It may be that we have inched back from the precipice of war in Syria, if for no other reason than a hefty gust of sheer luck. Russia’s intervention and neutralisation of the escalating tension between the US and the Assad regime has saved Obama from near certain defeat in Congress, with the UK government already rebuked and the Security Council never a viable option. The project was going soak up significant political capital for Obama and the well is nearly already dry. This political lacuna, or hopefully ongoing calm, presents a useful moment for reflection on the way war is propagated.

There are, of course, plenty of obvious and practical reasons to oppose a military intervention into Syria. The first is that we know so very little about the chemical weapons attacks of late August: how they transpired, who was responsible, even how many people died. The UN has only made limited findings and declined to apportion blame. It appears to be very difficult to work out who was responsible – a task that isunlikely to get easier. It is reasonable to think that even if Assad’s regime was responsible, it may be that both sides have chemical weapon capabilities.

We know about such capabilities partly because Britain kept the receipts. It is true: such an allegation is probably more spin than substance – the origins of the weapons have not been identified and the chemicals exported could be used for other purposes. But the brazen hypocrisy of the West in claiming to uphold principles it happily profits from violating never ceases to amaze.

Moreover, for even the more pragmatic amongst us, the lesser of two evils here is not clear cut. A direct attack on the Assad regime would necessarily result in a military and political advantage to oppositional forces. The beneficiaries of such a move include some nefarious characters, with little regard for human life or dignity.

Indeed the only certainty that arising from a military intervention into Syria is that nothing would be certain. A ‘limited and tailored’ intervention is a thinly disguised Pandora ’s Box. No fly zones can easily become regime change, the distinction marked by grainy phone camera footage of the extrajudicial killing of Muammar Gaddafi. Libya is the perfectly instructive example, yet it has also been conveniently banished from the public consciousness. Two years after the imposition of a no fly zone in very similar circumstances, enforced militarily by the US and NATO, the country remains an economic, political and social disaster.

And yet this ahistorical approach to international affairs persists, which sees the conflict in binary terms of intervention and abstention, certain death and saving lives. It is so typical, so repetitive; the serious lack of imagination matched only by the gravity of the lethal project being proposed. The hawks circle, their hopes are still soaring well above the vigilance of doves. ‘At some point,’ they claim, ‘pacifism becomes part of the machinery of death, and isolationism becomes a form of genocide.’ Quite literally then, war is peace.

Yet despite these familiar refrains, the prospect of a war in Syria is in fact remarkably different to those of recent memory. The factual and rhetorical justification already feels far more flimsy, the political classes in a number of countries remain fractured on the question generally and the vast majority of everyday people are steadfastly opposed to intervention. This is undoubtedly a step forward.

What is also laid bare in breathtaking terms by the advocates for war is how little regard they have for basic liberal democratic values. The US treats international law with disdain: it is a set of rules that applies to everyone but never to itself. Cheerleaders for the diplomatic strategy that Obama appears to have stumbled into almost by accident seem oblivious to the criminality of such conduct. Article 2 of the UN Charter prohibits the ‘threat or use of force’ – threat, not just use – for all members, not just when such conduct is carried out by suspicious Middle Eastern dictators. The criminality of Obama’s diplomatic genius is barely noted.

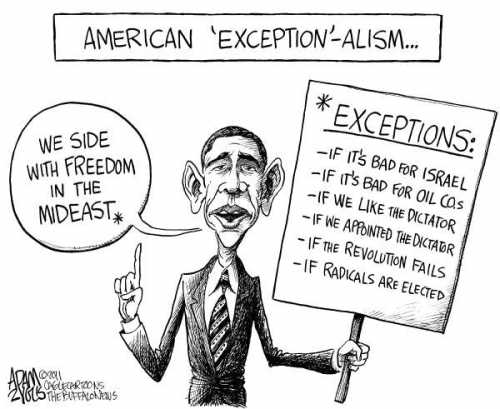

The irony of such attitudes to international law intensifies in respect of chemical weapons. The situation in Syria, as Professor Chomsky hasidentified, is a perfect moment to call for a ban on all chemical weapons in the Middle East (let alone elsewhere). The chemical weapons convention, surely the starting point for any reasonable discussion on such an issue, remains persistently unratified by not only Syria, but crucially also Israel. So chemical weapons are not okay, unless it is our man in the Middle East who has them.

So the biggest barrier to ridding the Middle East of chemical weapons is not Syria or Russia, or even technically Israel, it is actually the US. That is not a rhetorical flourish, it is literally the outcome of a resolution proposed by Syria in 2003 when it was a non-permanent member of the Security Council, but ultimately abandoned at the threat of the US exercising its veto. American exceptionalism continues to justify even more American exceptionalism.

Anne Orford, writing on Libya, observed that ‘the bombing of Libya in the name of revolution may be legal, but the international law that authorises such action has surely lost its claim to be universal.’ In respect to Syria, we see this legacy gaining momentum. International law appears to have become something to be enforced but not abided by. This may seem grandiose, but the truth is hard to deny: one of the greatest menaces in the world today remains the US Government. The aspiration of peace, good governance and respect for human rights are regularly jeopardised by this ultimate rogue state.

Elizabeth O’Shea is a lawyer in Melbourne, Australia. – This article was originally published at Counterpunch