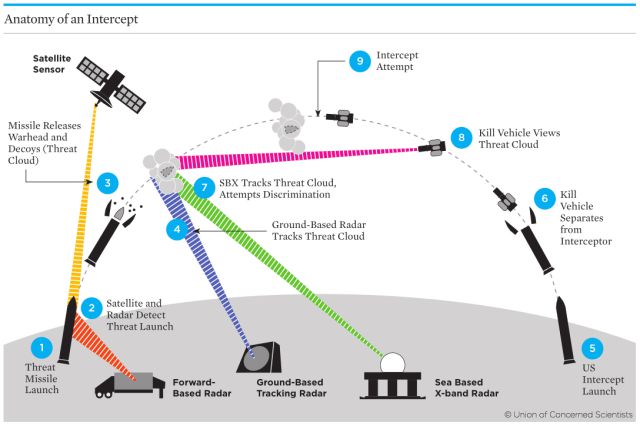

How the missile defense system works. (Union of Concerned Scientists)

At a Nov. 6 press conference with US President Donald Trump, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was asked if Japan would respond to North Korean missile launches by shooting them down.

“I could just take a piece of the Prime Minister’s answer,” Trump interjected, “He will shoot them out of the sky when he completes the purchase of lots of additional military equipment from the United States. He will easily shoot them out of the sky, just like we shot something out of the sky the other day in Saudi Arabia.”

But Trump was wrong: The US can’t easily shoot down missiles like the one North Korea tested yesterday, which are designed to launch nuclear weapons. The Saudi military did intercept a missile using a US-made Patriot missile defense system, but it was a medium-range missile moving at far slower speeds than a nuclear warhead launched by an inter-continental ballistic missile.

Stopping a nuclear ICBM is a much more difficult challenge, one that the US has struggled with since the Cold War, spending hundreds of billions of dollars to come up with a system of sensors and missiles called GMD, or Ground-based Midcourse Defense.

The premise is simple: Once the US detects a missile launch with a variety of radar systems, it will shoot its own interceptor into the sky. After the enemy nuclear warhead separates from its rocket booster, a defensive interceptor, or “kill vehicle,” separates from its own booster and attempts to crash into the warhead. Executing this maneuver during a roughly twenty minute window against a warhead moving faster than the speed of sound is extremely difficult in practice.

“The US missile interceptors based in Alaska and California are assessed to have a 25 percent chance of a head-on collision with the attacking missile, but most experts believe the true performance to be much lower,” Dr. Bruce Blair, a former nuclear launch control officer turned anti-proliferation activist, said in a statement.

“It is not a reliable defense under real-world conditions,” echoed experts at the Union of Concerned Scientists in an extensive report published last year. “By promoting [missile interception] as a solution to nuclear conflict, US officials complicate diplomatic efforts abroad, and perpetuate a false sense of security that could harm the US public.”

Even the military’s self-assessments aren’t convincing. The DOD noted in 2016 (pdf) that “the reliability and availability of the operational [ground based interceptors] are low, and the [Missile Defense Agency] continues to discover new failure modes during testing.”

The system has been tested ten times since 2004, succeeding just five times. In one case, the Los Angeles Times caught the Missile Defense Agency promoting a “successful” test despite the fact that the interceptor malfunctioned and would not have stopped a nuclear attack.

There was a successful missile defense test earlier this year—the first attempt to intercept a target in three years, which some analysts say was an improvement. But it didn’t satisfy critics. During the scripted daytime tests, teams operating the interceptors were aware of what kind of vehicle they were shooting at and roughly where it was coming from and going to.

Furthermore, tests don’t address the full range of counter-measures that experts expect enemy ICBMs will use to confuse and divert approaching kill vehicles. The best hope is that launching multiple interceptors at a single warhead will improve the odds.

Some say the answer is throwing more money at the problem, noting that funding for missile defense has been spotty in recent years. Expensive wars against low-tech insurgencies in the Middle East have put investments in anti-nuclear missile technology lower on the priority list.

But government auditors suggest that money spent on missile defense systems isn’t being used all that well to begin with, noting that there is little transparency into what testing will cost or why. US lawmakers just earmarked $4 billion to find other ways to back-stop the system, using drones and fighter jets to go after the nuclear ICBMs earlier in their flight path.

As worrisome as America’s lack of an effective missile defense is, the more pressing concern is whether Trump’s trust in a flawed system is leading him to act belligerently when confronting North Korea. In October, the US president claimed the missile defense system was effective 97% of the time. As one expert put it, “the confidence with which [Trump] made the statement indicates a lack of understanding of the complexities or perhaps a lack of interest in those complexities.”

By Tim Fernholz, Quartz

This article was originally published by Quartz

The 21st Century