CONFRONTATION BETWEEN MILITARY BLOCS: The Eurasian “Triple Alliance”

|

Despite areas of difference and rivalries between Moscow and Tehran, ties between the two countries, based on common interests, have developed significantly. Both Russia and Iran are both major energy exporters, they have deeply seated interests in the South Caucasus. They are both firmly opposed to NATO’s missile shield, with a view to preventing the U.S. and E.U. from controlling the energy corridors around the Caspian Sea Basin. Moscow and Tehran’s bilateral ties are also part of a broader and overlapping alliance involving Armenia, Tajikistan, Belarus, Syria, and Venezuela. Yet, above all things, both republics are also two of Washington’s main geo-strategic targets. The Eurasian Triple Alliance: The Strategic Importance of Iran for Russia and China China, the Russian Federation, and Iran are widely considered to be allies and partners. Together the Russian Federation, the People’s Republic of China, and the Islamic Republic of Iran form a strategic barrier directed against U.S. expansionism. The three countries form a “triple alliance,” which constitutes the core of a Eurasian coalition directed against U.S. encroachment into Eurasia and its quest for global hegemony. While China confronts U.S. encroachment in East Asia and the Pacific, Iran and Russia respectively confront the U.S. led coalition in Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. All three countries are threatened in Central Asia and are wary of the U.S. and NATO military presence in Afghanistan. Iran can be characterized as a geo-strategic pivot. The geo-political equation in Eurasia very much hinges on the structure of Iran’s political alliances. Were Iran to become an ally of the United States, this would seriously hamper or even destabilize Russia and China. This also pertains to Iran’s ethno-cultural, linguistic, economic, religious, and geo-political links to the Caucasus and Central Asia. Moreover, were the structure of political alliances to shift in favor of the U.S., Iran could also become the greatest conduit for U.S. influence and expansion in the Caucasus and Central Asia. This has to do with the fact that Iran is the gateway to Russia’s soft southern underbelly (or “Near Abroad”) in the Caucasus and Central Asia. In such a scenario, Russia as an energy corridor would be weakened as Washington would “unlock” Iran’s potential as a primary energy corridor for the Caspian Sea Basin, implying de facto U.S. geopolitical control over Iranian pipeline routes. In this regard, part of Russia’s success as an energy transit route has been due to U.S. efforts to weaken Iran by preventing energy from transiting through Iranian territory. If Iran were to “change camps” and enter the U.S. sphere of influence, China’s economy and national security would also be held hostage on two counts. Chinese energy security would be threatened directly because Iranian energy reserves would no longer be secure and would be subject to U.S. geo-political interests. Additionally, Central Asia could also re-orient its orbit should Washington open a direct and enforced conduit from the open seas via Iran. Thus, both Russia and China want a strategic alliance with Iran as a means of screening them from the geo-political encroachment of the United States. “Fortress Eurasia” would be left exposed without Iran. This is why neither Russia nor China could ever accept a war against Iran. Should Washington transform Iran into a client then Russia and China would be under threat.

There is a major misreading of past Russian and Chinese support of U.N. sanctions against Iran. Even though Beijing and Moscow allowed U.N. Security Council sanctions to be passed against their Iranian ally, they did it for strategic reasons, namely with a view to keeping Iran out of Washington’s orbit. In reality, the United States would much rather co-opt Tehran as a satellite or junior partner than take the unnecessary risk and gamble of an all-out war with the Iranians. What Russian and Chinese support for past sanctions did was to allow for the development of a wider rift between Tehran and Washington. In this regard, realpolitik is at work. As American-Iranian tensions broaden, Iranian relations with Russia and China become closer and Iran becomes more and more entrenched in its relationship with Moscow and Beijing. Russia and China, however, would never support crippling sanctions or any form of economic embargo that would threaten Iranian national security. This is why both China and Russia have refused to be coerced by Washington into joining its new 2012 unilateral sanctions. The Russians have also warned the European Union to stop being Washington’s pawns, because they are hurting themselves by playing along with the schemes of the United States. In this regard Russia commented on the impractical and virtually unworkable E.U. plans for an oil embargo against Iran. Tehran has also made similar warnings and has dismissed the E.U. oil embargo as a psychological tactic that is bound to fail.

Russo-Iranian Security Cooperation and Strategic Coordination In August 2011, the head of the Supreme National Security Council of Iran, Secretary-General Saaed (Said) Jalili, and the head of the National Security Council of the Russian Federation, Secretary Nikolai Platonovich Patrushev met in Tehran to discuss the Iranian nuclear energy program as well as bilateral cooperation. Russia wanted to help Iran rebuff the new wave of accusations by Washington directed against Iran. Soon after Patrushev and his Russian team arrived in Tehran, the Iranian Foreign Minister, Ali Akbar Salehi, flew to Moscow. Both Jalili and Patrushev met again in September 2011, but this time in Russia. Jalili went to Moscow first and then crossed the Urals to the Russian city of Yekaterinburg. The Iran-Russia Yekaterinburg meeting took place on the sidelines of an international security summit. Moreover, at this venue, it was announced that the highest bodies of national security in Moscow and Tehran would henceforth coordinate by holding regular meetings. A protocol between the two countries was was signed at Yekaterinburg. During this important gathering, both Jalili and Patrushev held meetings with their Chinese counterpart, Meng Jianzhu. As a result of these meetings, a similar process of bilateral consultation between the national security councils of Iran and China was established. Moreover, the parties also discussed the formation of a supranational security council within the Shanghai Cooperation Council to confront threats directed against Beijing, Tehran, Moscow and their Eurasian allies. Also in September 2011, Dmitry Rogozin, the Russian envoy to NATO, announced that he would be visiting Tehran in the near future to discuss the NATO missile shield project, which both the Moscow and Tehran oppose. Reports claiming that Russia, Iran, and China were planning on creating a joint missile shield started to surface. Rogozin, who had warned in August 2011 that Syria and Yemen would be attacked as “stepping stones” in the broader confrontation directed against Tehran, responded by publicly refuting the reports pertaining to the establishment of a joint Sino-Russo-Iranian missile shield project. The following month, in October 2011, Russia and Iran announced that they would be expanding ties in all fields. Soon after, in November 2011, Iran and Russia signed a strategic cooperation and partnership agreement between their highest security bodies covering economics, politics, security, and intelligence. This was a long anticipated document on which both Russia and Iran had been working on. The agreement was signed in Moscow by the Deputy Secretary-General of the Supreme Security Council of Iran, Ali Bagheri (Baqeri), and the Under-Secretary of the National Security Council of Russia, Yevgeny Lukyanov. In November 2011, the head of the Committee for International Affairs in the Russian Duma, Konstantin Kosachev, also announced that Russia must do everything it can to prevent an attack on neighbouring Iran. At the end of November 2011 it was announced that Dmitry Rogozin would definitely visit both Tehran and Beijing in 2012, together with a team of Russian officials to hold strategic discussions on collective strategies against common threats.

Russian National Security and Iranian National Security are Attached On January 12, 2012, Nikolai Patrushev told Interfax he feared that a major war was imminent and that Tel Aviv was pushing the U.S. to attack Iran. He dismissed the claims that Iran was secretly manufacturing nuclear weapons and said that for years the world had continuously heard that Iran would have an atomic bomb by next week ad nauseum. His comments were followed by a dire warning from Dmitry Rogozin. On January 13, 2012, Rogozin, who had been appointed deputy prime minister, declared that any attempted military intervention against Iran would be a threat to Russia’s national security. In other words, an attack on Tehran is an attack on Moscow. In 2007, Vladimir Putin essentially mentioned the same thing when he was in Tehran for a Caspian Sea summit, which resulted in George W. Bush Jr. warning that World War III could erupt over Iran. Rogozin’s statement is merely a declaration of what has been the position of Russia all along: should Iran fall, Russia would be in danger. Iran is a target of U.S. hostility not just for its vast energy reserves and natural resources, but because of major geo-strategic considerations that make it a strategic springboard against Russia and China. The roads to Moscow and Beijing also go through Tehran, just as the road to Tehran goes through Damascus, Baghdad, and Beirut. Nor does the U.S. want to merely control Iranian oil and natural gas for consumption or economic reasons. Washington wants to put a muzzle around China by controlling Chinese energy security and wants Iranian energy exports to be traded in U.S. dollars to insure the continued use of the U.S. dollar in international transactions. Moreover, Iran has been making agreements with several trade partners, including China and India, whereby business transactions will not be conducted in euros or U.S. dollars. In January 2012, both Russia and Iran replaced the U.S. dollar with their national currencies, respectively the Russian rouble and the Iranian rial, in their bilateral trade. This was an economic and financial blow to the United States.

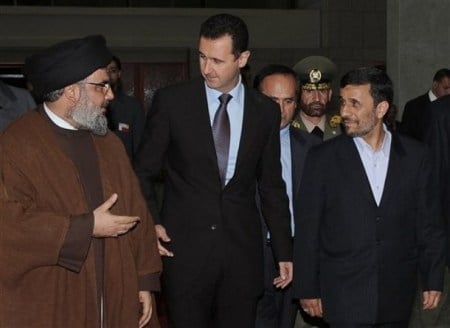

Russia and China with Iran are all staunchly supporting Syria. The diplomatic and economic siege against Syria is tied to the geo-political stakes to control Eurasia. The instability in Syria is tied to the objective of combating Iran and ultimately turning it into a U.S. partner against Russia and China. The cancelled or delayed deployment of thousands of U.S. troops to Israel for “Austere Challenge 2012” was tied to ratcheting up the pressure against Syria. On the basis of a Voice of Russia report, segments of the Russian media erroneously reported that “Austere Challenge 2012” was going to be held in the Persian Gulf, which was mistakenly picked up by news outlets in other parts of the world. This helped highlight the Iranian link at the expense of the Syrian and Lebanese links. The deployment of U.S. troops was aimed predominately at Syria as a means of isolating and combating Iran. The “cancelled” or “delayed” Israeli-U.S. missile exercises most probably envisaged preparations for missile and rocket attacks not only from Iran, but also from Syria, Lebanon, and the Palestinian Territories. Aside from its naval ports in Syria, Russia does not want to see Syria used to re-route the energy corridors in the Caspian Basin and the Mediterranean Basin. If Syria were to fall, these routes would be re-synchronized to reflect a new geo-political reality. At the expense of Iran, energy from the Persian Gulf could also be re-routed to the Mediterranean through both Lebanon and Syria.

Related Articles

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Global Research | |||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)