10/19) ran with the headline “How Did Bolivia End Up in Democratic Crisis?” It vaguely stated that the election seemed to be “heading to a second round” but after an (imaginary) “pause in the count,” Morales had a “10-point-plus lead.”

Notice how it’s left to the reader to imagine by how much Morales’ lead increased after the quick count was stopped.

And Reuters also conveyed nothing about the trend. See the graph above. Morales did not have a constant 7.9 point lead for much of the election that suddenly jumped at the end. Nor was his lead declining when the quick count was stopped. The lead had been steadily increasing through almost the entire vote count.

The trend in the last 16% of the count was also extremely similar to what took place in a 2016 referendum on term limits that Morales narrowly lost—an election result viewed as sacrosanct by Morales’ opponents. In that election, there was also about a 2-point increase in the share of the vote for Morales in the last 16% of the vote.

Ducking debate

The Mexican government had agreed to let Jake Johnston of CEPR respond to the OAS final report at the permanent council meeting on December 12. The OAS refused to allow it. Johnston would have presented CEPR’s preliminary response to the 100-page final report.

Reuters has thus far said nothing about the OAS ducking its main critics.

Of course, to do that, Reuters would have to break its silence on the entire debate.

Among other things, CEPR observed that the OAS final report doubled down on its false claim of a “drastic” and “inexplicable” change in Morales’ lead; that the report focused on a “hidden server” and other “vulnerabilities” in the electoral system, but “conceals or fails to provide information” showing that those vulnerabilities impacted the results; that 226 tally sheets the report claimed prove “deliberate manipulation” overwhelmingly point to a “well-known phenomenon: In rural areas and smaller voting centers, it is not uncommon for one person to fill in the tally sheet, and then have the individuals each sign it.”

The OAS final report also shifted to claiming that manipulation occurred in the last 5% of the count, but Morales received a smaller share of the votes cast in the last 5% of the count compared to the previous 5%.

Additionally, CEPR argued, his share of the vote in the last 5% was also “entirely predictable based on the prior trends seen in the geographic areas from where these final votes came.”

Incidentally, David Rosnick, also with CEPR, very recently refuted a separate statistical analysis that apologists for the coup have been citing—mainly on social media, since in outlets like Reuters, there is no debate to be followed at all.

OAS’s unmentionables

The bureaucracy of the OAS is based in Washington and is about 60% funded by the US government. In 114 articles, Reuters never mentioned this either. If the OAS were based in Caracas and 60% funded by Venezuela, do you think that would have been mentioned a few times?

OAS “monitoring” of elections in Haiti in 2000, and again in 2011, was used to help Washington disgracefully overrule Haitian voters. The current OAS general secretary, Luis Almagro, recently blamed Cuba and cash-strapped Venezuela for huge protests against neoliberal policies in US-allied states: Colombia, Chile and Ecuador.

Morales, a close ally of Venezuela and Cuba, was gambling when he agreed to let the OAS monitor the election—especially given that the member states of the OAS have shifted towards right-wing, pro-US governments, giving much less of a counterweight to Washington’s influence within the OAS bureaucracy than in previous years.

But not allowing OAS monitors would also have been dangerous, providing a different pretext for Washington and compliant outlets like Reuters to impugn the election. That could easily have resulted in the US imposing crippling economic sanctions—whose impact Reuters could also be relied on to bury (FAIR, 6/14/19).

It’s far more likely that Bolivia’s election was clean, and that the OAS audit was dirty, than the other way around. Unprincipled journalism from one of the world’s major news agencies has hidden that from a lot of people.

Joe Emersberger is a writer based in Canada whose work has appeared in Telesur English, ZNet and CounterPunch.

This article was originally published by “Fair“

The 21st Century