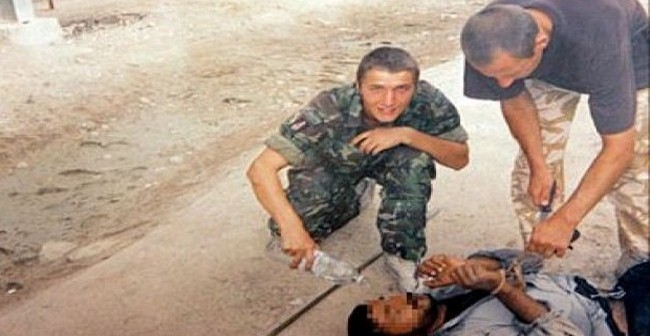

A US soldier and a Vietnamese interpreter use the “waterboarding” technique on a Viet Cong suspect near Da Nang, South Vietnam, January 17, 1968.

The Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1791, prohibits the use of ‘cruel and unusual punishments’. General Order No. 100 (the Lieber Code of 1863) declares that ‘military necessity does not admit of cruelty’ and explicitly bars American soldiers from torture.

The UN Convention Against Torture, which the United States signed in 1988, stipulates an absolute ban on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading punishments.

Yet, as W. Fitzhugh Brundage amply demonstrates in Civilizing Torture: An American tradition, the United States has used torture at home and abroad for centuries.

Physical and psychological torment helped subjugate indigenous and enslaved populations, underpinned the formation of the carceral state, and has long been an instrument in America’s military adventures, particularly in the developing world.

Yet notions of national exceptionalism have led many Americans to insist that the United States is a ‘unique nation with uniquely humane laws and principles’.

Thus, despite international revulsion at the horrors inflicted by American soldiers at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, President George W. Bush still maintained that ‘any activity we conduct, is within the law. We do not torture.’

Although the material in Civilizing Torture is distressing, Brundage’s approach is restrained. Acts of extreme cruelty are a necessary element for his argument, but this is neither an exhaustive catalogue of bodily humiliations, nor a partisan polemic.

The book ranges from the earliest moments of exploration and colonisation in the 1500s and 1600s, to the War on Terror in the 2000s. Case studies are included because, at the time they occurred, they triggered public discussion about whether certain practices or behaviours were torturous.

By focusing on these debates, Brundage demonstrates the long history of torture in the United States while exploring the ways that torture has been discursively justified. The public nature of the evidence base also hammers home one of his core contentions: ‘torture in the United States has been in plain sight, at least for those who have looked for it.’

Some examples, such as the use of the ‘water cure’ in the Philippines in the early 1900s, or the rape, abuse, and murder of civilians in Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, the torture and ritual humiliation of prisoners as part of the War on Terror in the early 2000s, are well known.

Brundage’s contribution is to methodically ground these notorious events in the broader historical context, vividly undercutting official claims that heinous acts are the work of a ‘few bad apples’.

A particularly fascinating thread is the focus on physical and psychological coercion in the nation’s prisons and police stations.

In the new-model penitentiaries of the early 1800s, ‘bodily suffering’ was often seen as an instrumental means of compelling obedience, crucial if inmates were to be rehabilitated.

From the late 1800s to the 1930s, a modernising police force relied on extreme forms of violence (the so-called ‘third degree’) to extract confessions.

Although the Supreme Court eventually ruled these excesses to be in violation of the Constitution, police torture did not completely disappear.

In the 1970s and 1980s, some Chicago officers openly terrorised African-American suspects, deploying the techniques they had learnt as soldiers in Vietnam.

This element of the book is urgent and timely, vital to understanding the dangers inherent in the dramatic growth of the prison–industrial complex, as well as the long history of police brutality that fuels contemporary movements such as Black Lives Matter.

An American soldier, aided by South Vietnamese soldiers, interrogates a suspected Viet Cong insurgent, undated.

Throughout, Brundage offers important insights into how extreme acts of physical and psychological violence are reframed and redefined. In almost every instance, defenders of torturous practices present American actions as falling on the acceptable side of state violence.

As one CIA agent mused about the methods used to interrogate Vietnamese communist prisoners, ‘Were they tortured? It depends on what you call torture.’

At various points in US history, hangings, suffocation, stress positions, beatings, burnings, electrocution, waterboarding, sustained solitary confinement, and profoundly disorienting ‘brain warfare’ were all treated as legitimate techniques for the use of a modern, civilised society.

This long-running renegotiation of what exactly constitutes torture has also helped Americans maintain that ‘torture is something done by other people elsewhere’ (whether that be Catholics during the Spanish Inquisition, Native Americans, Filipino and Vietnamese nationalists, communists, or terrorists).

When American colonists, prison officers, slave owners, soldiers, or police officers subject people to profound bodily and psychological horror, it is something else, something other than torture.

This book is thus as much about wilful ignorance and national self-delusion as it is about the physical mechanics of torture.

Despite vigorous debates amongst contemporaries, and copious historical evidence to the contrary, Americans have repeatedly pleaded ignorance about the actions of the state. Brundage’s book is a welcome corrective, posing a profound and systematic challenge to this ‘compulsion to restore national innocence’.

7 November 2003. Corporal Charles Graner and Specialist Sabrina Harman pose for a picture behind nude detainees at Abu Ghraib (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Brundage also demonstrates that US officials and the broader public have frequently accepted torturous practices, as long as they occur in a state of exception and to those viewed as outsiders.

Whether that be the War on Terror, the War on Drugs, the War on Crime, or the Civil War, critics of state violence are told that the pain and suffering of a minority is necessary to preserve the security of the majority.

Victims of torture (whether they be slaves, Native Americans, criminals, prisoners, or ‘illegal enemy combatants’) are rhetorically defined as barbarous and uncivilised adversaries, unworthy of the protections officially offered by the state.

Although each case study includes voices that spoke in horror at what was done in the name of America, in most instances these critics had little success in halting abhorrent practices or in holding individual torturers (let alone those in power) to account.

Understanding the history of torture in the United States will not prevent future violence, but Brundage views this information as providing an important framework for an engaged citizenry.

Civilizing Torture encourages the reader to look carefully at the ‘subtle work of denial and erasure’ used by torture apologists, to be aware of the circumstances that are used to justify torture, and to be conscious of the types of people likely to experience the unchecked violence of the state.

Given that the current occupant of the White House has insisted that torture ‘absolutely’ works and has boasted he ‘would bring back a hell of a lot worse than waterboarding’, the lessons of Civilizing Torture feel positively urgent.

Prudence Flowers is a lecturer in the history program at Flinders University. She teaches and writes about the United States, with a particular focus on social movement activism, conservative group formation and ideology, and the politics of gender and sexuality. She is the author of The Right-to-Life Movement, the Reagan Administration, and the Politics of Abortion (Palgrave, 2019). For more information, see her staff webpage:https://www.flinders.edu.au/people/prudence.flowers

This article was originally published by “ABR“

The 21st Century