Yesterday the new SYRIZA-led Greek government, elected on an ‘anti-austerity’ platform, presented its proposals for an alternative debt management regime to an emergency meeting of Eurozone finance ministers in Brussels.

Various options continue to be discussed, including a ‘bridging’ loan to meet short-term cash needs in advance of a comprehensive settlement; swapping some of the debt for ‘growth-bonds’ – a kind of perpetual bond that only pays the holder a dividend when there has been ‘growth’; a partial write-down of a portion of the debt; and a downward revision of the memoranda stipulated primary surplus targets.

The German government continues to stand firm against any re-negotiation of the ‘bailout’ terms initially ‘negotiated’ in 2010. These mandated that, in return for an (eventual) total of €240 billion in loans and a partial write-down of the debt owed to private creditors, the Greek regime implement a drastic regime of de-regulation and privatisation.

The loans were to be payed off by selling off public assets, cutting social expenditure, reducing labour costs and raising fiscal revenues.

The Impact of Austerity

The impact of the austerity regime has been catastrophic. In a paper (1) written in 2013, Maria Markantonatou, an academic at the University of the Aegean in Greece, detailed the impact of the ‘internal devaluation’ that Greece was required to implement in return for the loan package:

- –– Vicious circle of recession.The continuous drop in GDP, in 2011 surpassing the historical maximum for the entire postwar period, led to a rapid reduction in domestic demand. Lower production led to dismissals and the loss of thousands of jobs, further amplifying recession.

- –– Unemployment had already more than doubled within the first three years of austerity and reached 25.4 percent in August 2012. More than half of the population between 15–24 years old is unemployed (57 percent; Eurostat 2012), while thousands of jobs have been lost under conditions of insufficient social protection. Given the continuation of the crisis, the new unemployed become the chronic unemployed.

- –– Rapid labor deterioration, as shown by the increase of precarious and uninsured work, insecurity, degrading payments, weakening of labour rights, and deregulation of labour agreements.

- –– Strangling of the lower middle class, traditionally consisting of small and medium sized enterprises. A great number of such enterprises (family-owned or not) were unable to survive declining consumption, lack of liquidity, and emergency taxes. More than 65,000 of them closed down in 2010 alone, resulting in a “clearance” of such enterprises and disaffecting the people dependent on them.

- –– Migration of younger, highly educated people has risen (“brain drain”), while those studying and living abroad are discouraged to return to Greece, and those who previously would have stayed, are now leaving.

- –– Homelessness increased by 25 percent from 2009 to 2011. Along with the pre-crisis and “hidden” immigrant homelessness, a generation of “neohomeless” now exists who include those with medium or higher educational backgrounds who previously belonged to the social middle.

- –– Suicides hit record levels, increasing by 25 percent from 2009 to 2010 and by an additional 40 percent from 2010 to 2011.

- –– Deterioration of public health evidenced by reduced access to health care services and an increase of 52 percent in HIV infections from 2010 to 2011. Drug prevention centers and psychiatric clinics have closed down due to budget cuts.

To this, one could also add a worrying political impact – that a country with a traditionally weak far right now has one of the largest organised Neo-nazi movements in Europe. In the 2015 legislative elections the ‘Golden Dawn’ secured third place in the popular vote.

‘A Precautionary Tale of the Welfare State?’

But didn’t the Greeks bring this upon themselves? A common view, especially in Northern Europe and the Anglosphere, is that indeed they did. The usual suspects feature in what has become a common neo-liberal narrative – the sordid tale of a welfarist ‘clientelist’ regime with a history of rewarding ‘rent-seeking’ by organised labour, public sector workers and welfare recipients.

Aristides Hatzis, Associate Professor of the Philosophy of Law at the University of Athens, a confirmed neo-liberal and believer in neo-classical economic theory who runs the Greek Crisis blog, expresses the view well when he claims, speaking of the historical causes of the crisis, that ‘Pasok’s economic policies were catastrophic; they created a deadly mix of a bloated and inefficient welfare state with stifling intervention and overregulation of the private sector.’

He goes on to claim that ‘today’s result is the outcome of a disastrous competition between the parties to offer patronage, welfare populism, and predatory statism to their constituencies‘(2).

The title of his article encapsulates this view admirably: Greece as a Precautionary Tale of the Welfare State. A generation of neo-liberal ideology means these sorts of arguments appeal to a wide range of ‘common sense’ views of how economics works. But as is often the case, this kind of ‘common sense’, when exposed to the uncommon facts, turns out to be ideology disguised as insight.

Thanasis Maniatis, Associate Professor in Economics at the University of Athens (3), has shown that Greek Labour – defined as persons who earn or earned their livelihood from the sale of their labour power, whether currently active or retired, together with their dependents – is a net creditor to the Greek state.

In other words, when you factor in all the income and benefit flows and discount all the tax flows, the working class give more to the state than they receive.

In the course of this proof, Maniatis shows that, according to OECD figures for social expenditure as a percentage of GDP, Greece spent 10.3% in 1980, 19.3% in 2000 and 23.5% in 2011. The equivalent figures for Germany are 22.1%, 26.6% and 26.2%. The EU average in in 2011 was 24.9%. When it comes to social spending, far from being bloated, Greece has only just caught up.

The most interesting figures quoted by Maniatis are those from Eurostat comparing averaged values as a percentage of GDP for public expenditure, taxes and deficits between 1995-2012 for the EU-15 and Greece. These show clearly that the major issue in Greece is on the revenue side, not the expenditure side.

The Greek average for government expenditure, at 48.7%, is only 0.6% higher than the EU-15 average. However, the Greek figure for government revenue is 3.6% below the EU-15 average. The Greek budget deficit average is 4.3% higher than the EU-15 average.

So it is quite clear that the Greek budget deficit is driven by a relative shortfall of revenue rather than an excess of expenditure when averaged out over the 1995-2012 period and compared with the fiscal regimes of the other EU-15 nations. Far from being ‘bloated’, she is ‘underfed’.

Maniatis also shows that whereas Greece spent less on education, health and social protection than the EU-15 over the 1995-2012 period, she spent considerably more on interest payments (6.9% compared to 3.5% for the EU-15), general public expenditures – judiciary, police, administration costs etc (12.2% compared to 7% for the EU-15), and defense expenditures (2.9% compared to 1.6% for the EU-15). Where there is ‘bloating’, it is the bankers and the state who benefit.

Why is Greece so poor at collecting taxes? In 2011, Professor Friedrich Schneider of Linz University estimated that in 2010 the Greek black economy was worth 25.5 % of GDP (compared to 10.7% in the UK, 13.9% in Germany, 19.4% in Spain and 21.8% in Italy). The spread in the relative size of the black economy across European countries is commonly linked to variations in levels of self-employment.

In 2013, according to Eurostat, Greece had the highest rates of self-employment in the EU (31.9% compared to an EU average of 15%). Next highest is Italy at 23.4%.

The main structural factor behind varying levels of self-employment in the EU is the size of the agricultural sector and the nature of rural property ownership – in other words, levels of self-employment are related to the size of the agricultural and rural petit-bourgeoisie and modes of rural property ownership.

Far from being the result of some uniquely Greek or welfarist propensity to corruption, the low levels of tax collection in Greece stem from well known structural determinants.

Greece spends twice as much as the EU-15 average on servicing its debt – a debt incurred not to pay for relatively high levels of expenditure, but to cover for relatively low levels of revenue. Finally, the Greek government bureaucracy seems to do very well from expenditure, compared to the EU average, as does the military.

Greece has the highest levels of defense expenditure (as a percentage of GDP) of any NATO member except the notoriously profligate US government. The major overseas benefactor of Greek defense contracts is, of course, the USA.

It seems then that if ‘clientelism’ is a factor in Greek fiscal woes, then the major ‘clients’ are the elements in the professional and agricultural petit-bourgeoisie who don’t pay their taxes, the civil service, the army and the overseas banks – not organised labour, the public sector, the unemployed, the sick and the elderly.

While it is true that the latter have increased their ‘share of the pie’ since 2000, this has been in line with EU trends. Between 1990-2011, social expenditure as a percentage of GDP across the EU-21 rose from 20.6% to 24.9%. In the UK it rose from 16.7% to 23.9%. In France from 25.1% to 32.1%. While in Greece it rose from 16.6% to 23.5%.

Furthermore, the Greeks have worked hard for these gains. According to the OECD, for the period 2000 to 2013, the average Greek worked roughly 500 hours more per year than the average German, and about 400 hours per year more than the average Briton.

Also according to the OECD, the average Greek retirement age is slightly above the average German retirement age. According to the EU (Eurofound), Greeks receive an annual average of 23 vacations days per annum, compared to 30 for Germany.

Has Greece benefited from the Eurozone?

How has the Eurozone impacted Greece? Between 2000-7, Greece, Italy and Spain’s trade deficits with Germany doubled, while Portugal’s quadrupled. Germany’s trade surplus with the rest of the EU tripled in the same period. The Eurozone countries running a trade deficit with Germany no longer have recourse to monetary policy to protect themselves from a more competitive economy.

In addition, Germany benefits as their creditor, recycling surplus Euros as loans to the deficit countries. The recycling of capital from Germany back to her Eurozone export markets was a major driver of the Spanish and Irish property asset bubbles. And it is no coincidence that when the Greek crisis broke in 2010 the majority of privately-owned Greek government debt was held by German banks.

In October 2013, the US Treasury Department’s currency report noted:

“Within the euro area, countries with large and persistent surpluses need to take action to boost domestic demand growth and shrink their surpluses. Germany has maintained a large current account surplus throughout the euro area financial crisis, and in 2012, Germany’s nominal current account surplus was larger than that of China. Germany’s anemic pace of domestic demand growth and dependence on exports have hampered rebalancing at a time when many other euroarea countries have been under severe pressure to curb demand and compress imports in order to promote adjustment. The net result has been a deflationary bias for the euro area, as well as for the world economy. …Stronger domestic demand growth in surplus European economies, particularly in Germany, would help to facilitate a durable rebalancing of imbalances in the euro area”

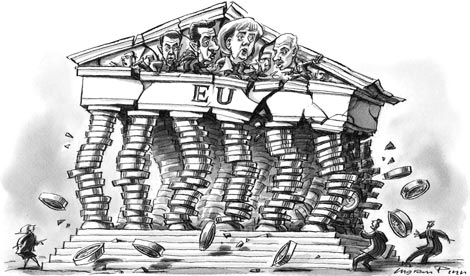

Germany’s commitment to a conservative fiscal policy, low inflation, low wages and export-led growth means that the most powerful economy in the Eurozone, rather than leading the Eurozone out of recession, is leading the Eurozone into debt – mainly to German banks.

There are fundamental structural issues at play here. The German regime seems to be leveraging her economic dominance in the Eurozone to run up significant trade surpluses with the peripheral Eurozone economies. The capital inflows are then recycled back to the debtor economies as loans. A conservative domestic fiscal and inflationary policy preserves Germany’s competitive advantage.

While the Eurozone seems to have been a boon to the German economy, the same cannot be said for Greece.

Austerity is not for all

Is the Greek regime under a moral obligation to repay the debt? Put in more concrete terms – do the primary victims of austerity politics – labour, pensioners, the sick and the poor – ‘owe’ their suffering to the creditors of the Greek government?

Perhaps those among us who are especially prone to bourgeois morality should consider some other recent examples of governments and central banks doling out the cash before becoming overly puritanical about Greek repayments.

For example, between 2008 and 2011, the European Commission approved €4.5 trillion in aid to the financial sector – equivalent to 36.7% of EU GDP (4). Judging by the continued profitability and equity values of many of the banks that benefited from this unparalleled act of emergency public assistance to prop up a failing private sector, the concepts of ‘conditionality’ and ‘austerity’ do not apply when it comes to loans to the financial sector.

Or rather, they do apply – but in this case not to the recipients of the largesse, but to the rest of us who are forced to accept cuts in wages and social benefits as governments seek to claw back some of their loses.

And while Greece has had to borrow its way out of debt, governments are able and willing to exercise a sovereign right to ‘create’ money – as and when they see fit. This is referred to as ‘Quantitative Easing’- essentially, the central bank creates money by fiat and uses it to buy short-term financial instruments – especially bonds – from private banks and investors.

This keeps prices high and yields low, enabling the central bank to keep the cost of borrowing down. It also injects rivers of capital into the financial sector (no austerity required in return).

At the end of 2014 the US Federal Reserve had acquired $4.5 trillion worth of assets as part of its ‘Quantitative Easing’ program. The Bank of England has spend about ₤0.5 trillion on QE. The ECB has just recently announced it is about to begin a cycle of Quantitative Easing.

A Gift for Greece?

The EU/IMF establishment did not implement the Greek bailout as an act of social salvation. In 2010, the US ratings agencies exercised their apparent power to declare nation states bankrupt by rating Greek bonds as ‘junk’ grade. Private capital flows dried up and Greece faced an imminent liquidity crisis. At that stage, the EU/ECB/IMF stepped in.

The proximate cause of the crisis was the revelation that the Greek government had lied for a decade about the true state of fiscal finances.

Government fiscal estimates had consistently over-estimated revenues, and statistical information provided to the EU and to the markets had frequently been criticised as inaccurate and misleading.

In 2010, it was alleged that the Greek regime had payed private investment banks, including Goldman Sachs, hundreds of millions in fees to arrange under-the-radar financial deals that enabled the Greek government to mislead the EU about compliance with EU fiscal governance.

In 2010, when Eurostat revised its statistical profile of the Greek economy, the 2009 fiscal deficit estimate was almost doubled from about 7% to about 16%, and the 2009 debt-to-GDP ratio estimate was revised upwards from 113% to 130%. At that stage, private funding of government debt virtually dried up.

Who benefited from the liquidity released to Greece as part of the Bailout deal? Clearly not the Greek people – least of all the Greek working class. In fact, up to a quarter flowed straight to the private banks that held maturing Greek debt (5). And of course by that stage the Hedge funds had got involved, offloading a lot of the high-risk debt from the commercial banks in between the first and second tranches of loans.

The popular perception is that the troika stepped in to bail out the Greek people. The reality is that the troika advanced the Greek government the liquidity required to cover its debt maturity obligations to the banking sector as well as its cash needs. In return, it forced the Greek regime to begin to claw back the loan (plus interest) from the Greek people via a drastic austerity regime.

SYRIZA…

In the legislative elections of 2015, the people of Greece elected what some are claiming is, on paper, the most radical left-wing government to come to power in Europe since the Spanish and French Popular Fronts of 1936. In the follow up, we will examine what SYRIZA’s options are for dealing with the Greek crisis.

By LJ REYNOLDS, CounterBlast

<a title=”Counterblast” href=”http://counterblastnews.wordpress.com” target=”_blank”>Counterblast</a> is a new blog of news and views featuring original posts by LJ Reynolds.

1 Maria Markantonatou – Diagnosis, Treatment, and Effects of the Crisis in Greece: A “Special Case” or a “Test Case”?, Max Planck Institute Discussion Paper 13/3, February 2013

2 Aristides Hatzis – “Greece as a Precautionary Tale of the Welfare State”, After the Welfare State, Students for Liberty, 2012.

3 Thanasis Maniatis – “The fiscal crisis in Greece: whose fault?”, Greek Capitalism in Crisis, Routledge, 2015.

4 A Cautionary Tale, Oxfam Briefing paper 174, September 2013.