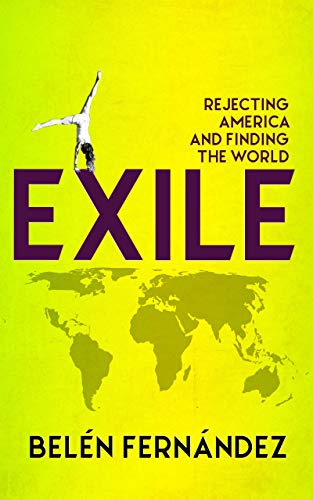

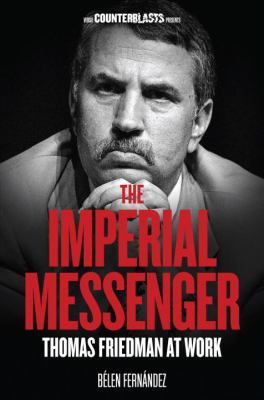

Fernandez’s second book could be called The imperial messenger: Thomas Friedman at work Part II, or This is Not a Travel Book. The subject of her first book delightfully keeps popping up at conferences, interviewing American puppets, his spirit haunting her from the New York Times opeds exhorting Africans to tend their gardens, saluting Colombian ex-president Uribe.*

Her observations are often laced with strychnine, since, for all her revulsion at the empire, she can’t avoid its footprint. It is everywhere, often ridiculous, all too often lethal, tragic,

the global superpower that has specialized in making much of the planet an unfit abode for its inhabitants via a combination of perennial war, environmental despoliation, and punitive economic policies resulting in mass migration. Despite being founded on slavery and the genocide of Native Americans, it presents itself as the global model for greatness—a position that is unilaterally interpreted as a carte blanche to bomb, invade, and otherwise enlighten the rest of the world as it sees fit.

Every few pages, a lightbulb moment.

My subtext here: and produced a miniature replica called Israel, which has the same pedigree.

Fernandez rubs Uncle Sam’s nose in its faux history, where the experiences of its founding victims are cast as free-standing tragedies that allude in no way whatsoever to the putrid core of the US enterprise, while the more contemporary slaughter-fests in Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Vietnam, Iraq, and beyond are just Things That Had to Be Done.

This is not a travel book for the faint-hearted, or even a guidebook for where to go, what to do. This is hardcore, down-dirty travel and travel writing. A personal Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. A new and powerful form of nonfiction, a primer.

Almost a companion volume to Linh Dinh’s Postcards from the End of America (2017), by a Vietnamese American, travelling through the US mostly by bus, a view of the beast from someone from the empire’s periphery.

Lindh exposes the hopelessness of the actors at the empire’s heart, imperialism’s legacy in the centre. White, born-in-America Fernandez can’t stomach the centre and defiantly lives and writes abroad.

Fernandez keeps us going with lots of humour, and leaves the reader impressed with and fond of most of her characters, all full of life, never down and out, unlike most of Linh’s, who are living a losing battle. (Linh decamped to a village in Vietnam shortly after finishing his book, like Fernandez, unable to deal with the daily insanity of life in the heart of the beast.)

Global warming has taken all the fun out of the insane luxury, that westerners enjoy, of flitting around the globe. Belen does acknowledge “flying around for 80-something hours polluting the planet” is not a sustainable activity, and warns that a billion involuntary refugees will soon be fleeing flooding and drought brought on by this irresponsible flying mania.

So while some eco-friendlier peregrinatory adjustments are no doubt in order on my part, so is the overthrow of the entire putrid system itself.

Lots of telling quotes that are like vaccines or, for those already bitten, antibiotics. In 1967, Martin Luther King, Jr. denounced the US government as“ the greatest purveyor of violence in the world,” with the Vietnam War “the symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit.” Indeed, he lamented, the US was “on the side of the wealthy, and the secure, while we create a hell for the poor.”

Fernandez fled to the University of Rome for her junior year abroad from Columbia. When she returned,

My homeland resembled a large-scale lab experiment on how to best crush the human soul. The rigidity and joylessness of the place were more glaringly obvious after a year in a Roman neighborhood where everything closed for four hours in the middle of the day to allow for leisurely gorging and naptime. The self-assured grace with which Italians seemed to move through the universe

made her realize she couldn’t stay in the beast, with its

manic air-conditioning and other joys of an alienated society, where capitalism was tied up with the criminalization and pathologization of normal human behavior that left the criminally diseased system itself untouched.

No, this is not a travel book. It is more like a volume of high adrenaline, funny, but wise meditations on the desperate state of a floundering world. And while Belen lives in exile from the beast, her observations on it are compelling. School shootings—one of those phenomena that is somehow magically absent from many of the Inferior Countries of the globe. Hey, why didn’t I notice that?

Or, that a Trump was not a fluke. A mere glance at the national track record of bipartisan support for eternal war, bigotry, American exceptionalism, and the deification of money suggests that America had all the right preexisting conditions and then some.

Belen, the female, is no frightened, cowering second class citizen. She teams up with Amelia, a Polish American with wanderlust, when taking an ESL diploma in Crete (which she has never used), and their hitchhiking expeditions enabled us to confirm that, while the planet may have been going to hell, there were still some damn fine people on it.

I usually warn women against travelling rough. Alone, never. But two women, dressed like men, at least one of them tough as nails, worked like a charm for Belen and Amelia, whose parents opted to abandon the domain of the Warsaw Pact and check out what life was like in places where the basic necessities of survival were not free.

You can piggyback on male gallantry/ chauvinism, which is still the norm in the third world and ex-socialist bloc, getting easy rides, a visa (time after time) on the Syrian border (Americans not allowed), a border guard even commandeering a hapless driver with instructions to take the ladies to the next town.

Her mordant sense of human, makes the reader feel for her, fated to be born to the Earth’s enemy tribe, a victim (along with all Americans), but she qualifies her scathing criticism of the US with sympathy for the plight of the real victims — blacks, Iraqis, wherevers. The need to be in

continuous motion is, it seems, some sort of severe form of commitment-phobia combined with a desire to be simultaneously everywhere and accompanied by an intense envy of human populations that actually possess a culture. The only entity currently on the definitive no-go list for travel or transit is the homeland itself—the great irony of course being that my ease of global movement is thanks largely to a passport bestowed by that very same land.

But she uses this passport, a grotesque privilege in an epoch characterized by mass forced displacement to telling effect, edifying the reader, and where possible, aiding her travel acquaintances.

She points out ironies/ contradictions: NAFTA bankrupted a third of Mexican farmers who had to abandon their land because of ‘free trade’, and now desperately try to get into the US. Capital can float between nations with all the ease of a monarch butterfly, so logically labour too should be mobile. But ‘free trade’ is free only for capital. Labour is expendable.

Or Beirut, which appeared in the 1876 Baedeker guide Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travellers—which if nothing else should be of interest to contemporary inhabitants of the world who claim there was never any such thing as Palestine. Polite understatement is the best way to use your pen as a weapon. Nice one, Belen.

It’s not long before Thomas Friedman’s snout appears, Belen’s bete noire. Her other pen-sword technique is to let people betray their assholery themselves. When Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982, Friedman notes, Israeli soldiers ogled the shiksas: “This was not the Sinai, filled with cross-eyed Bedouins and shoeless Egyptian soldiers.”

Edward Said retorted, lambasting Friedman for “the comic philistinism of [his] ideas,” his embrace of “the purest Orientalism,” and his peddling of “moronic and hopelessly false dictum[s].”

I love a writer who puts all the best stuff in footnotes (realizing they are distractions or just because the article refuses to come in under 1500 words as it is, i.e., this paragraph in this article).

Friedman’s lies and distorts in the interests of Zionism and Capitalism are too telling to leave out, though they have a place in footnotes. Friedman wrote about two supposed secret Hezbollah bases in Lebanon, the tiny villages of Muhaybib and Shaqra.

The former contained no fewer than “nine arms depots, five rocket-launching sites, four infantry positions, signs of three underground tunnels, three anti-tank positions and, in the very center of the village, a Hezbollah command post.”

Shaqra, population 4,000, was meanwhile home to “about 400 military sites and facilities belonging to Hezbollah.”

The article specifies that the Times’ Anne Barnard (who mocked Lebanese women with dangerously spike heels) “contributed reporting from Beirut”—although it’s unclear why she couldn’t have made the two-hour drive to the villages in question for a quick glance around. I myself, though in possession of a budget nowhere comparable to that of the Times, managed to rent a cheap car and visit both villages, where I did not see any Hezbollah command posts but did see plenty of schoolchildren, old people, houses, farms, a colorful establishment offering “Botox filling,” a place called Magic Land, a painting of Che Guevara, and a graffito reading “THUG LIFE.”

I’ve always been suspect of the trendy, sometimes funny, VICE news, and similarly vaguely lefty publications which tongue-in-cheek commend the sleazy nightlife of Beirut or wherever. A piece in VICE about Lebanon, “Fighting for the Right to Party in Beirut,” tsk-tsks that “bars offer coke-fueled benders down the street from Hezbollah headquarters.” Belen’s subtext:

Of course, the glorification of élite excess is nothing new in a global panorama in which shameless and all-encompassing materialism directly serves the interests of the powers that be. It is in this context that we must view the encouragement and applause for Arab populations sufficiently trained in Western-style decadence so as not to pose too much of a threat to the world order.

Rather than sound bytes, Belen distills history into sound bullets: referring to Israel’s 2006 assault—not to be confused with Israel’s 1978, 1982, 1993, or 1996 assaults, or its 22-year occupation of the southern part of the country.

Another tidbit that struck me: Her Lebanese (sorry, Palestinian-living-his-entire-life-in-Lebanon-but-without citizenship, so no health care, pension, etc.) friend Hassan almost made it to Cuba (long, fascinating story)—one of the few places in the world that welcomes the Lebanese travel document for Palestinian refugees. Wow.

What would we do without Cuba, that island of sanity in a mad world?

Belen benefited from Cuban doctors in Venezuela, but doesn’t dwell on her travels in Cuba, no doubt because there’s no pressing need to share pleasant (or frustrating) experiences in a society where the beast was slain (so far).

Belen is a writer on the move, not just physically, but as a world citizen, fighting the good fight. Bringing us on board.

I’m halfway through (it’s too chock full of good stuff to whip through at one sitting), and looking for the next juicy tidbit. Honduras was horrifying, disgusting. You want to burn a US flag after reading, but the fascinating bits kept you turning the page. The military carried out an open coup in 2009, but the US couldn’t declare it a coup or it would have had to cut arms sales, so it became

“the Coup-Type Thing in Honduras,” and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton set about “strategiz[ing] on a plan to restore order in [the country] and ensure that free and fair elections could be held quickly and legitimately, which would render the question of Zelaya [the good guy] moot and give the Honduran people a chance to choose their own future.”

Yes, the legitimate president is overthrown in a coup (be thankful he wasn’t tortured and murdered), so instead of gently pushing the thugs to reinstate him, just hold new (rigged) elections so the Honduran people have a chance to choose their own future. This is what [Clinton] wrote in her 2014 memoir Hard Choices, in a passage mysteriously excised from the paperback edition the following year. ‘Stop complaining. Move on already.’

It struck me reading this, that there are two choices in elections under the Monroe Doctrine: elect someone the US likes and the US won’t subvert you. If you don’t, then expect a/ a coup, or b/ boycott, sanctions and divestment + contras as in Nicaragua. The US can provide all the Benjamins and weapons to the School-of-the-Americas trained local thugs.

Correction: School of the Americas changed its now toxic name to Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation. Good move: make the name so incomprehensible and tendentious that it will be hard to remember and therefore hard to criticize.

A delightful romantic moment: Belen is ambushed in Mexico by a truly crazy pair, Al Giordano, an Gene Sharp/ Mahatma Gandhi nonviolence activist, editor of Narco News, and his sidekick Marovic, a Serbian who helped Giordano overthrow Milosevic in 2002, both backed by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, an outfit run by a grotesquely wealthy American investor and other concerned members of the global populace. He told her she should stop criticizing Israel in her Narco News articles, proposing she come to live with him in Mexico city.

As of 2018, cursory internet research revealed that Giordano had been slammed with sexual harassment allegations and that Marović had relocated to Kenya, where he was the proprietor of an unused blog titled Retired Revolutionary and a devoted Instagrammer of nature and wildlife photos. She diligently sources this ‘information’ to The Narco News Bulletin, “A Revolution Is Like ‘Good Sex’: The Ivan Marovic Story Is Coming to a Street Theater Near You.”

What is revolutionary about Belen’s style is that she is quoting such ‘facts’, or rather factoids, created in virtual reality. They are both hilarious and an expose of the monstrousness of imperialism, how it creates nonsense, nonsensical organizations, nonsensical information, which we can access from anywhere. Benen writes about the facts that she has shaped/ experienced, sometimes betraying a confidence, as with Giordano, though it is hard to feel sorry for the troll. Being a talented writer, Benen deftly uses her pen as a very sharp sword. The writer feels like s/he is eavesdropping. Benen doesn’t suffer fools. Good on her.

Another plus in Exile is we meet the local heroes. We all know of Jose Marti and Simon Bolivar, the great 19th century defenders of democracy and independence. In Honduras, Belen befriends Palencia, a musician and composer with a vision of creating a rock opera about the life and work of Francisco Morazán, nineteenth-century Honduran hero, liberator, and “public enemy of political and religious mediocrity.” We are reminded of a wonderful era of liberation struggles in Latin American and Europe.

But, I suddenly realized, not in North America. Why? What was America doing in the 19th century? Drowning in genocide, both against the natives and the slaves, and fighting a civil war to fashion the engine of empire. So American was never ‘liberated’, though it was not in the least ‘free’. It struck me: Belen is one of a new breed of travel writing, documenting the crumbling of empire in all its savagery, and our struggle against it.

By Eric Walberg,

http://ericwalberg.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=733:review-belen-fernandez-exile-rejecting-america-and-finding-the-world&catid=44:books-of-interest&Itemid=97

The 21st Century

xxx * Labelled by the Defense Intelligence Agency as narco-trafficker, lauded by Friedman for his struggle against narco-traffickers.