An unstoppable tide of radioactive trash and chemical waste from Fukushima is pushing ever closer to North America.

An estimated 20 million tons of smashed timber, capsized boats and industrial wreckage is more than halfway across the ocean, based on sightings off Midway by a Russian ship’s crew. Safe disposal of the solid waste will be monumental task, but the greater threat lies in the invisible chemical stew mixed with sea water.

This new triple disaster floating from northeast Japan is an unprecedented nuclear, biological and chemical (NBC) contamination event. Radioactive isotopes cesium and strontium are by now in the marine food chain, moving up the bio-ladder from plankton to invertebrates like squid and then into fish like salmon and halibut.

Sea animals are also exposed to the millions of tons of biological waste from pig farms and untreated sludge from tsunami-engulfed coast of Japan, transporting pathogens including the avian influenza virus, which is known to infect fish and turtles.

The chemical contamination, either liquid or leached out of plastic and painted metal, will likely have the most immediate effects of harming human health and exterminating marine animals.

The toxic mess won’t stop at the shoreline. Many chemical compounds are volatile and can evaporate with water to form clouds, which will eventually precipitate as rainfall across Canada and the northern United States. The long-term threat extends far inland to the Rockies and beyond, affecting agriculture, rivers, reservoirs and, eventually, aquifers and well water.

Falsifying Oceanography

Soon after the Fukushima disaster, a spokesman for the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) at its annual meeting in Vienna said that most of the radioactive water released from the devastated Fukushima No.1 nuclear plant was expected to disperse harmlessly in the Pacific Ocean.

Another expert in a BBC interview also suggested that nuclear sea-dumping is nothing to worry about because the “Pacific extension” of the Kuroshio Current would deposit the radiation into the middle of the ocean, where the heavy isotopes would sink into Davy Jones’s Locker.

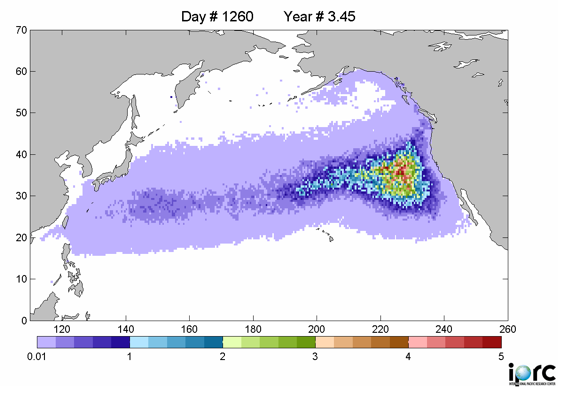

At the time, this writer challenged this sort of unscientific hogwash since oceanographic studies have long indicated the Kuroshio (Black Stream) is the driving force for the North Pacific Current, which rapidly traverses the ocean to North America. The current is a relatively narrow band that acts like a conveyer belt, meaning radioactive materials will not disperse and settle but should remain concentrated

Soon thereafter, the IAEA backtracked, revising its earlier implausible scenario. In a newsletter, the atomic agency projected that cesium-137 might reach the shores of other countries in “several years or months.” To be accurate, the text should have been written “in several months rather than years.”

The Great Gyre

The network of currents comprise a larger hydrodynamic system known as North Pacific Gyre. Flotsam and jetsam from northeast Japan are moved along this path:

– The Liman or Oyashio (Parent Stream), a mineral-rich cold Arctic current that moves southwest from the Bering Strait past Kamchatka Peninsula and along Japan’s northeast region of Tohoku. The water used to cool the Fukushima meltdown is dumped into the passing Liman, which carries the radioactive wastewater southward toward Choshi Point, east of Tokyo..

– The rocky outcrop at Choshi forces the Liman to swerve eastward, where it collides with the tropical Kuroshio Current moving northward. The interaction of these opposing currents is complicated. The cold Liman is forced underneath the warm Black Tide, which explains why rockfish, abalone, sea urchins and other bottom dwellers have high readings of radioactivity.

An analysis lab in Fukushima has reported 15,000 becquerels per kg, or six times the legally allowable content. (The studies, like all in Japan, use the controversial method of taking average readings from entire samples, instead of measuring hot spots that can be 5 times higher.)

– Along the boundaries of the two currents, gigantic eddies are spun off. The mixing of nutrient-rich cold water with the warm current spurs the genesis of marine life, spawning algae and the larvae of fish and invertebrates. The waters off eastern Japan form the world’s richest fishery.

Of special importance in the food chain are squid, cuttlefish and others in the cephalopod family, which comprise the basic source of protein for fish.

– The merged Liman and Kuroshio become the North Pacific Current, pushing eastward to North America. Large predatory species, including tuna and salmon, feed here on the contaminated squid and on small fishes like herring and mackerel.

– When the North Pacific Current hits the continental shelf, it divides. One stream veers northward along the Canadian and Alaskan coast, and then swings counterclockwise toward the Bering Strait and Kamchatka Peninsula. These areas are the breeding grounds of seals, walruses, whales and sea otters. The region is also a major supplier of salmon and sea cucumbers for the Asian markets.

– The other stream turns clockwise to the south, becoming the California Current, the breeding waters of sea lions, pelicans and humpback whales. That southern stream eventually splits into two new currents: the Equatorial Pacific, which moves from Mexico to the Philippines, where it rejoins the Kuroshio; and the Peruvian, heading southward along the coast of South America and then westward into the South Pacific.

Mega-scale fluid dynamics show that the Fukushima nuclear disaster will soon contaminate most of the vital fisheries of the Pacific, which comprises half of the world’s sea surface.

Over the 30-year half-life of cesium, radioactive isotopes will be recycled a dozen times or more. Once into the Southern Sea surrounding Antarctica, the radioactive substances will move into the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

If some evil genius, a modern-day Captain Nemo, were to plan the extermination of life on Earth, there could hardly be a better spot for hatching this nefarious plot than Fukushima.

D-Day Won’t Wait

When will the radioactive waste arrive on the West Coast? The distance between northeast Japan and the Pacific Northwest is about 8,000 kilometers. The Kuroshio-North Pacific Current normally makes the passage in about six to seven months.

Heavier materials, such as timber, will move at about half that pace, but chemicals dissolved in the water have already started to reach the Pacific seaboard of North America, a reality being ignored by the U.S. and Canadian governments.

It is all-too easy for governments to downplay the threat. Radiation levels are difficult to detect in water, with readings often measuring 1/20th of the actual content.

Dilution is a major challenge, given the vast volume of sea water. Yet the fact remains that radioactive isotopes, including cesium, strontium, cobalt and plutonium, are present in sea water on a scale at least five times greater than the fallout over land in Japan.

According to a recent estimate by the France-based Institute for Radiological Protection and Nuclear Safety, radioactive sea-dumping from Fukushima is 30 times the amount stated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company. The total amount leaked into the sea is closer to 27 quadrillion becquerels.

A quadrillion is 1,000 trillion. That does not include airborne isotopes that have fallen into the Pacific. Unlike those stories about arsenic, a tiny dose every day of cesium will not make one immune from its toxic effect.

Chemical Dependency

Japan along with many other industrial powers is addicted not just to nuclear power but also to the products from the chemical industry and petroleum producers.

Based on the work of the toxicologist in our consulting group who worked on nano-treatment system to destroy organic compounds in sewage (for the Hong Kong government), it is possible to outline the major types of hazardous chemicals released into sea water by the tsunami.

– Polychlorinated biphenols (PCBs), from destroyed electric-power transformers. PCBs are hormone disrupters that wreck reproductive organs, nerves and endocrine and immune system.

– Ethylene glycol, used as a coolant for freezer units in coastal seafood packing plans and as antifreeze in cars, causes damage to kidneys and other internal organs.

– The 9-11 carbon compounds in the water soluble fraction of gasoline and diesel cause cancers.

– Surfactants, including detergents, soap and laundry powder, are basic (versus to acidic) compounds that cause lesions on eyes, skin and intestines of fish and marine mammals.

– Pesticides from coastal farms, organophosphates that damage nerve cells and brain tissue.

– Drugs, from pharmacies and clinics swept out to sea, which in tiny amounts can trigger major side-effects.

Start of a Kill-Off

Radiation and chemical-affected sea creatures are showing up along the West Coast of North America, judging from reports of unusual injuries and mortality.

– Hundreds of large squid washed up dead on the Southern California coast in August (squid move much faster than the current).

– Pelicans are being punctured by attacking sea lions, apparently in competition for scarce fish.

– Orcas, killer whales, have been dying upstream in Alaskan rivers, where they normally would never seek shelter.

— Ringed seals, the main food source for polar bears in northern Alaska, are suffering lesions on their flippers and in their mouths. Since the Arctic seas are outside the flow from the North Pacific Current, these small mammals could be suffering from airborne nuclear fallout carried by the jet stream.

These initial reports indicate a decline in invertebrates, which are the feed stock of higher bony species. Squid, and perhaps eels, that form much of the ocean’s biomass are dying off. The decline in squid population is causing malnutrition and infighting among higher species.

Sea mammals, birds and larger fish are not directly dying from radiation poisoning it is too early for fatal cancers to development. They are dying from malnutrition and starvation because their more vulnerable prey are succumbing to the toxic mix of radiation and chemicals.

The vulnerability of invertebrates to radiation is being confirmed in waters immediately south of Fukushima. Japanese diving teams have reported a 90 percent decline in local abalone colonies and sea urchins or uni. The Mainichi newspaper speculated the losses were due to the tsunami.

Based on my youthful experience at body surfing and foraging in the region, I dispute that conjecture. These invertebrates can withstand the coast’s powerful rip-tide.

The only thing that dislodges them besides a crowbar is a small crab-like crustacean that catches them off-guard and quickly pries them off the rocks. Suction can’t pull these hardy gastropods off the rocks.

Tsunami action seems even unlikelier based on my discovery of hundreds of leather-backed sea slugs washed ashore near Choshi.

These unsightly bottom dwellers were not dragged out to sea but drifted down with the Liman current from Fukushima. Most were still barely alive and could eject water although with weak force, unlike a healthy sea squirt.

In contrast to most other invertebrates, the Tunicate group possesses enclosed circulatory systems, which gives them stronger resistance to radiation poisoning. Unlike the more vulnerable abalone, the sea slugs were going through slow death.

Taking Action:

Official denial and downplaying of the true extent of the Fukushima crisis prevented any effective responses that could have contained the toxic spillage into the Pacific.

Instead of containment, the Japanese government promoted sea-dumping of nuclear and chemical waste from the TEPCO Fukushima No.1 plant. The subsequent “decontamination” campaign using soapy water jets is transporting even more land-based toxins to the sea.

What can Americans and Canadians do to minimize the waste coming ashore? Since the federal governments in the U.S. (home of GE) and Canada (site of the Japanese-owned Cigar Lake uranium mine) have decided to do absolutely nothing, it is up to local communities to protect the coast.

First, it is much easier to tow solid waste by boat while it is still at sea than to manhandle the trash along the shore. Methods to net or grapple the beams and solid trash need to be worked out.

Second, rocky islets need to be identified as temporary holding centers for the flotsam.

Third, oil-spill booms can be installed around harbors and key coves in nature reserves to hold back solid waste and lighter liquid chemicals. Pressure from estuaries and brackish lagoon water can have a buffering effect to keep the most toxic waste at bay.

Fourth, self-enclosed incinerators with bio-filters need to be built to reduce the volume of solid waste to ash destined for a hazardous-waste landfill.

Fifth, the health monitoring system for fish needs to be expanded to cover a wider range of toxins including radioactive isotopes, with regular reporting to the public.

Sixth, contingency plans need to be devised in event of a kill-off of marine mammal populations or, worse, any massive impact on human health, for example in case of related contamination of rainwater. Policy must focus on species survival along with economic revival.

By Yoichi Shimatsu, Hong Kong-Based Environmental Consultant

Former General Editor Japan Times Weekly In Tokyo

http://rense.com/general95/death.htm

Exclusive To Rense.com