Marking the 60th anniversary of the inaugural, Belgrade conference of the Non-aligned Movement (NaM) (Aug-Sep 1961), the International Institute for Middle East and Balkans Studies (IFIMES) conducts series of research papers and reports. Hence, the first of them:

Following the famous argument of Prof. Anis H. Bajrektarevic ‘No Asian century without pan-Asian multilateral settings’ which was prolifically published as policy paper and thoroughly debated among practitioners and academia in over 40 countries on all continents for the past 15 years, hereby the author is revisiting and rethinking this very argument, its validity and gravity.

Today Eurasia is the axial continent of mankind, which is home to about 75% of the world’s population (see Map 1), produces 60% of world GDP (see Map 2) and stores three quarters of the world’s energy resources (see Map 3) [Shepard, 2016]. In these open spaces, two giant poles of modern geoeconomics are being formed: European and East Asian, which are tearing the canvas of the familiar geographical concept of “Eurasia” and at the same time providing opportunities for new synthesis through the construction and connection of transcontinental transport arteries.

Map 1: World’s population density (per square kilometer)

Source: WHO, 2019

In the XX century, a united Europe was able to consolidate the power of its members and create the largest bloc that challenged the world hegemon – the United States, and the rapidly growing Asian giants – India and China. However, today the issue of the fact that the world economy is beginning to rely more and more on the East Asian pole of high technologies is being discussed more actively (see Map 4) [Tobny, 2019]. World geopolitics talk about the transformation of the Pacific Ocean into the same centre of business activity as the Mediterranean Sea in ancient times.

Map 2: Global GDP Purchasing Power Parity

Source: International Monetarny Fund World Economic Outlook, 2019

Map 3: World’s natural resources map

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020

Map 4: IMF Projects Economic Growth for Critical Few in 2020

Source: International Monetary Fund,2019

At the end of the XIX century John Hay – US Secretary of State, stated: “The Mediterranean is the ocean of the past, the Atlantic is the ocean of the present, the Pacific is the ocean of the future” [Lehmann&Engammare, 2014]. Statistics show [Akhtar, 2018] that today the Asia – Pacific region (hereinafter APR) has become a powerful world theatre. Ascending Asia encompasses a vast triangle stretching from the Russian Far East and Korea in the northeast to Australia in the south and Pakistan in the west (see Map 5). This triangle contains many of the leading industrialized countries of the modern world – Japan, China, Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, which are characterized by the fastest rates of economic development [Reynolds, 2021]. In the water area of the region a new global reproduction complex is being formed, which today provides more than half of world production and world trade, almost half of the inflow of foreign direct investment (see Map 4).

In the XXI century, it was impossible not to notice the rapid economic growth of Asia, given that the growth rates of each of the national economies of the region exceed those of the Western countries. However, the assertion about the beginning of the Asian century is still vague.

Asia’s economic resurgence and cumulative financial strengths over the last two decades have largely contributed to the global shift of power to Asia [Medcalf, 2018], nevertheless how politically and economically stable the “dominance” of Asia? To answer this question, one need to refer to history of the region and its current geopolitical status-quo.

Map 5: Political map of Eurasia

Source: WorldAtlas, 2021

Source: WorldAtlas, 2021

At the end of the last century and the beginning of this century, Asia flourished because the Pax Americana period after the end of World War II provided a favourable strategic context. But now the twists and turns of US – China relations are raising questions about the future of Asia and the structure of the emerging international order.

For a long time, Asian countries have taken the best of both worlds, building economic relations with China, and maintaining strong ties with the United States and other developed countries. Many Asian states for a long time have considered the United States and other developed countries as their main economic partners [Tran, 2019]. But now they are increasingly taking advantage of the opportunities created by China’s rapid development [Harada, 2020].

Due to the new geopolitical situation, the countries of the East Asia region are concerned [Rsis, 2021] that, being at the intersection of the interests of major powers, they may find themselves between two fires and will be forced to make difficult choices. In this regard, countries understand that the status-quo in Asia must change. But whether the new configuration will further prosper or bring dangerous instability remains to be seen.

It is worth noting that Asian countries view the United States as a power present in the region and having vital interests there. At the same time, China and India are immediate and close reality. Asian countries don’t want to choose between them. And if they face this challenge – Washington will try to contain the growth of China or Beijing will make efforts to create an exclusive sphere of influence in Asia – they will embark on the path of confrontation that will drag on for decades and jeopardize the highly-discussed Asian century.

An important element that can resolve the issue of the status-quo in the region is the fact, that the largest world’s continent must consider creation of the comprehensive pan-Asian institution, as the other major theatres do have in place already for many decades [Kuo, 2018] (i.e., the Organization of American States – OAS (American continent), African Union – AU (Africa), Council of Europe and Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe – OSCE (Europe)) (see Map 6).

Map 6: Atlas of international organizations

Source: Wikimedia Commons Atlas, 2020

The steps taken by the countries of the leading regions of the world to create a single market and a zone of co-prosperity in recent years have given rise to a desire for consolidation among the leaders of Asian countries [Frost, 2008]. Thus, today Asia is a place of concentration of the largest integration groupings, including the Asia – Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), its’ countries are members of large organizations: the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), BRICS, G-20, G-8, E-7. These integration groupings are closely interconnected, widely diversified (Commonwealth of Nations) or specialized (OPEC) (see Map 6). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that in Asia there is still the absence of any pan-Asian security/ multilateral structure, which leaves many issues of cooperation between countries (especially in the field of security and interstate territorial disputes) unresolved [Kaisheng, 2015]. Thus, in Asia the presence of the multilateral regional settings is limited [Bajrektarevic, 2013] to a very few spots in the largest continent, and even then, they are rarely mandated with security issues in their declared scope of work (see Map 6).

Underlining the importance of the creation on multilateral mechanism in Asia, one need to analyse in details the conflicts’ map of the region. The world’s map, which is showing the world’s countries involved in land or border disputes, categorizes the conflicts according to their gravity, from dormant disputes to active conflicts (countries marked in grey have none) (see Map 7), (see Map 29). Thus, Central and Western Africa, Asia and the Middle East emerge as the areas of the world with most active territorial conflicts [Conant, 2014].

Map 7: All world’s ongoing territorial disputes (intensity index)

Source: CIA World Factbook, 2020

The historical background of Asian region shows that Asia has witnessed more territorial disputes, and more armed conflicts over disputed territory, than any other region in the world (see Map 8) [Mancini, 2013]. In 2000, Asia also accounted for almost 40 % of all active territorial disputes worldwide [Fravel, 2014]. Thus, today territorial disputes in Asia remain a serious challenge to peace, stability, and prosperity of the countries. The geopolitical shifts, natural resources, and environmental degradation are a source of concern (see Map 29). The East and South China Seas are flashpoints that could lead to devastating confrontations for the region and beyond.

Map 8: Asia’s Disputed Borders

Source: Business Insider, 2020

Dividing the region to subregional level Asia as a region includes Northern (Northeast) Asia, China & Far East (Eastern Asia), South – Eastern Asia, Western Asia, South Asia, and Central Asia (see Map 9). Among them Western Asia and Central Asia has higher conflict potential, which influence the interstate cooperation.

Map 9.: Subregions of Asia

Source: National Geography, 2018

Source: National Geography, 2018

The subregion of Central Asia is west of China, south of Russia, and north of Afghanistan. The western border of this region runs along the Caspian Sea. It is politically divided into five countries: Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan (see Map 10).

Two post-Soviet Caspian Sea sub-regions – Central Asia and the South Caucasus – have experienced different conflict scenarios. The South Caucasus has been embroiled in protracted, large-scale armed conflicts, while Central Asians have managed to avert a serious armed conflict, remaining largely peaceful despite local, short-term, small-scale clashes, and the existence of factors that may have led – and still may potentially lead – to a serious military conflict (i.e., Armenia – Azerbaijan conflict (The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict[1] [Visual Explainer, 2021]). Conflict map of Central Asia (see Map 11) mainly describes the issue of border settlement is the problem of ethnic enclaves [Indeo, 2020], which is a constant factor of tension in relations between Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan (see Map 29).

Map 10: Central Asia Subregion

Source: Cartarium/Shutterstock, 2019

Map 11: Conflicts of Central Asia region

Source: Jacques Leclerc Research Centre, 2020

To date, of all the currently existing independent states in Central Asia, only Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan have decided to delimit their land borders with neighbouring countries [Zhunisbek, 2021]. The largest number of territorial disputes leading to border armed conflicts arose between Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, which share a common border in the Ferghana Valley, where there is a difficult socio-economic situation (high density and rapid population growth, lack of farmland, lack of water resources), as well as strong positions of supporters of Islamic radicalism.

The conflicts on the borders and border areas of Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in recent years and months allow to characterize the current situation as unstable and tends to worsen (see Map 29).

Western Asia is in the area between Central Asia and Africa, south of Eastern Europe. Most of the region is often referred to as the Middle East, although it geographically excludes the mainland of Egypt (which is culturally considered a Middle Eastern country). West Asia is politically divided into 18 states: Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Cyprus, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Yemen. Iran can also be considered as border state of the subregion. It also includes the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt (see Map 12).

Map 12: Western Asia Map

Source: WorldAtlas, 2019.

The situation in (South-) Western Asia, which covers most of the Near and Middle East, has remained very complex and explosive for half a century. This is largely due to the Palestine – Israeli confrontation in Palestine [BBC, 2021], which escalated in the early twentieth century after the proclamation of the doctrine of creating a “people’s land” for the Jews. The Arab – Israeli confrontation [Boston, 2021], which began in 1948 (the state of Israel was proclaimed), remains unresolved to this day and is a hotbed of armed conflicts in the region (see Map 13).

Map 13: Israel Palestine conflict: A map of the region

Source: Express Politics, 2020

The second hotbed of instability in Southwest Asia for almost a quarter of a century is the forcibly divided Cyprus [Anno, 2015]. The main reasons for the dispute in the region are the instability of the state system based on the principle of ethnic dualism and ethnic confrontation (Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots). Thus, the unresolved political and ethnic disputes not only maintain tensions between NATO members Greece and Turkey, but also complicates the implementation of Cyprus’s initiative to join the European Union.

Unsettled border issues are the reason for the aggravation of the situation in the south of the Arabian Peninsula between Saudi Arabia and Yemen [Martin, 2021]. The border between these states was clearly established only in the southwestern sector (after the military conflict in 1943). In 1993, Saudi Arabia put forward claims for 12 of 20 oil fields located between 17 and 18 parallels, and the negotiations of the border commission have not yielded results so far.

The region’s richness in oil and the lack of agreed borders are the cause of territorial disputes both on land and in the waters of the Persian Gulf: territorial disputes between Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Oman (see Map 14) [Henderson,2008].

Map 14: Natural resources map of Middle East

Source: CIA Factbook, 2016

Islands Abu Musa and Greater and Lesser Tunbs (Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, Strait of Hormuz) – subject of dispute between Iran and the United Arab Emirates [Al-Mazrouei, 2015]. Due to the depth of sea, oil tankers and big ships must pass between Abu Musa and Greater and Lesser Tunbs, which makes these islands some of the most strategic points in the Persian Gulf. The islands are now controlled by Iran, which took control of them in 1971. The conflict between Iran and the UAE periodically flares up and turns into a phase of exchange of harsh statements.

The already dangerous situation in the Persian Gulf region is fuelled by several other regional conflicts: important players in the regional political arena are concerned about the threat of Iranian expansion. The enmity between Iran and Saudi Arabia is based not only on interfaith conflict. Political leadership in the Middle East is at stake.

In addition to those listed above, the Iraqi issue remains a hot spot in the South – West Asia subregion [CRS, 2003]. The overthrown 2003 dictatorial regime of Saddam Hussein and the creation of new government bodies did not save the country from acute internal political conflicts.

The instability of the Caucasus significantly exacerbated the conflict in the region at the beginning of the 21st century: in August 2008, the situation in the region worsened sharply, which was associated with an attempt by Georgia to regain South Ossetia by military means [Lehmkuhl, 2017]. Russia’s intervention in this conflict led to the proclamation of the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The conflict remains unresolved to this day.

Ethno-religious conflicts and the struggle of the Kurds for their statehood, which lasted throughout the entire twentieth century, are important centres of instability in the region [Khalifa&Bonsey, 2013]. The Kurds (according to estimates, at least 20 million people) are settled compactly in mountainous areas at the junction of state borders in the south-eastern part of Turkey (about 10 million people), north-western Iran (5.3 million), northern Iraq (3.0 million) and Syria (1.3 million), more than 0.5 million Kurds live in other countries, in Armenia (see Map 15).

Map 15: Where are the Kurds

Source: The Kurdish Project, 2018

In 1992, the Kurds proclaimed their own state on part of the territory of Iraq, the government of which was not recognized by Iraq, which offered them the preservation of their autonomy status. The “temperature” of the centres of separatism of the Islamic regional type, the greatest contribution to the formation of which was made by ethno-confessional and geopolitical factors, as well as the factor of natural boundaries, today remains relatively high. One of the bloodiest separatist conflicts, as noted above, is the Kurdish one. Since its inception, the number of its victims has exceeded 40 thousand people.

The conflict potential of the region is aggravated by the numerous emigrations of Kurds to Western Europe (Germany, France) and the United States, whose radical groups often resort to terrorist acts. Such approaches and fierce military operations complicate the overall political climate in such a volatile region (see Map 29).

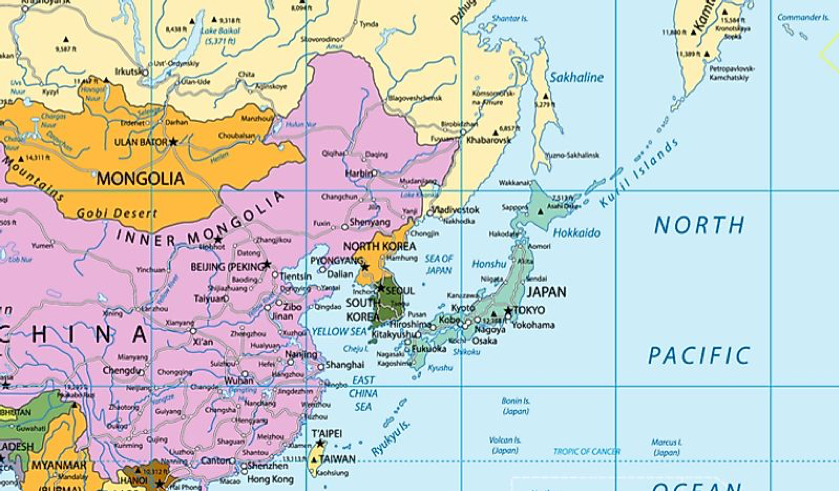

Northern and Eastern Asia is one of the world’s most dynamic areas in terms of economic growth and significance for global trade. While China attracts most attention, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are all strong economies. Add Russia and the US in the mix and the importance of Northeast Asia cannot be overstated.

Northern Asia includes the bulk of Siberia and the North – Eastern edges of the continent and comprises Siberia and Russian Far East, which is in the Asian part of Russia and Mongolia (see Map 16).

Map 16: East Asia

Source: WorldAtlas, 2019

In the Far East and North Asia, destabilizing factors remain the Russian – Japanese territorial dispute over the Kuril Islands (Northern Territory) [Kaczynski, 2020], the Korean – Japanese territorial dispute over the Dokdo Islands (Takeshima) (Liancourt Rocks dispute) [Genova, 2018] and the territorial dispute over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyutai) between Japan and China [SCMP, 2019].

Analysing Russia – Japanese territorial dispute ovel Kuril Islands [Gorenburg, 2012], it can be emphasized that the official position of Japan is that the Kuril Islands were never part of Russia and therefore these islands belong to Japan but are currently illegally occupied by Russia (see Map 17). A peace treaty has not yet been signed due to Japan’s remaining claims to the islands of Kunashir and Iturup. Russia sees no guarantees of the end of the dispute, even after the “theoretically conceivable” transfer of the four disputed islands to the Japanese side.

Map 17: The Kuril Islands

Source: Deutsche Welle analytics, 2016

Japan – South Korea territorial dispute over Liancourt Rocks remains unresolved [Jennings,2017] (since 1965 – the parties concluded a Basic Agreement on Relations) and mainly stems from a controversial interpretation of the fact – whether Japan’s renunciation of sovereignty over its colonies also applies to the Liancourt Islands. Due to this fact Japan recalls its claims and makes attempts to exercise its jurisdiction in the area.

East Asia (China & Far East), one of the subregions of Asia, is including the continental part of the Russian Far East region of Siberia, the East Asian islands, Korea, and eastern and north-eastern China. It is located east of Central Asia, with its eastern border running along the East China Sea. East Asia is politically divided into eight countries and regions: China, North Korea, South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau (see Map 16).

These two regions are characterised by “strategic diversity” where several unresolved territorial disputes threaten to undermine the very source of regional prosperity: maritime trade.

Of all the disputed territories in the APR, a striking example of the high potential of a formally latent territorial dispute in NEA is the conflict over the Senkaku – Diaoyu Islands[2] [European Parliament,2021], in which Japan and China, the two largest economies and two leading foreign policy players in Northern and East Asia (NEA), are parties to the conflict (see Map 18). This conflict illustrates the essence of modern territorial disputes in the region and the essential information component of such processes.

Map 18.: Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands Dispute

Source: Chinese Defense Ministry, EIA, Yonhap, 2015

Currently, territorial disputes over the right to own the above-mentioned region are not resolved. Both China and Japan periodically engage in military provocations.

The further development of the situation around the Senkaku – Diaoyu Islands is likely to take the form of an ongoing foreign policy conflict of moderate intensity, including the alleged periodic escalation-de-escalation. Thus, the consideration of the situation around the Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands makes it clear that this territorial conflict in modern conditions is supported mainly by information actions of its participants. A similar scenario development is typical for many other territorial contradictions in the APR today.

However, other, equally intractable, disputes cannot be neglected. Among these cases are disputes between Japan and Korea over Dokdo/Takeshima Island[3] and the Kuril Islands[4] that are held by Russia but claimed by Japan (See Map 17). Further regional conflicts involve Korean Peninsula[5] disputes [Visual Explainer,2013], disputed fishing areas that frequently witness clashes between fishing boats and respective law enforcement agencies. No less important conflict areas of the region are Korean Peninsula and Chinese territories [Krishnankutty,2020] (namely China – Taiwan[6] [Maizland,2021], the issue of Inner Mongolia[7] [Roney,2013] the issue of Tibet (Tibet Autonomous Region)[8] [Shetty, 2017] and the issue of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region) [Fuller&Starr,2003] (see Map 19).

None of the above-mentioned disputes are likely to be resolved in the foreseeable future. The worst-case scenario is that they continue to plague Japan’s bilateral relations with China, South Korea, and Russia, isolating Japan in the region, and perhaps even resulting in militarized conflict. Though such conflict is unlikely in the disputes with Russia and South Korea, it remains a possibility in the dispute with China.

The recent flare-ups in all three disputes have served to harden domestic opinion on all sides, preventing the states from explicit compromises (see Map 29). But the Northern and Eastern Asia territorial disputes underline an important fact: as the disputes faded from view, public opinion softened slightly, and bilateral trade and other exchanges developed. If the states involved can recognise and pursue their long-term interests, the disputes could be shelved. Over time, if shelving agreements pertained and future flare-ups were avoided, an environment may even develop whereby both sides could reach a compromise agreement. This is perhaps the most optimistic scenario, and it requires a suppression of nationalism and revisionism that may well be impossible. Still, the alternative is a bleak future for not only the disputes, but also for Northeast Asia as a whole.

Map 19: the PRC: Administrative Divisions & Territorial Disputes

Source: South China Morning Post, Infographics, 2019

Southeast Asian subregion is located north of Australia, south of East Asia, west of the Pacific Ocean, and east of the Bay of Bengal. It encompasses several island and archipelago nations that stretch between the northern and southern hemispheres, making it the only Asian region located on both sides of the equator. Southeast Asia is politically divided into 12 countries and territories: Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, East Timor, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam (see Map 20).

In Southeast Asia (hereinafter SEA), compared to other regions, the numbers of unresolved territorial disputes are still considered small [Jenne, 2017], and SEA is considered a relatively safe region with no violence going on due to the unresolved territorial disputes as compared to the Africa region (where the conflicts has involved 9 million people causing them to be refugees and internally displaced people (hereinafter IDP) where hundreds and thousands of people were slaughtered).

Map 20: Southeast Asia

Source: WorldAtlas, 2019

The territorial disputes in SEA consist of the following disputes: the Philippines’ Sabah Claim (The North Borneo)[9], the Ligitan and Sipidan dispute[10][Victoria,2019], the Pedra Branca dispute[11] [Jumrah, 2021] and the South China Sea Conflict Zone also known as the Spratly Islands disputes[12] [Moss,2016] (see Map 21), (see Map 29).

Map 21: China Sea Territory Disputes

Source: Money Morning staff research, NPR, 2021

The country of East Timor, also known as Timor-Leste, which gained independence from Indonesia in 2002, only in 2018 has signed (with Australia) a historic treaty on a permanent maritime border in the Timor Sea – settling the dispute over Timor Gap. The deal ended a decade-long dispute between the neighbours over rights to the sea’s rich oil and gas reserves.

The international border between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, which divides the island of New Guinea in half, represents another hot spot in the region [Cooke,1984]. Tensions between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea grew, as the ongoing West Papuan conflict[13] destabilised the border region, causing flows of refugees and cross-border incursions by Indonesia’s military. Ongoing Papua conflict up to date preserves dangers and high level of violence in the region. Land dispute in which 21 people died (last update as for April 2021 [Fardah,2021]) is the latest brutal conflict exacerbated by high-powered weapons, weak governance, and erosion of traditional mores.

The territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea are considered some of the most complex conflicts in the region if not worldwide [Sakomoto,2021]. The disputed areas are abundant in natural resources such as gas and oil and carry strategic importance, as roughly half of the world’s commercial shipping passes through them. These disputes played an important role not only in the relations among the claimants but also in the foreign policies of countries such as Japan and the United States. The disputes involve overlapping maritime, territorial, and fishing rights and claims by China, Taiwan, Brunei, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia (see Map 21).

However, despite the fact, that territorial disputes in SEA are related to the vagueness of colonial titles and are usually of an acute political (geopolitical) nature, they affect the interests of third States, including superpowers (namely the USA, China, India); involve the analysis of not only territorial titles, but also claims to self-determination; provoke constant tension and are fraught with armed conflicts. Their judicial resolution is usually unlikely, and the use of conciliation mechanisms is preferable.

Despite this, there is little doubt [Avis, 2020] that the conflicts in the South China Sea will dominate the region’s security agenda for years, if not decades, to come. In this case, the ASEAN claimant states have decidedly stuck to their unwritten agreement that some form of settlement needs to be reached with China before any attempt is made to resolve overlapping claims amongst themselves. Thus, the intra-ASEAN disputes in the South China Sea will most likely remain dormant for a considerable time to come [Tønnesson, 2002].

South Asia is Asia’s largest sub-region. It comprises the sub-Himalayan SAARC countries, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (see Map 22). The area is often referred to geologically, as the Indian Subcontinent and appears to be the area with the highest conflict intensity index in the region (see Map 23), (see Map 29).

Map 22: Southern Asia

Source: WorldAtlas, 2019

[The 2nd portion of this long scholarly paper will be published soon.]

By Dr Maria Smotrytska. She is senior research fellow at the International Institute IFIMES, Department for Strategic Studies on Asia (DeSSA), a sinologist specialized in the investment policy of China; Asian affairs; BRI-related initiatives; Sino – European ties, and the like. She holds PhD in International politics for the Central China Normal University (Wuhan, PR China).

Published by IFIMES

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.

References:

- Acharya, Higgott, and Ravenhill, (2016), “Made in America? Agency and Power in Asian Regionalism,” Journal of East Asian Studies, 375.

- Akhtar S., (May,2018), As the Asia-Pacific continues to power the global economy, we must ensure that growth is sustainable, “South China Morning Post” news portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 05 July 2021).

- Al-Mazrouei N.S., (2015), Disputed Islands between UAE and Iran: Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb in the Strait of Hormuz, Gulf Research Centre Cambridge, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Anno C., (2015), The unresolved Cyprus problem, “Le Petit Juriste” media portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- ANU, (1987), Mr Bill Hayden (Minister for Foreign Affairs in the Hawke Government) at the North Pacific Security and Arms Control Conference, Australian National University Archive, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Anwar R., (1988), Asia Pacific Region: Impact Of Gorbachev’s Peace Initiatives, Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- APEC, (2021), History, APEC official website, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Avis W., (2020), Border Disputes and Micro-Conflicts in South and Southeast Asia, GSDRC Research, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Ayres A., (2020), The China-India Border Dispute: What to Know, Council of Foreigner Relation, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Ayson R., (2009), The Six-Party Talks Process: Towards an Asian Concert? in Huisken ed., The Architecture of Security in the Asia-Pacific, p. 64.

- Bajrektarevic A.H., (2013), Is Today’s Europe Tomorrow’s Asia?, Geopolitical Monitor media portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Bajrektarevic A.,H., (2015), No Asian Century without A pan-Asian Institution, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Banerji A.,(2021), India Must Settle the Teesta River Dispute With Bangladesh for Lasting Gains, “The Diplomat” online magazine, URL: , (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- BBC, (Jun.2021), Israel-Gaza violence: The conflict explained, BBC News portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Bisley N., (2015), “China’s Rise and the Making of East Asia’s Security Architecture,” Journal of Contemporary China, p. 22.

- Bhonsale M.,(2018), Understanding Sino-Indian border issues: An analysis of incidents reported in the Indian media, Observer Research Foundation, URL: hyperlink , (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Boston, (May 2021), History of the Israel-Palestinian Conflict and What’s Behind the Latest Clashes, NBC Boston news platform, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Cheng Y., (2014), “Yaxin Fenghui: Fanya Xiezuo Goujian Yazhou Anquan Jizhi [CICA Summit: Pan-Asian Collaboration and Construction of Asian Security Regimes],” China Social Sciences Today, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Conant E., (2014), 6 of the World’s Most Worrisome Disputed Territories, The National Geographic, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 21 July 2021).

- Cooke K., (1984), Indonesia, Papau New Guinea: a big divide, “The Christian Science Monitor”, URL: , (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- CRS, (2003), Iraq War: Background and Issues Overview, CRS Report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- CRS, (2019), The Asia Reassurance Initiative Act (ARIA) of 2018, CRS Report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- D’Ambrogio E., (2018), Kashmir: 70 years of disputes, European Parliamentary Research Service, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Dabas M.,(2016), Everything You Need To Know About The Dispute Over Sir Creek Between India And Pakistan, The Indiatimes Frontlines online journal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Department of Defense of the USA, (2015), Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy, Department of Defense of the USA official Report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Drishti, (2019), Indo-Nepal Territorial Dispute, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- European Parliament, (2021), Sino-Japanese controversy over the Senkaku/Diaoyu/Diaoyutai Islands, European Parliamentary Research Service Briefing Report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Evans G.J., (1995), Our Shared Asia Pacific Future (speech), URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Evans G.J. and Dibb P., (1994), Australian paper on practical proposals for security cooperation in the Asia Pacific region, Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre.; Australia. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Fardah E., (2021), Armed criminals torch homes of Papua tribal chief and teachers, “ANTARA” news agency, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Fravel T., (2014), Territorial and Maritime Boundary Disputes in Asia, Oxford University Press Center, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Friedrichs J., (2012), “East Asian Regional Security,” Asian Survey, Vol. 52, No. 4 July/August, p. 754.

- Frost F., (Oct.2008), ASEAN s regional cooperation and multilateral relations: recent developments and Australia s interests, Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section, Parliament of Australia Report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Fuller G.E. and Starr S.F., (2003), The Xinjiang Problem, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Genova A., (2018), Two nations disputed these small islands for 300 years, The National Geographic, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 01 August 2021).

- Gilani I.,(2020), India’s border dispute with neighbors, “Anadolu Agency” research, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Goh E., (2008), “Hierarchy and the Role of the United States in the East Asian Security Order,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, 353–356.

- Gorenburg D., (2012), The Southern Kuril Islands Dispute, PONARS Eurasia Analysis, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 01 August 2021).

- Harada I., (2020), ASEAN becomes China’s top trade partner as supply chain evolves, Nikkei Asia Reports, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 25 July 2021).

- Haruko W., (2020), The “Indo-Pacific” Concept Geographical Adjustments And Their Implications, The RSIS Working Paper series, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Hague Permanent Court of Arbitration, (2014), In The Matter Of The Bay Of Bengal Maritime Boundary Arbitration Between The People’s Republic Of Bangladesh And The Republic Of India, Hague Permanent Court of Arbitration report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Henderson S., (2008), The Persian Gulf’s ‘Occupied Territory’: The Three-Island Dispute, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Indeo F., (2020), Territorial enclaves in Central Asia, a source of regional instability, NATO Defense College Foundation Reports, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- IST, (2020), Nepal brings out new map marking 3 disputed areas bordering Uttarakhand in its territory, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Jenne N., (2017), Managing Territorial Disputes in Southeast Asia: Is There more than the South China Sea?, SAGE Journals, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Jennings K., (2017), Why the Liancourt Rocks Are Some of the Most Disputed Islands in the World, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 01 August 2021).

- Jilani J., (2019), The Latest Kashmir Conflict Explained, A USIP Fact Sheet, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Jumrah W., (2021), Singapore’s Land Reclamation on Pedra Branca: Implications for Malaysia, “The Diplomat” online magazine, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Kaczynski V.M., (2020), The Kuril Islands Dispute Between Russia and Japan: Perspectives of Three Ocean Powers, Warsaw School of Economics Russian Analytical Digest, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 01 August 2021).

- Kaisheng L., (2015), Future Security Architecture in Asia: Concert of Regimes and the Role of Sino-American Interactions, China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies, Vol. 1, No. 4, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Kapoor C., (2020), Undemarcated boundaries lead India, China border clashes, “Anadolu Agency” research, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Khalifa D. and Bonsey N., (2013), Syria’s Kurds: A Struggle Within a Struggle, “International Crisis Group” media portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Kobayashi S., Baobo J. and Sano J., (1999), “Three Reforms” in China: Progress and Outlook, Sakura Institute of Research, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Kol’tyukov A. A., (2008), Vliyaniye Shankhayskoy organizatsiya sotrudnichestva na razvitiye i bezopasnost’ Tsentral’no-Aziatskogo regiona, Shankhayskaya organizatsiya sotrudnichestva: k novym rubezham razvitiya: Materialy krugl. stola. – M.: In-t Dal’n. Vost. RAN, p. 257-258. (In Russ.).

- Kraft H.J.S., (1993), Philippine-U.S. Security Relations In The Post-Bases Era, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Krishnankutty P., (2020), Not just India, Tibet – China has 17 territorial disputes with its neighbours, on land & sea, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Kuo M.A., (Jun.2018), Regional Security Architectures: Comparing Asia and Europe, “The Diplomat” online magazine, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Larson A., (2018), Afghanistan, “Conciliation Resources” Journal, Issue 27, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Lehmann J.-P. and Engammare V., (Feb.2014), Beyond Economic Integration: European Lessons for Asia Pacific?, “The Globalist” media platform, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 05 July 2021).

- Lehmkuhl D., (2017), Stability and instability in the Caucasus: social cohesion, “Open Access Government” news portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Long D., (2020), India-China border clash explained, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Maizland L., (2021), Why China-Taiwan Relations Are So Tense, Council of Foreigner Relation, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Majumdar M.M., (2000), Canada And Asia Pacific: New Dimensions, SAGE Publications, Inc., URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Mancini F., (2013), Uncertain Borders: Territorial Disputes In Asia, ISPI Reports, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Mapbox, (2021), A World of Disputed Territories, Mapbox Infographics, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 12 August 2021).

- Martin M., (2021), Understanding the Conflicts Leading to Saudi Attacks, Hong Kong by PIMCO Asia Limited reports, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- McDevitt M.A. and Lea C.K., (2013), Japan’s Territorial Disputes, CNA Maritime Asia Project: Workshop Three, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 01 August 2021).

- Medcalf R., (Jan.2018), Reimagining Asia: From Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific, The ASAN Forum Reports, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 23 July, 2021).

- Meyer P.F., (1992), Gorbachev and Post-Gorbachev Policy toward the Korean Peninsula: The Impact of Changing Russian Perceptions, University of California Press, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, (2013), Xi Jinping Starts China-US Presidential Meeting with U.S. President Barack Obama, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC official website, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, (2021), A New Foreign Policy Strategy: “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan official website, URL: hyperllink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Ministry Of Foreign Affairs, Japan (1989), Diplomatic Bluebook.1989. Japan’s Diplomatic Activities, Ministry Of Foreign Affairs, Japan report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Modi N., (2020), INFOGRAPHICS: India’s border dispute with neighbours, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Moss J., (2016), Driving commercial and political engagement between Asia, the Middle East and Europe, Asia House Research Centre, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Nair P., (2009), The Siachen War: Twenty-Five Years On, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 44, No. 11 (Mar. 14 – 20, 2009), pp. 35-40.

- Oresman M., (2005), The Shanghai Cooperation Summit: Where Do We Go From Here?, China-Eurasia Forum Quarterly, Special Edition: The SCO at One, p.17.

- Pejsova E., (2014), East Asia’s Security Architecture – Track Two, European Union Institute for Security Studies, Alert No. 18, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- PTI, (2017), Barahoti a disputed area, no clear demarcation which part belongs to China or India: Uttarakhand CM, “The Indian Express” news portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Ramachandran S., (2021), Expanding and Escalating the China-Bhutan Territorial Dispute, “The Jamestown Foundation Global Research & Analysis”, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Ramirez D., (2020), COVID-19: Global trade and supply chains after the pandemic, IISS Reports, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Reynolds O., (Feb.,2021), The World’s Fastest Growing Economies, Focus Economic Research, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 24 July 2021).

- Roney T., (2013), Opposition in Inner Mongolia, “The Diplomat” online magazine, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Rosand E., Fink N.C., and Ipe J., (2009), Countering Terrorism in South Asia: Strengthening Multilateral Engagement, Center for Global Counterterrorism Cooperation, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Rsis J.N, (2021), Can ASEAN offer a way out of the US–China choice?, East Asia Forum Brief study, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 25 July 2021).

- Runde D., F., (2018), The BUILD Act Has Passed: What’s Next?, CSIS Reports, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Sakomoto S., (2021), The Global South China Sea Issue, “The Diplomat” online magazine, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- SCMP, (2019), Explainer | Diaoyu/Senkaku islands dispute, SCMP Research Center, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 01 August 2021).

- Shepard W., (Oct.2016), Eurasia: The World’s Largest Market Emerges, “The Forbes” magazine, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 20 June 2021).

- Shetty S.S., (2017), What Is The Conflict Between Tibet & China? Know About It, “The Logical Indian” media platform, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- SIPRI, (2021), World military spending rises to almost $2 trillion in 2020, the Stockholm Peace Research Institute Press Release, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Smotrytska M., (2020), Belt and Road in the Central and Eastern EU and non-EU Europe: Obstacles, Sentiments, Challenges, Energy Observer think-tank, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Smotrytska M., (2021), IFIMES Analysis of China’s “Belt and Road” Initiative: Genesis and Development, International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies, Department for Strategic Studies on Asia (IFIMES), URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Solomon R.H. and Drennan W.M, (2001), The United States And Asia In 2000 Forward To The Past?, University of California Press, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Tian N., Kuimova A., da Silva D.L., Wezeman P.D. and Wezeman S.T., (2020), Trends In World Military Expenditure, 2019, the Stockholm Peace Research Institute Research, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Tonby O., (Jul.2019), The forces shaping Asia’s future, McKinsey&Company Research, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 20 June 2021).

- Tønnesson S., (2002), Why are the Disputes in the South China Sea So Intractable? A Historical Approach, Asian Journal of Social Science, Vol. 30, No. 3, SPECIAL FOCUS: Research on Southeast Asia in the Nordic Countries (2002), pp. 570-601

- Tran K.M., (Jun.2019), U.S.–Southeast Asia Trade Relations in an Age of Disruption, CSIS Report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 23 July 2021).

- USIP, (2021), The Current Situation in Afghanistan, A USIP Fact Sheet, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Victoria A., (2019), Dispute International Between Indonesia and Malaysia Seize on Sipadan and Lingitan Island, International Journal of Law Reconstruction 3(1), URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Visual Explainer, (2013), The Korean Peninsula: Flirting with Conflict, “International Crisis Group” media portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 07 August 2021).

- Visual Explainer, (2021), The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: A Visual Explainer, “International Crisis Group” media portal, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 09 August 2021).

- Weitz R., (2014), The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Fading Star?, The ASAN Forum report, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).

- Zhunisbek A., (2021), Current State of Border Issues in Central Asia, Eurasian Research Institute, URL: hyperlink, (accessed: 26 July 2021).