What’s a riot without looting? We want it, they’ve got it! You’d think from the press that looting was alien to British tradition, imported by immigrants more recent than the Normans. Not so. Gavin Mortimer, author of The Blitz, had an amusing piece in the First Post about the conduct of Britons at the time of their Finest Hour:

“It didn’t take long for a hardcore of opportunists to realise there were rich pickings available in the immediate aftermath of a raid – and the looting wasn’t limited to civilians.

“In October 1940 Winston Churchill ordered the arrest and conviction of six London firemen caught looting from a burned-out shop to be hushed up by Herbert Morrison, his Home Secretary. The Prime Minister feared that if the story was made public it would further dishearten Londoners struggling to cope with the daily bombardments…

“The looting was often carried out by gangs of children organized by a Fagin figure; he would send them into bombed-out houses the morning after a raid with orders to target coins from gas meters and display cases containing First World War medals.

In April 1941 Lambeth juvenile court dealt with 42 children in one day, from teenage girls caught stripping clothes from dead bodies to a seven-year-old boy who had stolen five shillings from the gas meter of a damaged house. In total, juvenile crime accounted for 48 per cent of all arrests in the nine months between September 1940 and May 1941 and there were 4,584 cases of looting.

“Joan Veazey, whose husband was a vicar in Kennington, south London, wrote in her diary after one raid in 1940: “The most sickening thing was to see people like vultures, picking up things and taking them away. I didn’t like to feel that English people would do this, but they did.”

“Perhaps the most shameful episode of the whole Blitz occurred on the evening of March 8 1941 when the Cafe de Paris in Piccadilly was hit by a German bomb. The cafe was one of the most glamorous night spots in London, the venue for off-duty officers to bring their wives and girlfriends, and within minutes of its destruction the looters moved in.

“Some of the looters in the Cafe de Paris cut off the people’s fingers to get the rings,” recalled Ballard Berkeley, a policeman during the Blitz who later found fame as the ‘Major’ in Fawlty Towers. Even the wounded in the Cafe de Paris were robbed of their jewellery amid the confusion and carnage.”

A revolution is not a tea party, sniffed Lenin, but he should have added that it often starts off with a big party. Perhaps he was acknowledging that when he said a revolution was “a festival of the oppressed.” After the storming of the Winter Palace in October 1917 everyone was drunk for three days, conduct of which the prissy Vladimir Illich no doubt heartily disapproved.

The riots in London in August 2011 started in Tottenham in an area with the highest unemployment in London, in response to the police shooting a young black man, in a country where black people are 26 times more likely to stopped and searched by the cops than whites. Stop-and-searches are allowed under Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, introduced to deal with football hooligans.

It allows police to search anyone in a designated area without specific grounds for suspicion. Use of Section 60 has risen more than 300 per cent between 2005 and last year. In 1997/98 there were 7,970 stop-and-searches, increasing to 53,250 in 2007/08 and 149,955 in 2008/09. Between 2005/06 and 2008/09 the number of Section 60 searches of black people rose by more than 650 per cent.

The day after the heaviest night of rioting we saw Darcus Howe, originally from Trinidad and former editor of Race and Class, now a broadcaster and columnist, being questioned by a snotty BBC interviewer, Fiona Armstrong. We ran it last week as website of the day.

Howe linked the riots to upsurges by the oppressed across the Middle East and then remarked that when KillingTrayvons1he’d recently asked his son how many times he’d been stopped and searched by the police, his boy answered that it had happened too often for him to count.

To which point Ms Armstrong, plainly irked by the trend in the conversation in which Howe was conspicuously failing in his assigned task – namely to denounce the rioters – said nastily, ““You are not a stranger to riots yourself I understand, are you? You have taken part in them yourself?”

“I have never taken part in a single riot. I’ve been on demonstrations that ended up in a conflict,” the 67-year old Howe answered indignantly. “Have some respect for an old West Indian negro and stop accusing me of being a rioter because you wanted for me to get abusive. You just sound idiotic — have some respect.” The BBC later apologized to those offended by what it agreed was “a poorly phrased question.”

Back in 1981, Cockburn interviewed Howe in his Race and Class office after the Brixton and Toxteth riots. Overweening police power and state racism were fuelling unofficial racism, with innumerable murderous attacks on blacks in a Britain ravaged by Margaret Thatcher’s economic policies. At the start of April, 1981, the police launched Operation Swamp 81 to combat street crime.

More than 1,000 people were stopped and questioned in the first four days. The uprising in Brixton began on April 9 and lasted through April 11. There were 4,000 police in the area and 286 people arrested. By the weekend of July 10-12 riots were taking place in 30 towns and cities – black and white youths together and in some case white youths alone. They were scenes, as Lord Scarman said of Brixton, “of violence and disorder… the like of which had not previously been seen in this century in Britain.

“The riots opened up an entirely new political ethos,” Howe said back then. “To understand the organizational stages that we are moving to, it is essential to know that in the late 1960s there were black-power organizations in almost every city in this country. A combination of repression – not as sharp as in the United States – but repression British style and Harold Wilson’s political cynicism undermined that movement.

What he did was offer a lot of money to the black community, which set up all kinds of advice centers and projects for this and projects for that. So, in some black communities, if you have a headache somebody is onto you saying, ‘Well, look, I have a project with blacks with headaches.’

That paralysed the political initiative of blacks. It was done for you by the state and, as you know, Britain is saturated with the concept of welfare.The riots have broken through that completely, smashed it to smithereens, indicating that it has no palliative, no cure for the cancer.”

AC: “You’re looking toward a black/white mass organization?”

“Black/white mass movement. But one must always point to what we are heading for. What are we aiming for? Are we aiming for the vulgarity of a better standard of living. I think a passion has arisen in the breasts of millions of people in the world for a kind of democratic form and shape which would equal parliamentary democracy in its creativity and innovation.”

AC: “Let’s look at a likely future for Britain: enormous structural unemployment, the creation of a permanent underclass..”

“Permanent unemployed, that is what is on the agenda, with the revolutionizing of production, with the microchip. Now what the British working class has to do is break out of this demand for jobs, which characterized the 1930s, the Jarrow marches, and so on. They will have to lift themselves to the new reality, which will of course call for the merciless shortening of the working day, the working week, and the working life, and a concentration on leisure and the quality of work… They say, ‘March for jobs.’ What jobs?”

AC: It’s stimulating to hear you say this, because the left seems to have a lot of illusions about this. The slogan should really be, ‘Less work,’ not ‘More work.’

“’Less work, more money.’ And that’s a vulgarity too. ‘Less work, more leisure.’ We have built up over the centuries the technological capacity to release people from that kind of servitude.”

AC: So then you have to talk about redistribution of wealth.

“Free distribution. A completely new ethos. And we are on the verge of it. “

AC: Don’t you think that pathological symptoms, including racism, will increase as people fight on the scrap heap, as the economy goes down?”

“I agree. Something else increases too. Side by side, living in the same atom as pathology, is the possibility to lift. You can’t reach the lifting stage without the pathological stage. Crabs in a barrel. Or you leap. The leap depends on what dominant political ideology is presented to the population.”

AC: You view the current decline of the Labour Party with considerable optimism?”

“Considerable optimism.”

It was six in the evening and outside the Race and Class offices people were sloshing through the puddles on the way home from work, or standing about in doorways. Howe got up and stretched, then picked up a document.

“Listen to this,” he said. “After the uprising in Moss Side last July they appointed a local Manchester barrister called Hytner to enquire into what happened. Here’s what he writes:

“At about 10.20 pm a responsible and in our view reliable mature black citizen was in Moss Side East and observed a large number of black youths whom he recognized as having come from a club a mile away. At the same time a horde of white youths came up the road from the direction of Moss Side. He spoke to them and ascertained they were from Wythenshawe. The two groups met and joined. There was nothing in the manner of their meeting which in any way reflected a prearranged plan. There was a sudden shout and the mob stormed off in the direction of Moss Side police station. We are given an account by another witness who saw the mob approach the station, led, so it was claimed, by a nine-year-old boy with those with Liverpool accents in the van.’”

Howe smiled. “Whites from Wytheshawe, blacks from Moss Side, no prearranged plan. They gather. There was a shout. ‘On to Moss side police station.’ That gives you some indication. You must have a convergence of interests in order for that to happen.”

That was a interchange at the start of the Eighties. Here we are thirty years later, structural unemployment etched ever more deeply into the economy of Britain, now in a melding of Thatcherism and New Labor’s follow-on from Thatcherism, abysmal poverty and hopelessness in Tottenham and similar districts coexisting at close quarters with profligacy and corruption saturating the higher social tiers and the political sector in one of the most unequal, class-divided cities in Europe.

As the Daily Mash puts it:

“Many of these kids are less then two miles away from people who get multi-million pound bonuses for catastrophic failure and live in a culture where the material excess of people who are famous for nothing is rammed relentlessly into their faces by middle-brow tabloid newspapers. And of course later today the looters will be condemned in Parliament by a bunch of people who stole money by accident.”

Bands of youths make for stores in Central London in part to exact revenge on places that contemptuously rejected their applications for a job. One group methodically worked its way through a tony restaurant in Notting Hill Gate, relieving the clientele of their wallets.

It’s difficult to assess what levels of political organization there are in the ghettos, nor the possibility of unity, amid the stories of murderous racial clashes between blacks and Asians, with Turks and Sikhs arrayed in defense of their modest stores and temples.

On the state agenda of every advanced industrial nation, in the ebb from the great post World War 2 economic boom, is the simple question: amid vast structural unemployment and diminished social expectations how best to assuage the alarm expressed by James Anderton in 1980, when he was Chief Constable of Greater Manchester. Anderton gave it as his considered opinion that “from the police point of view … theft, burglary, even violent crime will not be the predominant police feature. What will be the matter of greatest concern will be the covert and ultimately overt attempts to overthrow democracy, to subvert the authority of the state.”

Britain had its Notting Hill Gate riots in 1958, and Justice Salmon sent nine white Teddy Boys to long terms in prison, saying, “We must establish the rights of everyone, irrespective of the color of their skin … to walk through our streets with their heads erect and free from fear.”

Twenty years later, in 1978 Judge McKinnon ruled that Kingsley Read, head of the fascist National Party, was not guilty of incitement to racial hatred when he said publicly of 18-year-old Gurdip Singh Chaggar, set upon by white youths and stabbed to death, “One down, one million to go.”

In the interval British governments, both Conservative and Labour, falteringly, with occasional remissions and bouts of bad conscience, proceeded down the path to racism. Pace David Cameron’s recent pronouncement of its death, between the late 1940s and the late 1960s the chance of establishing a multiracial society was squandered.

In the 1960s, America saw fearsome ghetto riots from Newark, to Detroit, to the city of Watts in Los Angeles. The state’s response was a threefold strategy: first, buy your way out. Money sluiced into “urban renewal schemes” basically aimed as various forms of ethnic cleansing and wholesale destruction of black neighborhoods. Gentrification and deindustrialization assisted in this process. Across the next twenty years, for example, the manufacturing base of Los Angeles simply disappeared.

Since these shifts involved the creation of new ghettos, the second strategy was ever more stringent policing, with federal money pouring into city law enforcement across the country, the creation of heavily armed SWAT teams, even in tiny communities.

The third strategy was the conversion of a political threat – political activism by the Black Panthers and other national organizations (many of whose leaders were straightforwardly murdered by the police) – into a crime problem, a.k.a the “war on drugs,” launched in 1969 by Richard Nixon who emphasized to his chief aide, H.R. Haldeman, that the whole problem [drugs] was really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to.”

There is plenty of evidence that the strategists of the state’s response to black political insurgency were far from unhappy to see poor neighborhoods demobilized by drugs, black-on-black violence, as gangs fought bloody turf wars for street corner concessions.

Across the next 35 years the U.S. prison population rose relentlessly, the cells disproportionately filled with blacks and Hispanics. The “system” had devised a useful differential in sentencing that saw blacks and other poor people serving vastly longer terms for possession of crack, rather than powder cocaine – a middle-class preference.

The last major race riot in America was in 1992, following the release of a video of a black man, Rodney King, being savagely beaten by Los Angeles cops. By the 1990s, the “buy-out” strategy had evolved into vast programs of prison construction, paralleling the rise of gated residential communities replete with walls and armed guards keeping the bad guts out.

America has been slowly waking up to two increasingly self-evident truths: violent crime rates – for murder, robbery, aggravated assault and rape – have been falling, and are now at their lowest level for nearly 40 years. Fears that the 2008 crash and indisputably harsh economic times for poor people would produce a new crime wave have proved to be baseless. In 2010, New York saw 536 murders – 65 more than in 2009, which was the lowest since 1963.

All crime rates in Los Angeles have been dropping for two decades. Homicides plunged 18 percent last year. Violent crime is roughly the same in LA as in Portland, Oregon, the whitest major city in America, the same as it was in the lily-white LA of the early 1960s. The 1960s, when crime rates rose, had roughly the same unemployment rate as the late 1990s and early 2000s, when crime fell.

Twenty years ago, conservative criminologists here were drawing up graphic scenarios of cities held hostage by gangs of feral black youth. City police forces compiled vast computer data banks of “gangs,” and suspects linked to a gang drew heavier sentences, shoved into a penal system where remedial counseling, post release job training had vanished.

Did crime fall because all the bad guys were locked up? No one claims this beyond 25 percent of the reduction – itself a very high estimate. Another theory is that by the mid 1990s the crack wars were over, and the victors enjoying their hard-won monopolies under the overall supervision of the police. Other theories were recently explored by professor James Q. Wilson, an influential conservative sociologist:

“There may also be a medical reason for the decline in crime. For decades, doctors have known that children with lots of lead in their blood are much more likely to be aggressive, violent and delinquent. In 1974, the Environmental Protection Agency required oil companies to stop putting lead in gasoline. At the same time, lead in paint was banned for any new home (though old buildings still have lead paint, which children can absorb). Tests have shown that the amount of lead in Americans’ blood fell by four-fifths between 1975 and 1991. A 2007 study by the economist Jessica Wolpaw Reyes contended that the reduction in gasoline lead produced more than half of the decline in violent crime during the 1990s in the U.S. and might bring about greater declines in the future.”

Cocaine use has been declining. Wilson cites a study of 13,000 people arrested in Manhattan between 1987 and 1997, a disproportionate number of whom were black: “Those born between 1948 and 1969 were heavily involved with crack cocaine, but those born after 1969 used very little crack and instead smoked marijuana.

The reason was simple: the younger African Americans had known many people who used crack and other hard drugs and wound up in prisons, hospitals and morgues. The risks of using marijuana were far less serious. This shift in drug use, if the New York City experience is borne out in other locations, can help to explain the fall in black inner-city crime rates after the early 1990s.”

Simultaneous with the drop in violent crime rates has come the discovery that America can’t afford to lock up 2.3 million people for years on end. It’s too expensive. When he’s not praying to a Christian God to save America, Gov. Rick Perry of Texas is trying to save the state’s budget in part by getting convicts out of prisons and into various diversion programs.

So, by after a nearly 40-year detour into a gulag Republic, with 25 percent of the world’s prisoners, America is retrenching toward softer solutions. The War on Drugs and the War and Crime carry a heavy price tag. A generation’s worth of “wars on crime” and of glor ification of the men and women in blue have engendered a culture of law enforcement that is all too often vicious ly violent, contemptuous of the law, morally corrupt, and confident of the credulity of the courts.

In Chicago, police ignored witnesses, dis counted testimony, as they bustled the innocent onto Death Row. In New York, a plain-clothes posse of heavily armed cops roamed the streets, justifiably confident that their lethal onslaught would receive official protec tion, which it did until an unprecedented popular uproar brought the perpetrators to book.

These aren’t isolated cases. There isn’t a state in the union where cops aren’t perjuring themselves, using excessive force, targeting minorities.

Those endless wars on crime and drugs – a staple of 90 percent of America’s politicians these last thirty years – have engendered not merely 2.3 million prisoners but a vindictive hysteria that pulses on the threshold of homi cide in the bosoms of many of our uniformed law enforcers. Time and again, one hears stories attesting to the fact that they are ready, at a moment’s notice or a slender pretext, to blow someone away, beat him to a pulp, throw him in the slammer, sew him up with police perjuries and snitch-driven charges, and try to toss him in a dungeon for a quarter-century or more.

The price for decades of this mythmaking and cop boosterism? It was summed up in the absurdity of the declaration of the U.S. Supreme Court, in 2000, that flight from a police officer constitutes sound reason for arrest. Actually, it constitutes plain common sense.

Emergency laws, rushed through by panicked politicians, are always bad. It will take America many decades, if ever, to restore civil liberties, approach crime rationally – and this will only come with courageous and inventive political leadership in the poor communities. Britons should study carefully the lessons of Americans’ 40-year swerve.

Back in 1981 Howe put the right questions on the agenda. We’ve got further away from answering them, and in fact the left rarely asks them at all, bobbing along in the neoliberal backwash that began in the early 1970s.

Alexander Cockburn’s Guillotined! and A Colossal Wreck are available from CounterPunch.

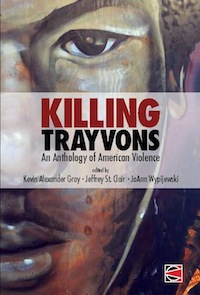

Jeffrey St. Clair is editor of CounterPunch. His new book Killing Trayvons: an Anthology of American Violence (with JoAnn Wypijewski and Kevin Alexander Gray) will be published this summer by CounterPunch Books. He can be reached at: sitka@comcast.net.

This article originally appeared in the August 2011 edition of CounterPunch.