II. Origins and causes of the Korean War

By the 20th century, Korea had been a singular political entity for one thousand years. It was a highly cultured state, infused with Buddhist and Confucian traditions, in which the world’s first printing press was invented. Following invasions by the Mongols and Japanese in the 16th century, Korea became known as the “hermit kingdom” for its strong isolationist policy. In 1897, King Gojong, proclaimed the founding of the Greater Korean Empire, effectively severing Korea’s historic ties as a tributary of Qing China.[16] The country was thus sovereign and unified on the eve of the Japanese conquest in the early 20th century. With the departure of the Japanese in 1945, expectations for a unified, independent Korean nation were undermined by rival nationalist leaders and their powerful foreign patrons.

Backdrop of Japanese colonialism

The Korean War’s origin is rooted in the era of Japanese colonialism. Japan had colonized Korea in 1910 under the Pan-Asian doctrine, claiming that its destiny was to help uplift Asia and prevent Western colonial exploitation. Emulating the practices of the West, the Japanese built up Korea’s transportation infrastructure and nascent industrial capacities, while promoting divide and rule tactics by ruling through native collaborators among the old bureaucracy and landed elites. The system was marked by pronounced social inequality, labor exploitation, rural poverty, and draconian police tactics.

Japanese oppression prompted the growth of nationalist opposition which by the 1930s was predominantly led by communists, as in Vietnam. Historian Dae Suk Suh notes that “for Koreans, the sacrifices of the communists, if not the idea of communism, had strong appeal. . . . The haggard appearance of the communists suffering from torture, their stern and disciplined attitude towards the common enemy of all Koreans [Imperial Japan], had a far reaching effect on the people.”[17]

Following the Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931, the communists spearheaded anti-Japanese guerrilla operations under the banner of the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army, which bogged down Japan’s Kwantung Army. The Japanese engaged in “bandit suppression” activities that included the denial of food to rebel base areas.

Kim Il-Sung emerged in this milieu as a prominent guerrilla commander adept at unifying disparate factions and mixing nationalism with revolution. His most famous exploit was a raid on Poch’onbo, a Korean town across the border in Manchuria where he led almost two hundred guerrillas on June 4, 1937, in destroying local government offices and setting fire to the Japanese police station. Kim was hunted by a special “Kim II-Sung Activities Unit” of the Japanese, which was made up of fifty pro-Japanese Korean soldiers commanded by Kim Sok-Won, a colonel decorated by the Emperor Hirohito who later became prominent in the American-backed Republic of Korea Army. Kim Sok-Won resumed his role in targeting Kim Il-Sung after the Korean War broke out in 1950.[18]

The redrawing of old battle lines exemplified the colonial origins of the Korean War, with the revolutionary supporters fearing the restoration of Japanese domination in Korea. Reinforcing these sentiments, Japan actually provided military assistance to South Korea during the war, hedging on violation of international agreements stipulating its demilitarization. It contributed minesweepers to clear Inchon harbor ahead of General Douglas MacArthur’s invasion and naval vessels along with other logistical support. At least twenty-one Japanese perished during the Korean War and one was taken prisoner.[19]

American imperial ambitions

Japanese rule formally came to an end in Korea in September 1945. At the Potsdam conference in late July, Allied leaders failed to agree on a plan for administering Korea after the surrender of the Japanese. President Truman hoped that the Japanese would surrender before the Soviet Union entered the war in Asia, thus giving the U.S. and Great Britain a free hand in reconstructing governments in Korea, Japan, and China in the postwar period.

However, the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan on August 9, 1945, the same day that the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki. The following day, Secretary of State James Byrnes directed the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee to draw up a proposal for dividing Korea into separate zones controlled by the Soviet Union and the United States. The committee delegated the task to Colonels C. H. Bonesteel and Dean Rusk, who drew the line at the 38th parallel.

The proposal was designed to limit the Soviet advance into Korea, as Soviet troops were poised on the Korean border and U.S. troops were 600 miles away. Surprisingly, Stalin accepted the proposal, no doubt expecting his compromise to be reciprocated in other matters. Soviet troops entered Korea on August 12 and occupied Pyongyang on August 24. Two weeks later, on September 8, U.S. forces arrived in southern Korea.

The former World War II allies each put into place a government that maintained close ties with its foreign patron. As the Cold War intensified, the idea of forming a unified Korean government faded; or put another way, both the South and North Korean governments sought to unify the country under their own authority. The Chinese revolution, which pitted the U.S.-backed forces of Jiang Jieshi against the Soviet-backed forces of Mao Zedong, exacerbated tension.

Mao’s victory in October 1949 raised fears in the U.S. that communism would sweep across Asia. By this time, both U.S. and Soviet troops had been officially withdrawn from Korea. Yet a sizable group of U.S. military advisors remained to train and participate in South Korean counterinsurgency operations; while in North Korea, Soviet advisers remained at least to the battalion level and possibly as far down as company level.

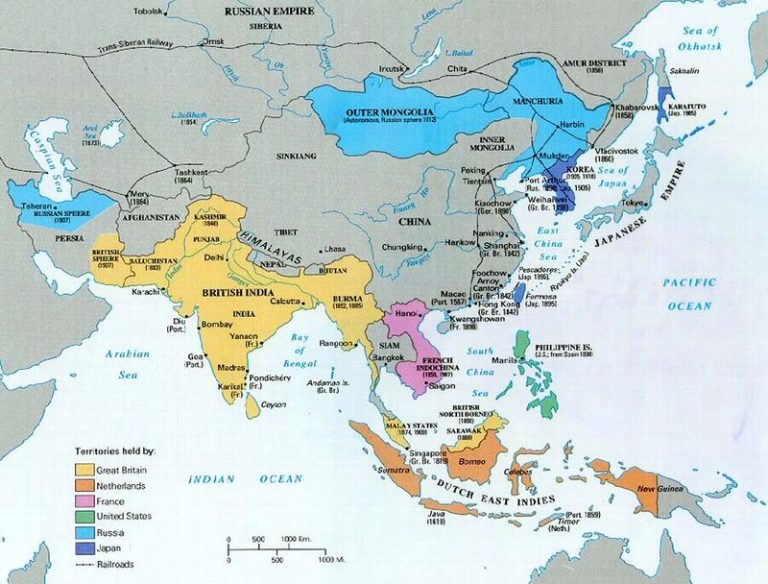

Japan and the U.S. both entered the imperial competition in Asia at the turn of the 20th century, Japan in Korea and the U.S. in the Philippines. Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Russia had already established control over large areas of Asia.

Beyond occupying South Korea at the end of World War II, U.S. involvement in Korea was a consequence of the long American drive for power in the Asia-Pacific region dating to the seizure of Hawaii and conquest of the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century. This mission was motivated by a trinity of military, missionary, and business interests. After the defeat of Japan in World War II, the prospect opened up that the region could come under U.S. influence, its rich resources tapped for the benefit of American industry.

In a March 1955 Foreign Affairs article, William Henderson of the Council on American Foreign Relations (which Laurence Shoup and William Minter aptly termed the “imperial brain trust”) wrote: “As one of the earth’s great storehouses of natural resources, Southeast Asia is a prize worth fighting for. Five sixths of the world’s rubber, and one half of its tin are produced here.

It accounts for two thirds of the world output in coconut, one third of the palm oil, and significant proportions of tungsten and chromium. No less important than the natural wealth was Southeast Asia’s key strategic position astride the main lines of communication between Europe and the Far East.”[20] To secure access to these resources, the U.S. established a chain of military bases from the Philippines through the Ryukyu Archipelago in southern Japan.

The victory of the communists in the Chinese revolution cut off American access to the vast China market and shattered longstanding American dreams of bringing China into the American sphere of influence. The revolution also represented an ideological challenge in advancing the Russian model of state-driven socialist industrial development as an alternative to Western capitalism. Since the 1930s, the United States had been committed to Chinese nationalist leader Jieng Jieshi as a bulwark of an American dominated Asia. The U.S. continued to support Jieng after he violently consolidated his power as leader of Taiwan and co-founded the People’s Anti-Communist League with Syngman Rhee.[21]

For the American right, the “loss of China” was a devastating blow, prompting the embrace of an Asian-centric rollback policy.[22] Supporters of this policy, including mid-western Republican Senators Robert Taft of Ohio and Kenneth Wherry of Nebraska, considered Asia as a place where the U.S. could extract minerals and gain profit while spreading American and Christian ideals. Their vision dovetailed with that of free-enterprise liberals who believed in the American mission to promote free-trade and development in the backwards regions of the globe. They feared China’s obtaining a great-power status capable of allowing it to challenge an Asian system shaped by America.[23]

Japan was the super-domino in the postwar containment strategy. American leaders were committed to rebuilding Japan along capitalist lines in part by opening up regional markets. This policy gained greater urgency as a result of the Chinese revolution of 1949, whose primary goal was to escape the yoke of Japanese and Western neocolonialism by spearheading industrialization and implementing land reform and collectivized agriculture along with programs of uplift for poor peasants.[24]

State Department internationalists pushed for connecting South Korea’s economy to Japan’s, in part to enable Japan to extract raw materials capable of sustaining its economic recovery, and in part to keep Japan in the Western orbit as a counterweight to communist China. In January 1947, Secretary of State George Marshall scribbled a note to Dean Acheson: “Please have plan drafted of policy to organize a definite government of So. Korea and connect up its economy with that of Japan.”[25] The war ultimately served as a great boon to Japan’s economy and the U.S. acquired military bases in South Korea that are still in its possession today.

The communist victory in China also led the Truman administration to supply military aid to the French in Vietnam beginning in February 1950. Although couched in the language of anti-communism and protection of the “free world,” it became clear to many in the “Third World” that the U.S. had chosen to align with (French) imperialism against the rising tide of nationalist revolutions in Asia and Africa.

Social revolution and repression in North Korea

Many Koreans yearned for a major social transformation following the era of Japanese colonial rule and, like other people in decolonizing nations, looked to socialist bloc countries as a model. Americans, unfortunately, were conditioned to view the world in Manichean Cold War terms and thus never developed a proper understanding for the appeal of revolutionaries such as Kim Il Sung.

North Korea experienced a genuine social revolution in the years 1945-1950, which was driven from the top down as well as the bottom up. The liberating aspects of this social revolution, however, were compromised by the establishment of a repressive police state as well as a personality cult around Kim II-Sung, much like those surrounding Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong. Still, North Korea was not the puppet of the Soviet Union or China that Americans imagined.

As the Soviet Union occupied North Korea Kim Il-Sung consolidated his position as the “great leader” of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Kim Il Sung joined the Communist Party of Korea in 1931 and, as previously noted, earned a measure of fame for spearheading nationalist resistance to Japanese rule in Manchuria during the 1930s. After being pursued by the Japanese in Manchuria, Kim Il Sung escaped to the Soviet Union and became an officer in the Red Army during World War II. He returned to Korea in September 1945 and, with Soviet backing, established himself as the North Korean leader. He gained Mao Zedong’s support by recruiting a cadre of guerrillas to aid communist forces in the Chinese civil war.

The Soviet Union’s main interest in Korea was in seeking access to warm water ports and a friendly regime as a buffer against Japan. Soviet soldiers, like most occupying armies, abused the local population, in some instances committing rapes. Their presence, however, was confined predominantly to the capital, Pyongyang. Soviet advisers helped draft a new constitution, sponsored cultural exchanges and programs, and guided certain reforms and foreign policy. North Koreans nonetheless asserted considerable autonomy and many looked to Russia and China as countries which were rapidly industrializing and had empowered the peasantry and masses by moving to abolish class distinctions.

Embracing state socialism as a means of “skipping over centuries of slavery and backwardness,” the Kim regime adopted an economic ideology centered on the concept of “juche,” or self-reliance, which helped to jumpstart economic development.[26] At the time of Korea’s liberation, over 90 percent of the industry in the former colony was owned by Japanese interests. The material resources for an egalitarian revolution were thus available. With the Japanese deposed, workers committees led predominantly by communists took control of most of the factories in the North. For a brief period, the Soviets seized control of the economy, including of the Wonsan Oil Company, and sent equipment, parts and the raw materials (including the oil) back to Russia as a “war prize.”

After the North Korean People’s Committee was established in February 1946 , North Koreans retook charge and promulgated a law on nationalization of major industries which resulted in more than one thousand industries (90 percent of all of them in the North including electricity, transportation, railways and communications) becoming state property. By 1949, more than 50 percent of state revenue came from these nationalized industries, which helped finance the building of road infrastructure, schools and politicized universities as well as hospitals. The funds were also used to create a literacy program that reached over two million farmers.[27]

The DPRK’s crowning achievement was an expansive land reform campaign that was far less bloody than its counterparts in China and North Vietnam. According to U.S. Army intelligence, the land reform program “made 70 percent of the peasants’ ardent supporters of the regime,” although this total would later drop because of onerous taxation. Under the terms of the March 5, 1946 land reform law, all land owned by the Japanese government and Japanese nationals was confiscated along with land belonging to Korean landlords in excess of five chongbo (roughly twelve acres) and land rented out by landlords. Debts were also canceled. Nearly all of the confiscated land, which amounted to 980,000 chongbo, was redistributed to 710,000 peasant households for free, with less than 2 percent kept under state ownership. North Korea thus created a socialist economy in which major industries were under state control while most land was held by private households.

Based on the Maoist ideal of a society organized on the basis of collective social needs, Kim’s regime gained further support by promoting labor laws limiting working hours and providing collective bargaining rights as well as advancing women’s rights, passing laws to secure free rights in marriage and outlawing dowry exchange and child marriage. An editorial in a local newspaper asserted in 1947 that the “life of a North Korean woman today has been completely freed from subordination, domination, subservience and exploitation.”

Suzy Kim, in Everyday Life in the North Korean Revolution, 1945-1950, points to the importance of the people’s committees set up after liberation in spearheading revolutionary transformation. Though Kim Il Sung refused a UN supervised general election in the North in 1948, local elections were held for positions in which participation was high. Lt. Col. Walter F. Choinski, who was stationed in P’yongyang, likened them to the early 1900s in the U.S. in the level of excitement. He and other observers reported that the results were contested and that village meetings vetted candidates, ensuring that those who stood for office were popular and respected.[28] DPRK legitimacy was also bolstered after its formation through a purge of Japanese police officers linked to human rights atrocities.

The DPRK invested considerable resources into education, propaganda and culture as an important vehicle in mobilizing support for the regime. Over one hundred writers had migrated from the South. Outside observers spoke of a “cultural renaissance” of native folk dancing, music, literature and drama. A nascent film industry was developed that celebrated the nationalist struggle against Japan. In late 1949, Kim Il Sung called on writers and artists to be “warriors who educate the people and defend the republic” and most importantly “portray the heroic struggle of the working people.” Pyongyang journalist Han Chaedok and novelist Han Sorya helped create a cult of personality surrounding Kim, modeled after Stalin and Mao. It proved to be long-lasting because it drew on Neo-Confucian tradition entailing respect for familial loyalty.

The North Korean government also relied on authoritarian measures and repression of dissent, confirming the West’s negative view of it in this regard. The Kim II-Sung regime developed a siege mentality that demanded unity in the face of the threat of outside subversion.[29] The DPRK created a draconian surveillance apparatus, purging political rivals to Kim and his clique. On November 23, 1945, in Sinuiji, security forces gunned down Christian student protesters in front of the North P’yongan provincial office; and later some three hundred students and twenty Christian pastors were arrested after further anticommunist demonstrations.

American intelligence concluded that the “nucleus of resistance of the Communist regime are the church groups, long prominent in North Korea, and secret student societies. Resistance was centered in the cities, notably Pyongyang, and took the form of school strikes, circulation of leaflets, demonstrations and assassinations. The government replied with arrests and imprisonments, investigations of student and church groups, and destruction of churches.”[30] Christians as well as business and land owners faced with the confiscation of their property began fleeing to the South. With deep grievances against communism, these refugees provided a backbone of support for the Syngman Rhee government. Many served in right-wing youth groups, modeled after fascist style organizations, which violently broke up workers demonstrations and assaulted left-wing political activists. [31]

In June 1949, North Korea accelerated its “peace offensive” toward the South, calling for all “democratic” – that is anti-Syngman Rhee forces – to join with the North in unifying the Korean peninsula and removing the Americans. It pushed for free elections in which left wing political parties in the South were legalized and political prisoners released. According to the historian Charles K. Armstrong, in The North Korean Revolution, 1945-1950, a free political environment would have given the left an estimated 80 percent of the vote in the North and 65-70 percent of the votes in the South. Kim and his allies could thus come to power through democratic means had the popular uprising in the South not been repressed.[32]

The North Korean People’s Army (KPA) grew directly out of the public security organizations developed after liberation. According to Armstrong, the Kim regime required little coercion in recruiting youth between the ages of eighteen to twenty five for enlistment, with most enlistees drawn from families of workers and poor peasants who supported the regime. The Fatherland Defense Association organized in July 1949 encouraged citizens to support the military as part of a process of mass mobilization for war that American leaders grossly underestimated.[33]

Kim’s Manchurian cronies were placed at the head of the KPA and all Korean officers who had served the Japanese military were purged officially by June 1948. Soviet advisers remained after 1948, and the Soviets provided vintage World War II weaponry including tanks and aircraft. The connection to the Chinese Red Army was more intimate than to the Soviets though, as U.S. military intelligence estimated that at least 80 percent of the officers of the security forces were former members of the Korean Volunteer Army from the Chinese front, and at least half of North Korean soldiers in the KPA were veterans of China’s civil war. The victory of the Chinese communist forces in October 1949 resulted in the return of thousands of troops to North Korea. U.S. military intelligence said that “these experienced troops made the KPA a much more effective fighting force than it would otherwise have been.”

Brutal anti-communist pacification in South Korea

Syngman Rhee was a conservative nationalist who lived in the United States for over four decades after being imprisoned by the Japanese as a young man. The Truman administration brought him back to Korea in October 1945 to lead the new South Korean government. Considering him a “Jeffersonian democrat,” the U.S. Office of Strategic Services believed that Rhee harbored “more of an American point of view than other Korean leader.”[34]

In practice, Rhee exhibited strong autocratic tendencies and relied heavily on Japanese collaborators – in part because he had been out of the country so long. He was elected president in July 1948 by members of the National Assembly, who themselves had been elected on May 10 in a national election marred by boycotts, violence and a climate of terrorism. The elections were originally intended to be held in both the North and South, but Kim II-Sung refused to allow UN supervisors entry into North Korea. Some South Koreans boycotted the elections on the grounds that they would solidify the division between the Koreas, which is indeed what happened. Syngman Rhee proceeded to consolidate his rule thereafter. When asked by the journalist Mark Gayn whether Rhee was a fascist, Lieutenant Leonard Bertsch, an adviser to General John R. Hodge, head of the American occupation, responded, “He is two centuries before fascism—a true Bourbon.”[35]

After formal establishment of the Republic of Korea (ROK) on August 15, 1948, Rhee refused to accept power sharing proposals to unify the north and south. Rhee also reinforced the economic status quo. According to Bruce Cumings, “The primary cause of the South Korean insurgency was the ancient curse of average Koreans – the social inequity of land relations and the huge gap between a tiny elite of the rich and the vast majority of the poor.” At the same time Rhee followed American dictates in passing a secret clause agreeing to export rice to Japan and signed contracts allowing American businesses to exploit the So Lim gold mine and take over the Sandong tungsten mine, which was guarded by U.S. troops.[36]

Political opposition to Rhee’s government emerged almost immediately when Rhee, with U.S. backing, retained Japanese-trained military leaders and police officers instead of removing them. Those who had resisted Japanese rule, administered with the aid of these collaborators, called for Rhee’s ouster. The communists in South Korea protested the loudest, as they had led the anti-Japanese insurrection, but opposition to Rhee was widespread. Resistance to the U.S. occupation and Rhee’s government was led by labor and farmers’ associations and People’s Committees, which organized democratic governance and social reform at the local level.

The mass-based South Korean Labor Party (SKLP), headed by Pak Hon-Yong, a veteran of anti-Japanese protest with communist ties, led strikes and carried out acts of industrial sabotage.[37] Rhee responded by building up police and security forces and, with assistance from the American Military Government (AMG), attempting to eliminate all political opposition, which he labeled communist-backed. Thus, the earlier antagonism between rebels and collaborators during Japanese rule took on the dimensions of both a partisan struggle within South Korea and a struggle between North and South.

In October 1946, revolts broke out in South Cholla province, triggered by police abuse and the imposition of strict wage controls by occupation authorities. Riots in Taegu were precipitated by police suppression of a railroad strike that left thirty-nine civilians dead, hundreds wounded, and thirty-eight missing. Martial law was subsequently declared and 1,500 were arrested. Forty were sentenced to death, including SKLP leader Pak, who fled North.

Over 100,000 students walked out in solidarity with the workers, while mobs ransacked police posts, buried officers alive, and slashed the face of the police chief, in a pattern replicated in neighboring cities and towns. Blaming the violence on “outside agitators” (North Korean support was in fact more moral than material) and the “idiocy” of the peasants, the American military called in reinforcements to restore order. The director of the U.S. Army’s Department of Transportation stated: “We had a battle mentality. We didn’t have to worry too much if innocent people got hurt. We set up concentration camps outside of town and held strikers there when the jails got too full…. It was war. We recognized it as war and fought it as such.”[38]

By mid-1947, there were almost 22,000 people in jail, nearly twice as many as under the Japanese, with the Red Cross pointing to inadequate medical care and sanitation. Professors and assemblymen were among those tortured in custody. Those branded as communists were dehumanized to the extent that they were seen as unworthy of legal protection. Pak Wan-so, a South Korean writer who faced imprisonment and torture by police commented that “they called me a red bitch. Any red was not considered human…. They looked at me as if I was a beast or a bug…. Because we weren’t human, we had no rights.”[39] The scale of repression in South Korea at this time far surpassed that of North Korea. In Mokpo seaport, the bodies of prisoners who had been shot were left on people’s doorsteps as a warning in what became known as the “human flesh distribution case.”[40] A government official defended the practice saying they were the most “vile of communists.”

Gordon Young who later worked for the CIA in Thailand spoke of a massacre by American troops at a checkpoint “comparable to the Calley incident in Vietnam.” (U.S. Lieutenant William Calley was held responsible for the My Lai massacre in which 500 civilians were killed.) The main culprit was fined one dollar and transferred out of his unit as penalty. “Nobody worried about adverse publicity in those days…. There is a distinct habit among elements of American GIs for becoming absolute slobs when away from home and society. Some of course came from backgrounds of bad upbringing and even criminal elements.”[41] Young’s comments underscore the climate of impunity in which U.S. soldiers operated and the lack of public concern for the fate of Korean civilians within the post-World War II victory culture of the United States.[42]

To assist in pacification, the AMG developed a police constabulary which provided the foundation for the Republic of Korea Army (ROKA). Building on colonial precedents in Nicaragua and the Philippines, the constabulary wore American supplied uniforms, carried American arms, and moved with American transport, with its eight divisions plus a cavalry regiment recapitulating the American military model. Soldiers were valued for their knowledge of the local terrain and ability to tell “the cowboys from the Indians,” as legendary Marine commander Lewis “Chesty” Puller put it.[43] The chief adviser, Captain James Hausman, provided instruction in riot control and psychological warfare techniques such as dousing corpses of executed people with gasoline so as to hide the manner of execution or blame it on the communists.

The ROKA gained valuable experience suppressing guerrilla rebellions in the Chiri-San mountains and on the southern island of Cheju-do in 1948, where units operated under U.S. military command. They were aided by aerial reinforcements and spy planes that swept over the mountains, waging “an all-out guerrilla extermination campaign,” as Everett Drumwright of the American embassy characterized it. A third of the population in the region was forcibly relocated and tens of thousands were killed, including guerilla leaders Yi Tôk-ku, whose mutilated corpse was hung on a cross, and Kim Chi-hoe, whose head was shipped to Capt. Hausman’s office in Seoul.[44]

Similar brutality was displayed in the suppression of a popular insurrection in Yeosu which broke out in October 1948 after the 14th ROKA regiment refused orders to “murder the people of Cheju-do fighting against imperialist policy.”[45] Order was restored only after purges were enacted in the constabulary regiments that had mutinied under Hausman’s direction and the perpetrators were executed by firing squad. Much of the town was set on fire.[46]

On April 14, 1950, ten miles northeast of Seoul, South Korean Military Police executed 39 Koreans suspected of being “communist”

In light of these events, the claim of John Foster Dulles, writing in the New York Times Magazine, that the ROKA and police had the “highest discipline” and that South Korea was essentially a “healthy society” does not stand up to historical scrutiny.[47] Another popular myth held that the U.S. abandoned South Korea in the late 1940s. American military advisers in reality were all over the country through this period, training Korean soldiers and police, leading counter-insurgency missions. The latter included the forced displacement of villagers that became a basis for the Strategic Hamlet program in South Vietnam. The U.S. provided spotter planes and naval vessels to secure the coasts, even enlisting missionaries to provide information on anti-Rhee guerrillas. ROKA soldiers were “armed to the toenails” with American weapons. They adopted “scorched earth” tactics modeled after Japanese counter-insurgency operations in Manchuria.

While entirely contrary to human rights principles and stated American ideals, the repression in South Korea did have a military benefit, as it deprived Kim Il-Sung’s armies of the support they expected after crossing into South Korea on June 25, 1950.[48] This, combined with modest land reform undertaken by Rhee on the eve of the war, differentiated the war in Korea from that of Vietnam, where resistance in the South was more unified and better able to withstand state repression.

Southern provocations and the origins of the Korean War

There is still a cloud of controversy surrounding the origins of the Korean War. Both Kim Il-Sung and Syngman Rhee had ambitions of unifying the Korean peninsula under their own rule. Prior to July 25, Kim II-Sung undertook a military build-up on the 38th parallel and received clearance for the invasion from Chinese leader Mao Zedong and Soviet premier Joseph Stalin. Yet pitched battles were already being fought across the 38thparallel. There is also speculation that, at 3 a.m. on June 25, South Korean forces under Paek in-Yop may have initiated fighting at Ongjin.[49] Southern provocations, in any case, were considerable.

General Charles Willoughby, MacArthur’s intelligence chief, had opened an extralegal Korean Liaison Office whose mission was to “penetrate North Korean governmental, military and industrial agencies.” Southern youth groups under the pay of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) conducted surveillance and forays into the North in violation of UN provisions. Soviet ambassador Terentii F. Shtykov reported that South Korea had “set up subversive and guerrilla bands in every province in North Korea.”

U.S. police adviser Millard Shaw considered the cross-border operations acts “bordering on terrorism” which “precipitate retaliatory raids … from the North .”[50] The North claimed that in light of these raids that its own actions were carried out in self-defense, and there is some justification behind that reasoning.

On war’s eve, seasoned intelligence analyst Lt. Walter Choinski and the South Korean G-2 chief of staff were curiously transferred and a report by distinguished cross recipient Donald Nichol predicting a North Korean attack 72 hours before was suppressed by Willoughby. This contributed to the “intelligence failure” that rendered the North Korean attack of June 25th a “surprise;” a perception that made the war more politically palatable.[51]

On June 8th, the United States had refused a proposal by Kim Il-Sung to exchange political prisoners and hold elections and form a parliament that would meet in Seoul and unify the country, considering the proposal a propaganda ploy. On the 19th, John Foster Dulles took a trip to the 38th parallel with the blessing of Assistant Defense Secretary Dean Rusk, which stoked North Korean suspicions and hastened the decision to go forward with the invasion.[52]

Soviet leaders only reluctantly sanctioned the North Korean invasion after prodding by Kim, making the North pay for military hardware (unlike the U.S.). Stalin cautioned Kim “if you get kicked in the teeth, I shall not lift a finger. You have to ask Mao [Zedong] for all the help.”[53] Evidence from the Soviet archives suggests that Stalin feared that an American defeat in Korea might trigger a global war. He was prepared to accept U.S. dominance of the peninsula, telling one of his subordinates: “let the United States be our neighbors in the Far East. They will come there but we shall not fight them now. We are not ready to fight.”[54]

Although the CIA had found little evidence that “the USSR was prepared to support North Korea,” the Truman administration deemed the North Korean invasion an act of Russian aggression. Secretary of State Dean Acheson actually greeted the invasion with relief, as it justified massive military appropriations that were essential to carrying out the vision of American pre-eminence outlined in the top-secret National Security Council Report 68 of April 1950. In a press club speech on January 12, 1950, Acheson, a former Wall Street lawyer, had excluded Korea from the American defense perimeter, perhaps to keep the North Koreans off-balance, earning him the opprobrium of Republicans still enraged by the triumph of China’s Maoist revolution. Korea subsequently became a test case to show that the Democrats were willing to stand up to “communist aggression.”[55]

Secretary of State Dean Acheson

Acheson, one of the war’s main architects, was himself an Anglophile with a lifelong admiration of the British Empire. Radical journalist I. F. Stone commented that he represented not the “free American spirit” but something “old, wrinkled, crafty and cruel, which stinks from centuries of corruption.” Showing little empathy or consideration for the Korean people, Acheson said Korea was “not a local situation” but the “spear-point of a drive made by the whole communist control group on the entire power position of the West.” Inaction in the face of invasion, he believed, would damage U.S. credibility, and the international system involving international treaties, the Marshall Plan and NATO, and would cause communists to seize Formosa, Indochina, and finally Japan as well as give strength to domestic isolationists whom he loathed.[56]

While the initial goals of the Truman administration were defensive from its point of view in thwarting the North Korean invasion, they quickly shifted to destroying the North Korean army and humbling the Soviets, and by September 1950, pushing for a unified Korea under Syngman Rhee.

Domestic politics and bipartisan support for the war

President Harry S. Truman wrote in his memoirs that the decision to wage war in Korea was one of the toughest of his presidency and that he felt he could not replicate the mistakes of the generation that had appeased Hitler, referencing the so-called Munich paradigm (the failure of America’s allies to stand up to Hitler after he invaded Czechoslovakia in 1938). This historical analogy dominated policy thinking in the early Cold War. Based on this reading of history, Truman believed he had to act quickly and forcefully to block communist aggression in Korea.

On the other hand, he wanted to avoid a third world war, which seemed quite possible at the time. As the Soviets had successfully developed a nuclear bomb in 1949, this could mean a nuclear war.

U.S. military leaders were concerned as well. Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson and Army Joint Chief of Staff Chairman Omar Bradley worried about committing ground troops to a far-away conflict of limited strategic significance. Even Gen. Douglas MacArthur had told aides in Tokyo that “anyone who engages the U.S. army on the mainland of Asia should have his reason examined.”[57] (Once in the war, however, MacArthur was intent on using all means to achieve victory.).

To sell the war to the public, Truman evoked fears of global communist domination and relied on UN Security Council support to legitimate the U.S.-led “police action” in Korea. The “scare” campaign proved highly effective as 81 percent of Americans initially backed the intervention, according to a Gallup poll taken during the first week of the war.[58] Time Magazine acknowledged that “it was a rare U.S. citizen that could pass a detailed quiz on the little piece of Asiatic peninsula he had just guaranteed with troops, planes and ships.” For most Americans, the threat came from the Soviet Union rather than from North Korea. The magazine quoted Evar Malin, 37, of Sycamore, Illinois: “I’ll tell ya, I think we done the right thing. We had to take some kind of action against the Russians.”[59] The magazine’s editors similarly identified the Russians as the real enemy. “Russia’s latest aggression had united the U.S. — and the U.N. — as nothing else could,” they wrote. “By decision of the U.S. and the U.N., the free world would now try to strike back, deal with the limited crises through which Communism was advancing.”

The Red Scare was at its height in the early 1950s. According to a Gallup poll taken July 30-August 4, 1950, forty percent of Americans advocated placing domestic communists in concentration camps.[60] Historian Mary S. McAuliffe wrote that the fears and frustrations of the Korean War provided a “psychological climate in which the domestic red scare already well rooted began to flourish.”

Truman had personally denounced Joseph McCarthy’s tactics but his hard-line foreign policy rhetoric and initiation of a domestic loyalty program raised the level of public anxiety about communism and buttressed the right-wing crusade.[61] Attacking Truman for the “loss of China” following the 1949 Maoist revolution, McCarthy and Congressional Republicans staunchly supported the Korean War, believing in the need for a “seawall of blood and flesh and steel to hold back the communist hordes.”[62] Disdainful of the decision to withdraw U.S. forces in 1949, the GOP went after “Red” Dean Acheson for alleged communist appeasement. Dwight Eisenhower wrote in his memoir, Mandate for Change, that Acheson’s speech had “encouraged the communists to attack South Korea.”

Senator Styles Bridges, Republican of New Hampshire, spoke for many of his colleagues on June 26, 1950, in affirming the “need to draw the line against communism here and now.” Charles Eaton, top Republican on the House Foreign Affairs Committee said, “We’ve got a rattlesnake by the tail and the sooner we pound its damn head, the better.” Senator William Knowland, a reactionary from California with ties to the China lobby which pushed for an aggressive anticommunist rollback policy, warned that if South Korea falls, “all of Asia is in danger,” an invocation of the domino theory also applied to Vietnam.[63]

Mr. Republican, Robert Taft of Ohio, often deemed an “isolationist,” had felt the Russians were responsible for the war and thus was among the staunch supporters of U.S. intervention. Taft, however, did criticize Truman’s failure to obtain congressional authorization as mandated in the Constitution. He told his Senate colleagues that “if the president has unlimited power to involve us in war, war is more likely [as] history shows that when the people have the opportunity to speak, as a rule the people speak for peace.”[64]

Taft’s view of Constitutional requirements was opposed by liberal historians Henry Steele Commager (of Columbia University) and Arthur Schlesinger Jr., key figures in Americans for Democratic Action (ADA). The two defended a strong executive and argued that the president had every-right to deploy troops on his own authority. Schlesinger, a Harvard university historian and later aide to John F. Kennedy, was the author of the 1949 book, The Vital Center, a blueprint for centrist-liberal domestic policies and aggressive anticommunist foreign policies.

The theologian Reinhold Neibuhr, an ADA co-founder, justified the war as a necessary response to the evils of totalitarianism. Niebuhr’s conservative, pessimistic outlook resonated with practitioners of real-politick such as Hans Morgenthau and George F. Kennan. These utilitarian nationalists promoted a foreign policy guided not by idealism but by strict national and power interests, which was applied in support of the Korean War.[65] Kennan actually expressed his delight that despite being a democracy the U.S. could “stand up in a time of crisis,” though he later questioned the decision to cross the 38th parallel.[66]

Liberal Democrats in Congress almost universally rallied behind Truman’s decision to go to war.

Senators Paul Douglas of Illinois and Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, who had sponsored a bill criminalizing membership in the Communist Party, argued forcefully that Congress should not delay the executive branch’s action by debate. Douglas cited many instances in U.S. history where the President had waged war by executive decree. Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, the 1952 vice presidential nominee, said if the President had “done any less, we would have forfeited the position of leadership of the United States in the free world today.” Abraham Ribicoff of Connecticut brought up the Munich paradigm, asking rhetorically, “What difference is there in the action of North Korea today and the actions which led to the Second World War? Talk about parallels!”[67]

Progressive-minded critics of the Cold War had grown quieter in the wake of Henry A. Wallace’s overwhelming defeat in his bid for the presidency in 1948. Wallace served as the nation’s vice president under Franklin Roosevelt from 1941 to 1945, then as Commerce Secretary in the Truman administration. He was forced to resign the latter position after making a speech at Madison Square Garden in September 1946 in which he warned that Truman’s foreign policies could lead to a third world war.

Two years later, as presidential candidate on the Progressive Party ticket, Wallace advocated for universal health care, racial integration, and a new “people’s century” devoid of war and imperialism. He supported peaceful cooperation with the Russians who he did not consider a military threat.[68] Wallace was smeared during the campaign as pro-communist. Presidential adviser Clark Clifford advised Truman that “every effort must be made to….identify and isolate [Wallace] in the public mind with the communists.”[69]

When the Korean War broke out, the remnants of the Progressive Party objected to the UN Security Council’s call to aid South Korea. Wallace himself, however, supported the UN Security Council’s action and U.S. involvement, stating that when his country goes to war and that war is sanctioned by the UN, he had to support his country and the UN. This position prompted Wallace’s resignation from the Progressive Party which declined thereafter.[70]

Senator Claude Pepper, Democrat of Florida, a onetime Wallace supporter who had criticized the Truman doctrine along with U.S. aid to Greece and Turkey, stressed the prevailing view that China’s involvement in the war (in late November 1950) was “not brought on by American troops crossing the 38th parallel,” but was rather part of “Moscow’s aggressive campaign for conquest of the whole of the Far East,” which the U.S. had to oppose. Democratic Senator Joseph C.O. Mahoney of Wyoming agreed that “the Chinese are the puppets” to their “red masters” in the Kremlin, while Dennis Chavez, the first Democratic Party Hispanic Senator from New Mexico underlined the concept of a Soviet controlled world communism stating: “a communist is a communist whether he is a Russian, a Chinese, an American or a Frenchman.”[71]

This position was strikingly similar to that of the Republican Party. In the November 1950 midterm elections, the GOP picked up 28 seats in the House of Representatives and won 18 contested seats in the Senate. Republican leaders thus felt they had a mandate to aggressively push the rollback doctrine over Truman’s policy of limited war and containment of communism.[72] The Republican platform of 1952 decried the “negative, futile and immoral policy of ‘containment’ which abandons countless human beings to a despotism and godless terrorism.”[73] A real fear of nuclear war nonetheless deterred Republicans and Democrats alike from calling for an invasion of China and Eastern Europe, where communist governments reigned.

Liberals were not entirely or permanently snowed by Truman’s justifications for the war. Many initially supported the war because it signified the successful application of the principle of “collective security” upon which the United Nations is founded. As it became clearer during the war that the U.S. was manipulating the UN to serve its Cold War interests, and that the horrific U.S. bombing of Korea lay outside the boundaries of civilized warfare, criticism of the war became more common, albeit without any recommendation to withdraw.

Vito Marcantonio

Vito Marcantonio of the American Labor Party was the sole member of Congress to disavow U.S. intervention in Korea on the grounds of Korea’s right to self-determination. Calling the Rhee government corrupt and fascistic, he told war supporters that “you can keep on making impassioned pleas for the destruction of communism but I tell you, the issue in China, in Asia, in Korea, and in Vietnam, is the right of these people for self-determination, to a government of their own, to independence and national unity.” Earning the ire of the China lobby, Marcantonio lost his seat in the fall election of 1950.[74]

Potential allies of progressives – labor, minority, and religious groups – generally followed mainstream opinion on the war. With workers benefiting from war-related contracts, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO) supported U.S. intervention in Korea. The CIO executive board called for “complete and unhesitating cooperation of every individual in America.”[75] In the conformist climate of the time, mainstream civil rights groups such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) supported the war.

A Philip Randolph issued a statement on behalf of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters that “Negroes and other minorities and labor have a stake in the victory of the policy of President Truman…. The ruthless and vicious attack of the Russian satellite, North Korea, upon her sister nation is a violent breech of good faith by the Kremlin [and] shows that Russia is bent on world conquest.”[76] These comments attest to the pervasive Cold War mentality underlying broad-scale public support for the Korean War.

The Catholic Church and ascendant Protestant Christian right were major supporters of the Korean War and the Cold War crusade in general, which helped shape Middle American backing of the war. Evangelical preacher Billy Graham called the Truman administration “cowardly” for pursuing a “half-hearted war” rather than following the advice of General Douglas MacArthur and employing the full powers of the American military. Cardinal Francis Spellman, another influential religious leader, visited the troops in Korea, advocated universal military training, and linked U.S. actions in Korea to the will of God.

After General Matthew Ridgeway was quoted in the New York Herald Tribune saying that “our aim is to kill Chinese rather than to capture ground in the current action,” Cardinal Spellman preached that he “dare[d] hope that all at home, inspired by our boys’ heroic giving of themselves for us, may better understand the true meaning of Christmas and more strongly unite to keep God’s peace and the freedom’s he bequeathed to us.” He went on to refer to the “sublime sacrifice of mothers’ sons in emulation of that first Mother’s son who suffered and died,” rendering comparison between the suffering on the cross of Jesus with those sent to Korea to kill the evil, godless communists.[77]

[Continued Part III]

The Author of “The Korean War,” Professor Jeremy Kuzmarov teaches history at the University of Tulsa. He is author of The Myth of the Addicted Army: Vietnam and the Modern War on Drugs (University of Massachusetts Press, 2009) and Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation Building in the American Century (University of Massachusetts Press, 2012). He is active in the Historians Against the War and the Tulsa Peace fellowship, and is a blogger for The Huffington Post.

The original source of the article from United States Foreign Policy: History & Resource Guide

The 21st Century