The semi-colonial rule of imperialism over South Korea stopped the national-democratic revolution of the Korean people. It will only conclude with the liberation of South Korea and the reunification of the entire peninsula independently of imperialism, writes Eduardo Vasco.

The theory of permanent revolution and the precedents of the Korean revolution

I

With an ancient civilization, Korea has always been a country that has fought, throughout its history, against the domination of foreign forces. It had to face Mongol, Chinese and Japanese invasions until, in the 19th century, at the height of liberal capitalism that, from the West, imposed its dominance on the East, there was the beginning of the harshest invasion and subsequent submission of the Korean people.

In a similar way to what happened with China in the same period, Korea was a victim of harassment from European, North American and Japanese imperialism who, in order to open the country to imperialist capital, imposed commercial treaties that completely subjugated the sovereignty of the peninsula.

Hence the process of capitalist development that led to the emergence of the Korean proletariat, still small at the beginning of the 20th century but which, faced with internal contradictions, found itself impelled to the revolutionary enterprise in the 1920s.

The Korean Revolution dates back to the second half of the 19th century, with the birth of an embryonic nationalist movement against imperialist domination. However, from 1905 and, finally, from 1910, the Japanese Empire imposed official rule on Korea, completely conquering it as a colony.

This dominance accentuated the contradictions of Korean capitalist development, combined with an extensive agrarian structure and the Asian mode of production, leading to an unprecedented spoliation of the country and enormous exploitation of the people, be they part of the salaried workers, the semi-peasants, enslaved people or even from bourgeois and petit-bourgeois sectors whose activities were harmed and/or suppressed by imperialist capital.

For example, the Japanese monopolized industry and completely dominated land ownership, in addition to imposing a cultural dictatorship, prohibiting Koreans from speaking their own language.

Thus, even some layers of the national bourgeoisie and petit-bourgeoisie found themselves compelled to fight against such obstacles to their own development as a class. The first major appearance of the working class occurred on March 1, 1919, when factories were occupied in a broad strike movement, followed by land occupations by peasants.

The impact of the First World War is noticeable, with the defeat of Japanese imperialism opening a crisis in its empire and, on the other hand, the Russian Revolution influencing the working class of several countries (and Korea borders Russia) in a revolutionary sense.

The March 1st Popular Movement, as it became known, had important consequences. The main one was to insert the proletariat once and for all as a protagonist on the political scene, paving the way for a qualitative leap in the Korean revolutionary national-democratic movement.

In 1925, the Communist Party of Korea was founded, which lasted only three years. Guided by the policy of the Third International, already controlled by Stalinism and whose erratic policy had imposed harsh defeats on the British and Chinese workers, this party did not rise to the occasion.

The Stalinist bureaucracy of the Soviet Union had manufactured the infamous theory of “socialism in one country”, a complete distortion of Marxism which, even in the times of its founders, defended the thesis of permanent revolution.

From the 1920s to the present day, the Stalinists and their successors preach the trust of the popular masses in the national bourgeoisie, handing over to them the leadership of the people in the struggle against imperialism.

But the national bourgeoisie, in times of imperialism, never tried – nor could it – fight imperialism to liberate its country. On the contrary: it prefers to hand over the country to imperialism rather than to its people.

This “revolution in stages” is nothing more than a pretext to boycott the international workers’ revolution, in collusion with imperialism to limit the scope of the revolution to just one or a very few countries.

As history has shown, this formula led to the total reflux and defeat of the revolution throughout the world. The theory of Permanent Revolution was first outlined by Karl Marx and taken up by Leon Trotsky in 1905, being further developed from the 1920s onwards.

This theory is a blunt response to the theory of “socialism in one country”, created by the right wing of the Bolshevik Party in the early 1920s and then elevated to the most grotesque level by the Stalinist bureaucracy.

According to Trotsky, in the imperialist phase of the development of society, the national bourgeoisie, even in countries where it does not completely dominate the economy, is not in a position to carry out a revolutionary struggle for democratic reforms, contrary to what it did in the previous period, leading the petit-bourgeois and popular masses to overthrow feudalism.

This revolution, which can be delimited in the historical period that goes from the 18th to the 19th century, occurred in Western Europe and North America, while the rest of the world, colonized by these powers, was prevented from developing in a complete way in that same sense.

This democratic task, therefore, in backward countries, where there has not been a bourgeois revolution or this has not been taken to its ultimate consequences, can only be reversed by the revolution of the workers supported by the peasants.

The Permanent Revolution, therefore, means a violent social transformation, which goes through the stage of democratic reforms of the bourgeois revolution but does not stop there, evolving into a socialist revolution. Always – contrary to what was proposed by the Stalinists – commanded by the working class in alliance with the peasantry, and never by the bourgeoisie.

In Trotsky’s words:

(…) the victory of the democratic revolution is only conceivable through the dictatorship of the proletariat supported by its alliance with the peasants and destined, first of all, to solve the tasks of the democratic revolution. (The Permanent Revolution, p. 206)

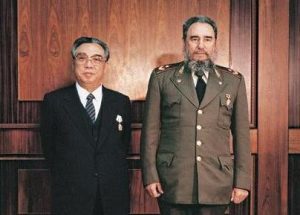

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 was the first proof of this theory. After it, many others came. A classic example is the Cuban Revolution of 1959, which was led by a movement (the M-26) with national-democratic aspirations, without initially expropriating the bourgeoisie.

However, faced with the needs of the revolution and pressure from the masses, Fidel Castro completely broke with the bourgeois sectors that had supported him and decreed, in 1961, the socialist character of the revolution.

However, the other side of the world had already provided new proof of the theory of Permanent Revolution, with the Vietnamese, Chinese and Korean revolutions.

Still in his work The Permanent Revolution, written almost 20 years before these revolutions, Trotsky stated: Given the acuteness of the agrarian problem and given the odious character of national oppression, the proletariat of colonial countries, despite its youth and relatively weak development, can come to power, placing itself on the ground of the national-democratic revolution, more sooner than the proletariat of an advanced country that places itself on a purely socialist terrain. (Idem, p. 180)

It was clear that the Korean revolutionary movement, to be successful, must be led by the working class, in alliance with the peasants and independent of bourgeois forces. A young man of just 14 years old would understand this and would take it upon himself to organize this independent movement in an armed struggle against imperialism.

——————————————————————————-

The Juche Idea and the meaning of independence for the Korean revolution

With the responsibility of organizing the vanguard of the Korean revolution, the young Kim Il Sung emerged, who would lead the process of establishing the dictatorship of the proletariat in Korea over the next seven decades. Instead of adhering to the policy of the Communist Party of Korea – an instrument of the Stalinist bureaucracy -, Kim Il Sung founded the Union to Defeat Imperialism (UDI: ㅌ.ㄷ.) in 1926, carrying out a policy independent of the Communist Party of the Third International.

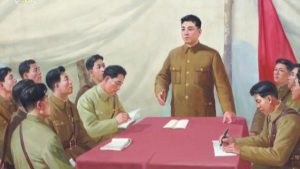

At the UDI founding ceremony, Kim Il Sung gave a speech in which he stated that:

Because the UDI assumes, in name and in fact, the mission of overthrowing imperialism, its program must establish the immediate task of destroying Japanese imperialism, the sworn enemy of the Korean people, achieving the liberation and independence of Korea, and maintaining as future task the building of socialism and communism in Korea, overthrowing all forms of imperialism and building communism throughout the world. (Let us overthrow Imperialism, October 17, 1926)

The idea of independence of the popular masses to carry out the revolution arises from Korea’s own colonial situation and from the struggles against other sectors of the revolutionary movement (such as the nationalists and the Communist Party).

The masses need to have class independence in relation to bourgeois nationalism, Stalinism and, obviously, imperialism. This idea will be further developed and will result in the official ideology of the North Korean Workers’ State, led by Kim Il Sung: the Juche philosophy.

It is a concept that means that it is necessary to rely on one’s own strengths, thus being a demarcation of ground between the movement that would lead the revolution and take power in North Korea and other sectors such as Korean nationalists and Stalinists, as well as, at the international level, an ideological support point for the political independence of the North Korean regime in relation to the Soviet bureaucracy.

In 1930, the Kalun Conference of the Communist Youth League and the Anti-imperialist Youth League took place. On this occasion, Kim Il Sung makes new statements about the permanent nature of the Korean revolution:

(…) The main task of the Korean Revolution, therefore, is to overthrow the Japanese imperialists and win Korean independence and, at the same time, liquidate feudal relations and introduce democracy. (…) We will not stop halfway in completing the anti-imperialist and anti-feudal democratic revolution, but we will transform it into a revolution to also build the socialist and communist society and thus carry out the world revolution. Completing the Korean Revolution is a great service to accelerating the world revolution. (The way forward for the Korean Revolution, June/July 1930)

Such a policy went against the dictates of Stalin’s Third International, which preached the “revolution in stages”, in which the democratic revolution should be supported by the proletariat but led by the bourgeoisie, to form a bourgeois regime that would carry out democratic reforms and, only then the proletariat could finally take power.

In the wake of this conference, an armed national liberation movement was formed, the Korean Revolutionary Army, which would later be called the Anti-Japanese People’s Guerrilla Army and, later on, the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army.

While Stalinism, at a global level, forced the communist movement that was under its influence to remain in the wake of the imperialist bourgeoisie in the infamous Popular Fronts, thus removing the class independence of the proletariat and adapting to bourgeois democracy, in Korea the revolutionaries took in arms to defeat imperialism and carry out the revolution.

What Kim Il Sung did, as did Fidel Castro later, was to lead the proletariat to lead the revolutionary process, relying first on the peasants and then on other sectors oppressed by Japanese imperialism, including layers of the petit bourgeoisie and the national bourgeoisie whose interests contradicted those of the occupants. But he never put the workers movement behind these sectors.

On the contrary: founded in 1936, the Association for the Restoration of the Fatherland was a united front whose main objective and result was the recruitment of hundreds of thousands of Koreans into the ranks of the revolution, being an impetus for the armed struggle, which was never abandoned by Kim Il Sung, thus opposing the general policy of Stalinism.

Regarding this process, Kim Jong Il (son of Kim Il Sung and his successor as leader of North Korea) reflected as follows:

Due to the fact that in the past our country was a backward, semi-feudal and colonial society, the working class was not numerous, but being the contingent with the strongest aspiration for independence and revolutionary spirit, it constituted the core of the forces of the revolution. Since the democratic, anti-imperialist and anti-feudal stage, the great Leader [referring to his father] considered the workers as members of the ruling class of the revolution and took their demands and those of the nation as the starting point of all his policies and guidelines. In our country, all processes of the revolution, from the anti-imperialist of national liberation and the democratic anti-feudal, to the socialist and its construction, were carried out successfully under the leadership of the working class. (Our socialism centered on the popular masses is invincible, May 5, 1991)

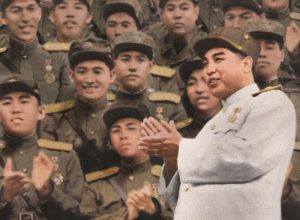

Thus, through this revolutionary process, which combined armed struggle in the mountains with the organization of the working class in the cities through Popular Committees, the communists led by Kim Il Sung took power in Korea in the wake of Japan’s defeat in World War II., in 1945.

Liberation of Korea: from democratic revolution to socialist revolution

The post-war revolutionary wave was something predetermined by the development of the contradictions of the imperialist system. Like World War I, World War II triggered a new revolutionary crisis, which took place especially in colonial countries, due to the brutal decline of the imperialist colonial regime.

Imperialist propaganda, to try to delegitimize the North Korean Workers’ State has always tried to say that the Korean Revolution was victorious because of the presence of the USSR Red Army, which entered the country in the final moments of the Japanese defeat in war.

In fact, when this occurred, the entire Korean Peninsula was full of People’s Committees, which led to the establishment of a duality of powers with the occupying forces and, finally, emerged victorious through the revolutionary uprising of the Korean people.

Independence was victorious with the revolution in the north, where the soldiers of the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army left. However, it was aborted in the south.

The Potsdam Conference established that the Soviet Union, when intervening in the Pacific War to help the United States defeat Japan, shared military operational activities in Korea with the North American imperialists (Ho, H. J.; Hui, K. S.; Ho, P. T. The U.S. imperialists started the Korean War, p. 39).

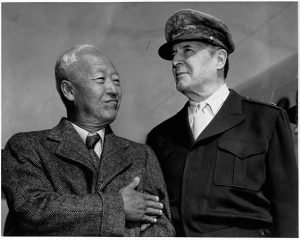

In practice, it was a capitulation by Stalin, since the U.S. clearly demonstrated that it intended to dominate Korea after defeating Japan, and the Soviets conciliated, allowing the military presence of the Americans in Korea, which opened the door to the subsequent intervention that occurred in South Korea, when General Douglas MacArthur imposed his puppet Syngman Rhee and, together with him and the Japanese collaborators who were pardoned, carried out a brutal suppression of the People’s Committees, preventing the revolution in south Korea and imposing a Fascist dictatorship over its people.

At the Yalta Conference, this agreement with Korea’s submission had already been indicated by the USSR, when Franklin Roosevelt stated that, “for Korea to become an independent country”, there would have to be a transition period of 40 years, which was ratified shortly afterwards (Idem, p. 67).

All of this without a policy of confrontation on the part of the Soviets, who soon demonstrated that they were truly willing to reconcile with imperialism in Asia. If the USSR defended a revolutionary policy, upon seeing U.S. troops invade southern Korea to decimate the revolution, the Red Army should intervene to support the revolution and guarantee Korea’s independence.

Thus, while the revolution was drowned in blood by imperialism without Soviet intervention in South Korea, North Korea experienced the beginning of its national-democratic revolution.

This had already been carried out gradually in some territories liberated by the revolutionary army and the People’s Committees (as had also occurred in the Chinese Revolution), but with the achievement of independence throughout the northern part and the seizure of power by the revolutionaries commanded by Kim Il Sung, this resulted in a gigantic leap.

In the chapter “The backward countries and the program of transitional demands” of the Transitional Program of the Fourth International, Trotsky analyzes that the central tasks of the democratic revolution in these countries are the agrarian revolution and national independence, which would directly result in the issues of the socialist revolution:

It is impossible to simply reject the democratic program: it is imperative that the masses themselves overcome it in the struggle. The slogan for a national (or constituent) assembly retains all its force in countries like India or China. This slogan must be inextricably linked to the problem of national emancipation and agrarian reform. The first step is to arm the workers with this democratic program. Only they can mobilize and unify the peasants. On the basis of the revolutionary democratic program, it is necessary to oppose the workers to the ‘national’ bourgeoisie. Thus, at a certain stage of mass mobilization under the slogans of revolutionary democracy, soviets can and must emerge. Their historical role, in each given period, in particular their relationship with the national assembly, will be determined by the political level of the proletariat, the link between it and the peasant class and the character of the policy of the proletarian party. Sooner or later, the soviets must overthrow bourgeois democracy. Only they are capable of leading the democratic revolution to a conclusion, thus opening an era of socialist revolution. (Transition Program, pp. 62-63)

Trotsky concludes that:

The dictatorship of the proletariat, which rises to power as the leading force of the democratic revolution, will inevitably and very quickly be faced with tasks that will lead it to make deep inroads into the bourgeois right to property. In the course of its development, the democratic revolution directly transforms into a socialist revolution, thus becoming a permanent revolution. (The Permanent Revolution, p. 208)

The democratic program consists of points such as the constituent assembly, the eight-hour working day, the confiscation of land, national independence from imperialism and the people’s right to dispose of themselves (Idem, p. 201).

The People’s Committees were the Korean equivalent of the soviets. If, in the south, they were violently crushed, in the north they were fundamental to the process that developed after independence. They formed the basis for the subsequent founding, in February 1946, of the Provisional People’s Committee of North Korea, the provisional revolutionary government.

This body was responsible for the promulgation, in the same year, of the laws on agrarian reform (March), labor (June), gender equality (July) and the nationalization of industries (August). That is, tasks of the bourgeois revolution carried out through the leadership of the working class, already in power of the State.

On October 10, 1945, Kim Il Sung also founded the new Communist Party, which created mass organizations such as the Peasant Union, the Youth Democratic League and the Women’s Democratic Union, in addition to the workers’ unions.

The National Democratic United Front was also founded with other parties supporting the revolution. This front was “based on the worker-peasant alliance led by the working class, and embracing the broad masses of people from all strata of social life” (Ho, H. J.; Hui, K. S.; Ho, P. T. The U.S. imperialists started the War of Korea, p. 85).

In August of the following year, the New Democratic Party (one of those who supported the revolution) joined the Communist Party, which was then renamed the Worker’s Party of Korea.

Leading the democratic reforms of the national revolution, the Workers’ Party decided to carry out the process that would trigger the formation of the Constituent Assembly. First, elections for People’s Committees were held in the districts, municipalities and provinces at the end of 1946.

Following this, the Congress of District, Municipal and Provincial People’s Committees was held in February 1947 in the capital Pyongyang, from which the North Korean People Committee was formed.

“This committee, which was a powerful weapon for socialist construction and revolution, strived to carry out the tasks of the period of transition to socialism and develop the national economy in a planned way,” Ho Jong Ho, Kang Sok Hui and Pak Thae Ho write (Idem, pp. 89-90).

At the end of 1947 and beginning of 1948, the Worker’s Party prepared the proposal to found the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea through democratic elections at national level.

At the same time, the puppet regime in South Korea, which continued to decimate the People’s Committees and suppress all democratic rights, guided by imperialism, sought to organize separate elections, meeting the aspirations of the Korean people for reunification.

Expressing the need to complete the national-democratic revolution, Kim Il Sung declares:

We must immediately establish a supreme legislative body throughout Korea, which represents the will of all the Korean people, and organize the Constitution of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. We should not establish it in a separate form, but in an all-Korea government consisting of representatives of political parties and social organizations from South and North Korea. (Idem, p. 94)

A first step towards these constituent elections was the Joint Conference of Representatives of South and North Korean Social Organizations and Political Parties, held in Pyongyang in April 1948, where 56 entities from across the country were represented.

The Conference called on all Korean people to boycott the separate and undemocratic elections (since all popular political organizations and parties were being outlawed) called by Syngman Rhee in the South.

Even so, the South Korean regime held openly fraudulent elections, imposing the founding of the Republic of Korea in the south on August 15.

This forced the revolutionaries to call general elections in the north and south to found a unified People’s Democratic Republic, in which 99.97% of North Korean voters and 77.52% of South Korean voters participated, despite strong repression from Seoul (Idem).

These elections gave rise to the Supreme People’s Assembly, the Korean constituent assembly, which promulgated a constitution and proclaimed the founding of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea on September 9, 1948.

However, despite giving national political legitimacy to the regime born of the People’s Committees, the Democratic People’s Republic could not consolidate itself throughout Korea, due to the division imposed by imperialism.

The Korean War and the mistakes of the Soviet government

Faced with growing threats of invasion of northern Korea by Syngman Rhee’s troops supported by the USA, in 1949 the Democratic Front for the Reunification of the Fatherland realized that the national-democratic revolution was still pending and launched a set of proposals for the independent reunification of Korea.

These proposals included reunification by Koreans themselves, the expulsion of imperialism, legalization of political parties and organizations in South Korea, and simultaneous general elections in the north and south that establish a supreme legislative body that promulgates a constitution, thus forming a unified government from all over Korea.

The response of the Seoul regime was to prepare, guided by imperialism, the invasion of the north to destroy the revolution once and for all.

Thus, on June 25, 1950, after several incursions north of the 38th Parallel (division formalized by imperialism in 1945 between the north and south of the peninsula), the Korean War finally began.

The Korean People’s Army, regularized in 1946, counterattacks and manages to push the South Korean army back to the 38th Parallel and beyond. If the war were only between North and South Korean forces, the Korean People’s Army would certainly win and liberate the entire Korean Peninsula, finally achieving reunification and the national-democratic revolution.

This was precisely the policy of the North Korean government, given the new situation imposed.

However, imperialism intervened militarily. Intervention plans had already been drawn up years before and the increase in the U.S. military presence in Japan and South Korea, as well as the U.S. participation in the provocations of Syngman Rhee’s army, signaled that war was imminent.

However, the USSR still maintained a belief in conciliation with imperialism in the East. Stalin himself was worried that the Chinese Revolution, victorious the previous year, would spark a revolution in neighboring countries that would displease imperialism (Marie, Jean-Jacques. Stalin, p. 842).

This is why the Soviets were caught with their pants down when the U.S. called an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council to approve the deployment of a joint military force to support South Korea against “aggression” from the North.

And that’s exactly what happened. The U.S. and 15 other armies invaded Korea to quell the revolution, this time also in the north. Among these 15 armies were those of France, Belgium and Greece, countries where, at the end of World War II, the working class was about to take power but was betrayed by Stalinism.

The Korean War showed the extent of the damage resulting from the Soviet bureaucracy’s policies to the international proletariat.

As stated above, if it were not for imperialist intervention, the North Korean government would have taken the revolution to the south and liberated the entire nation. It was about to do that.

Even in the first months of the war, the KPA occupied 90% of South Korea, where 92% of South Koreans lived, and there the northern revolutionaries restored the People’s Committees, founded Worker’s Party cells and carried out democratic reforms that had already been made in North Korea.

However, the landing of imperialist troops in September 1950 completely leveled the war and forced the KPA to retreat, demolishing the revolutionary structure that had been resumed, this time in an even more bloody manner.

The advance of 17 troops (South Korea, USA and the other 15 countries) reaches the 38th Parallel and surpasses it, invading North Korea and occupying almost all of its territory, with the exception of the northernmost mountains.

When imperialism was already showing signs of attempting an invasion of China itself, the revolutionary government that had taken power a year earlier in Beijing decided to organize the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, with one million men, to support the North Koreans and force the imperialists to return to the 38th Parallel again.

In turn, the Soviet Union did little to support the Korean revolutionaries. The Stalinist bureaucracy, in addition to governing the largest country in the world, bordering Korea and with a heightened prestige due to victory in World War II, controlled the governments of Eastern Europe and the communist parties of the West, many of them large mass parties.

It could have done many things, from sending the Red Army to organizing international brigades as he had done in Spain just over ten years earlier (which had already been an extremely bureaucratic, conservative and even reactionary undertaking in terms of results).

The USSR had already developed the atomic bomb in 1949 and could have used this power as a form of deterrence just when imperialism was already planning an attack against Korea. But he never did.

Thus, the North Koreans managed to force imperialism to sign a ceasefire in 1953, resuming the division of the peninsula from the 38th Parallel. If they had been helped by the Soviets, the revolution could have triumphed throughout Korea. But the Stalinist bureaucracy, decades ago, already showed total counter-revolutionary decadence.

North Korean foreign policy: a call for the union against imperialism

Despite the contradictions in the development of the revolution and the Korean Workers’ State, the North Koreans demonstrated countless times, throughout the second half of the 20th century, the validity of the theory of permanent revolution.

While the Soviet bureaucracy deepened the failed policy of “socialism in one country” with the doctrine of “peaceful coexistence” with imperialism and the continued boycott of the world revolution, the North Koreans preached an open struggle to abolish the imperialist system, starting with the domination of their own country by the vassal bourgeoisie.

They participated in the Tricontinental Conference which, in 1966 in Havana, founded the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL) with the aim of expanding the revolution to the entire globe.

Backward countries, whose revolutionary movements had greater independence from the Soviet bureaucracy (unlike Europe) were encouraged to take up arms to wage the struggle for national liberation, democratic revolution and socialism.

In an article for Tricontinental Magazine, Kim Il Sung expresses such a policy that is completely opposed to Moscow’s dictates, stating:

It is a mistake to try to avoid the fight against imperialism by claiming that, although independence and revolution are good, peace is more precious. Is it not a real fact that the line of an unprincipled compromise with imperialism only encourages its aggressive maneuvers and increases the danger of war? A peace that leads to slave submission is not peace. True peace cannot be achieved if we do not fight against those who disturb it and if we do not destroy the domination of the oppressors by opposing this slave-owning peace. In the same way that we oppose the line of compromise with imperialism, we cannot admit the fear of fighting against imperialism with practical actions, limiting ourselves only to loudly proclaiming that we are against imperialism. This is nothing but the opposite of the compromise line. Both have no resemblance to the true anti-imperialist struggle and only serve as an aid to imperialism’s policy of aggression and war. (Let us strengthen the anti-imperialist and anti-Yankee struggle, August 12, 1967)

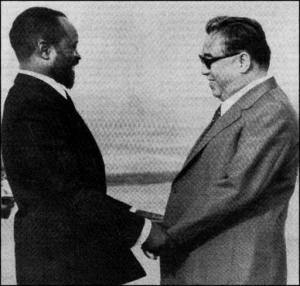

[Salvador Allende shakes hands with North Korean leader Kim Il Sung during his visit to the country in 1969, a year before he was elected president of Chile | Image: Public domain, edited by NK Pro]

[Salvador Allende shakes hands with North Korean leader Kim Il Sung during his visit to the country in 1969, a year before he was elected president of Chile | Image: Public domain, edited by NK Pro]

The North Korean leader also writes, in the same article:

The anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist struggle of the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America is a sacred struggle for the liberation of hundreds of millions of oppressed and exploited human beings and, at the same time, a great struggle aimed at cutting off this lifeline from world imperialism. This struggle constitutes, together with the revolutionary struggle of the working class for socialism, the two great revolutionary forces of our time, which have come together to form a single current that buries imperialism. (Idem)

Throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, the North Koreans sought to put this thought into practice, providing military training and sending troops and weapons to revolutionaries in several backward countries, including Angola, Mozambique and Brazil.

This support was much greater than that of the Soviet bureaucracy, which was not concerned with the revolution, but rather with controlling the governments resulting from these revolutions so that they, instead of deepening the revolutionary process, served as satellites to serve political and economic interests of the USSR.

Contrary to the Stalinist theory of the camps, the North Koreans understood that the class struggle at a global level is not synthesized in the struggle of the “socialist camp” against the “capitalist camp”, but rather in the struggle of oppressed peoples against imperialism.

The fight against imperialism within Korea, to this day, is also fought following these same principles.

Correctly, North Korea’s demands for reunification with the South are based on the needs of the national-democratic revolution, since, despite having established the dictatorship of the proletariat in the North, the South continues to be controlled by imperialism and a dictatorship against the working class.

Therefore, the struggle for national liberation is still ongoing, which, in essence, has a national-democratic character in the South.

Learning from their own experience of the national-democratic revolution and the anti-imperialist war, the North Koreans came to that conclusion eternalized in the words of Che Guevara: “You can’t trust imperialism, but that’s it, nothing!”

On the other hand, decades of struggle against erroneous tendencies within his own country, from the founding of the UDI in opposition to the Stalinist communist party, through the national liberation revolution that contradicted the Soviet bureaucracy’s policy of conciliation with imperialism and reaching during the Korean War in which they did not receive the necessary support from the USSR, the North Koreans learned that it was necessary to maintain political independence in relation to the Stalinist clique.

They even openly criticized the Soviet bureaucracy, denouncing it for boycotting the world revolution, as in this statement by Kim Jong Il:

The socialist cause of a people is national and, at the same time, international. The communist party or the workers of each nation have the right to defend their independence and, at the same time, the obligation to respect that of the parties of other States, and to unite and collaborate based on comradeship for the cause of socialist victory. (Historical lessons in the construction of socialism and the general line of our Party, January 3, 1992)

Still in this speech, Kim Jong Il makes a scathing criticism of the rigging of Eastern European communist parties by the Soviet bureaucracy:

There had long been a center in the international communist movement, and each country’s party acted as its branch. The natural thing would have been for the parties of the socialist countries to cooperate on the basis of complete equality and independence, but some, by not having freed themselves from the customs contracted in the midst of their old relations, during the time of the Communist International, caused great damage to the advancement of the international communist movement. One, calling himself the ‘center’, had shamelessly perpetrated acts of transmitting orders to others and pressuring and intervening in the internal affairs of those who did not follow his mistaken line. (Idem)

Certainly, the fact that it was carried out independently of Stalinism and that it maintained this independence is one of the causes of the permanence of the North Korean Workers’ State, even after the fall of the USSR and the Eastern European regimes and the capitalist restoration in Asia.

Perhaps the greatest merit of Kim Il Sung, who passed away in 1994, was taking the revolution forward at the exact moment it was being boycotted by the Stalinist bureaucracy worldwide.

Contrary to what bar Stalinists may think, North Korea is not proof of the theory of “socialism in one country”, but rather of the need for permanent revolution. Socialism, as a superior form of organization of society and as a political and economic system, can only be fully achieved when the imperialist system has been overcome.

In a world controlled by imperialism, where all social relations are dominated or at least influenced by this regime, it is not possible to achieve complete independence, as the North Korean example itself demonstrates.

The post-USSR isolation with the cruel imperialist economic blockade produced more than a decade of hunger for millions of Koreans and even today, when this situation is better controlled, the country still suffers from numerous difficulties caused by economic sanctions and constant military threats.

Furthermore, the semi-colonial rule of imperialism over South Korea stopped the national-democratic revolution of the Korean people. It will only conclude with the liberation of South Korea and the reunification of the entire peninsula independently of imperialism.

By Eduardo Vasco

Published by SCF

II

Eduardo Vasco continues to explain how Kim Il Sung managed to create a Communist regime largely independent of the Soviet Union.

With the responsibility of organizing the vanguard of the Korean revolution, the young Kim Il Sung emerged, who would lead the process of establishing the dictatorship of the proletariat in Korea over the next seven decades.

Instead of adhering to the policy of the Communist Party of Korea – an instrument of the Stalinist bureaucracy – Kim Il Sung founded the Union to Defeat Imperialism (UDI) in 1926, carrying out a policy independent of the Communist Party of the Third International.

At the UDI founding ceremony, Kim Il Sung gave a speech in which he stated that:

Because the UDI assumes, in name and in fact, the mission of overthrowing imperialism, its program must establish the immediate task of destroying Japanese imperialism, the sworn enemy of the Korean people, achieving the liberation and independence of Korea, and maintaining as future task the building of socialism and communism in Korea, overthrowing all forms of imperialism and building communism throughout the world. (Let us overthrow Imperialism, October 17, 1926)

The idea of independence of the popular masses to carry out the revolution arises from Korea’s own colonial situation and from the struggles against other sectors of the revolutionary movement (such as the nationalists and the Communist Party). The masses need to have class independence in relation to bourgeois nationalism, Stalinism and, obviously, imperialism.

This idea will be further developed and will result in the official ideology of the North Korean Workers’ State, led by Kim Il Sung: the Juche philosophy.

It is a concept that means that it is necessary to rely on one’s own strengths, thus being a demarcation of ground between the movement that would lead the revolution and take power in North Korea and other sectors such as Korean nationalists and Stalinists, as well as, at the international level, an ideological support point for the political independence of the North Korean regime in relation to the Soviet bureaucracy.

In 1930, the Kalun Conference of the Communist Youth League and the Anti-imperialist Youth League took place. On this occasion, Kim Il Sung makes new statements about the permanent nature of the Korean revolution:

(…) The main task of the Korean Revolution, therefore, is to overthrow the Japanese imperialists and win Korean independence and, at the same time, liquidate feudal relations and introduce democracy. (…) We will not stop halfway in completing the anti-imperialist and anti-feudal democratic revolution, but we will transform it into a revolution to also build the socialist and communist society and thus carry out the world revolution. Completing the Korean Revolution is a great service to accelerating the world revolution. (The way forward for the Korean Revolution, June/July 1930)

Such a policy went against the dictates of Stalin’s Third International, which preached the “revolution in stages”, in which the democratic revolution should be supported by the proletariat but led by the bourgeoisie, to form a bourgeois regime that would carry out democratic reforms and, only then the proletariat could finally take power.

In the wake of this conference, an armed national liberation movement was formed, the Korean Revolutionary Army, which would later be called the Anti-Japanese People’s Guerrilla Army and, later on, the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army.

While Stalinism, at a global level, forced the communist movement that was under its influence to remain in the wake of the imperialist bourgeoisie in the infamous Popular Fronts, thus removing the class independence of the proletariat and adapting to bourgeois democracy, in Korea the revolutionaries took in arms to defeat imperialism and carry out the revolution.

What Kim Il Sung did, as did Fidel Castro later, was to lead the proletariat to lead the revolutionary process, relying first on the peasants and then on other sectors oppressed by Japanese imperialism, including layers of the petit bourgeoisie and the national bourgeoisie whose interests contradicted those of the occupants. But he never put the workers movement behind these sectors.

On the contrary: founded in 1936, the Association for the Restoration of the Fatherland was a united front whose main objective and result was the recruitment of hundreds of thousands of Koreans into the ranks of the revolution, being an impetus for the armed struggle, which was never abandoned by Kim Il Sung, thus opposing the general policy of Stalinism.

Regarding this process, Kim Jong Il (son of Kim Il Sung and his successor as leader of North Korea) reflected as follows:

Due to the fact that in the past our country was a backward, semi-feudal and colonial society, the working class was not numerous, but being the contingent with the strongest aspiration for independence and revolutionary spirit, it constituted the core of the forces of the revolution. Since the democratic, anti-imperialist and anti-feudal stage, the great Leader [referring to his father] considered the workers as members of the ruling class of the revolution and took their demands and those of the nation as the starting point of all his policies and guidelines. In our country, all processes of the revolution, from the anti-imperialist of national liberation and the democratic anti-feudal, to the socialist and its construction, were carried out successfully under the leadership of the working class. (Our socialism centered on the popular masses is invincible, May 5, 1991)

Thus, through this revolutionary process, which combined armed struggle in the mountains with the organization of the working class in the cities through Popular Committees, the communists led by Kim Il Sung took power in Korea in the wake of Japan’s defeat in World War II., in 1945.

By Eduardo Vasco, a Brazilian journalist specializing in international politics.

Published by SCF

[Editor’s note: Photos selected for the original SCF article were compiled by The 21st Century.]

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.com