In 2019, agents of the federal and state governments persuaded judges to issue 99% of all requested intercepts.

An intercept is any type of government surveillance — telephone, text message, email, even in-person.

These are intercepts that theoretically are based on probable cause of crime, as is required by the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution.

The 2019 numbers — which the government released as we were all watching the end of the presidential election campaign — are staggering.

The feds, and local and state police in America engaged in 27,431,687 intercepts on 777,840 people.

They arrested 17,101 people from among those intercepted and obtained convictions on the basis of evidence obtained via the intercepts on 5,304.

That is a conviction rate of 4% of all people spied upon by law enforcement in the United States.

Here is the backstory.

Readers of this column are familiar with the use by federal agents of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act to obtain intercepts using a standard of proof considerably lesser than probable cause of crime.

That came about because Congress basically has no respect for the Constitution and authorized the FISA Court to issue intercept warrants if federal agents can identify an American or a foreign person in America who has spoken to a foreign person in another country.

Call your cousin in Florence or a bookseller in Edinburgh or an art dealer in Brussels, and under FISA, the feds can get a warrant from the FISA Court to monitor your future calls and texts and emails.

This FISA system is profoundly unconstitutional; the Fourth Amendment expressly requires that the government — state and federal — can only lawfully engage in searches and seizures pursuant to warrants issued by a judge based upon a showing under oath of probable cause of crime.

The Supreme Court has ruled consistently that intercepts and surveillances constitute searches and seizures. The government searches a database of emails, texts or recorded phone calls and seizes the data it wants.

Thus, when the feds have targeted someone for prosecution and lack probable cause of crime about that person, they resort to FISA.

This is not only unlawful and unconstitutional, but also it is corrupting, as it permits criminal investigators to cut constitutional corners by obtaining evidence of crimes outside the scope of the Fourth Amendment.

The use of the Fourth Amendment is the only lawful means of engaging in surveillance sufficient to introduce the fruits of the surveillance at a criminal trial.

If the feds happen upon evidence of a crime from their FISA-authorized intercepts, they then need to engage in deceptive acts of parallel construction.

That connotes the false creation of an ostensibly lawful intercept in order to claim that they obtained lawfully what they already have obtained unlawfully.

Law enforcement personnel then fake the true means they used to acquire evidence — even duping the prosecutors for whom they work — so the evidence will appear to have been obtained lawfully and thus can be used at trial.

At its essence, parallel construction is a deception on the court. If the deception is perpetrated under oath, it is perjury — a felony.

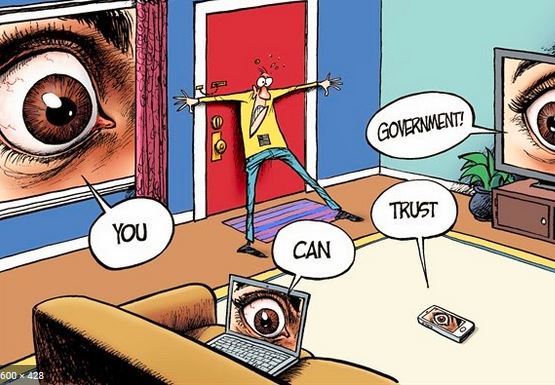

This corruption of the Constitution by those in whose hands we have reposed it for safekeeping happens every day in America.

The FISA-induced corruption has regrettably bled into the culture of non-FISA law enforcement, and even into the judiciary.

The statistics I cited above are not from FISA — those numbers are secret.

Rather, the statistics reflect the government’s voracious appetite for spying that now pervades non-FISA law enforcement.

This is so because judges accept uncritically the applications made before them for intercept or surveillance warrants.

Thus, even though the Fourth Amendment permits judges to issue warrants only upon the probable likelihood of evidence of a crime in the place to be searched or the person or thing to be seized, the attitude of what constitutes probable cause has been attenuated by both the law enforcement personnel who seek warrants and the judges who hear the applications.

We know this because we have not seen a number like 99% of all warrant applications — every one supposedly based on probable cause of crime — granted.

Nor have we seen only 4% of those intercepts resulting in convictions.

The rational conclusion is that the government’s appetite for surveillance remains voracious, and judges — whose affirmative duty it is to uphold the Constitution as against the other two branches of government — have done very little to abate this.

So, what becomes of the remaining 96% of those on whom the government spied? That depends on whether the government charges anyone.

If a person is charged and acquitted, and law enforcement unlawfully obtained evidence against that person, his remedy is either persuading the court to suppress the evidence thus resulting in the acquittal, or suing the law enforcement agents who unlawfully spied on him.

Yet, under current Supreme Court decisions about who can sue the government, if the government has spied on you and not charged you and not told you, you have no cause of action against the law enforcement agents who did this.

Stated differently, in 2019, at least 760,739 people in America were spied upon pursuant to judicial orders allegedly based upon probable cause of crime and were neither charged nor informed of the spying.

My Fox colleagues often deride my attacks on those who fail to safeguard our privacy because they argue, we have no privacy.

Yet, as Justice Louis Brandeis wrote, the most comprehensive of rights is the right to be let alone.

If we forget this, my colleagues will have the last laugh.

If we expose its violation, we might know the joys of unmonitored personal fulfillment.

***

Andrew Peter Napolitano is an American syndicated columnist whose work appears in numerous publications including The Washington Times and Reason. He is an analyst for Fox News, commenting on legal news and trials. Napolitano served as a New Jersey Superior Court judge from 1987 to 1995

Published by Judgenap.com

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.