Two million helpless people in Gaza have nowhere to run, nowhere to hide and no way to save their children

A Palestinian child receives medical care after being hit by an Israeli air strike in Deir Al Balah, Gaza, on 14 October 2023 (Reuters)

As these lines are being written, Israel has informed the UN that more than one million people in the northern Gaza Strip, including residents of Gaza City, must evacuate their homes. There is nowhere to go in Gaza – not for 10,000 people, not for 100,000 and certainly not for a million.

To evacuate one million human beings within 24 hours is impossible, illegal, inhuman and impractical.

In other words, Israel is threatening to commit a war crime the likes of which we have not seen since the Nakba of 1948.

Very possibly, this is all talk and threats; Israel may not ultimately invade Gaza, and a million people may not be evicted. In any case, nearly half-a-million are newly homeless following unprecedented bombings of Gaza neighbourhoods by the Israeli Air Force.

These are dark days. Dark days for Israelis, who woke up last Saturday to a reality that turned upside-down their conception of their world that they had embraced for years.

Israelis believed that their army was omnipotent, the strongest in the world; that sinking 3.5 billion shekels ($1bn) into the barrier around Gaza would be sufficient to ensure the security of the residents of southern Israel.

They believed that they had the most sophisticated intelligence system in the world – one that knows, hears and sees everything. Israel is equipped with miraculous technology that it sells to half the world, and boasts elite human resources, such as the army’s celebrated Unit 8200, born geniuses who clearly could not be surprised by anyone.

Different reality

Then, the fence around Gaza was breached by an obsolete tractor, and the entire concept collapsed. It turns out, Israeli intelligence knew nothing about a huge operation that had been planned for more than a year; the army showed up very late to the sites of the Hamas incursions.

Israel is not so powerful or omnipotent after all. Its military strength is not enough to guarantee the security of its residents. What remains highly doubtful is whether Israel will learn the most essential lesson from this: that the country cannot continue forever to live only by the sword, relying solely on its military power.

Half of the Israeli army is currently guarding settlers in the occupied West Bank and all their capricious carryings-on. For the Sukkot holiday, several battalions were moved from the Gaza border to Huwwara, near Nablus, to protect a festival of revenge initiated by an extremist member of Israel’s parliament.

Media images of Jewish worshippers sitting on a road in the middle of a Palestinian town, swaying from side to side like so many ritual palm fronds, were among the most grotesque of recent times. The grotesquery soon made way for catastrophe: because of this defiantly criminal provocation by the settlers, the residents of southern Israel had no one to protect them when Hamas forces invaded.

Last Saturday, Israel woke up to a different reality – one that should finally extinguish the country’s arrogance and complacency. This ought to demonstrate, once and for all, the impossibility of evading any consequences for continuing to indefinitely imprison more than two million people in a giant cage, with another three million people living indefinitely under military tyranny.

There was a price to be paid, after all. Last Saturday, Israel woke up to horror upon horror.

Israel was shocked and sought revenge. That wish is now fulfilled. As I write this, all residents of Gaza have become potential victims of a violence that even they, however much they already know of horror and suffering, have not previously known.

Trauma of the Nakba

Thousands and perhaps tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza will not live for many more days. Their homes, their lives and their world will be completely destroyed.

Those who are forced to evacuate will certainly remember how their parents and grandparents were forced to evacuate hundreds of villages in their homeland in 1948, unable ever to return. The trauma of the Nakba will reawaken now in all its intensity, in Gaza.

What is the Nakba?

The Nakba is one of the key events in modern Middle East history and one that has come to define the Israeli-Palestinian conflict ever since.

Also known as “The Catastrophe”, it began in late 1947 and 1948, as the new state of Israel came into existence.

Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire for hundreds of years until it was captured by the UK at the end of World War One (1914-18).

The League of Nations – a forerunner of the UN – gave Britain a “mandate” over Palestine after the war, which did not take into account the wishes of the native Palestinian population.

The aim of such mandates was to bring about “the rendering of administrative assistance and advice” to native populations until they were deemed capable of standing alone as independent states.

What was the problem?

The British Mandate incorporated the Balfour Declaration, sent by Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, to Lord Walter Rothschild, a prominent member of the British Jewish community, in 1917.

It pledged to establish “in Palestine a national home for the Jewish people”, who made up less than 10 percent of the population at the time.

During the mandate years (1923-48), the UK facilitated the immigration of European Jews to Palestine, increasing their population 10-fold, from 60,000 in the pre-Mandate era to 700,000 by 1948.

They also trained, armed and supplied Zionist groups, and allowed them a degree of self-governance.

In contrast, the native Palestinian population, which rejected European Jewish immigration and called for independence, was violently suppressed.

The number of Jews arriving in Palestine from Europe and elsewhere increased in the wake of the Holocaust, which systemically targeted Jews and others, resulting in the deaths of more than 6m people.

In February 1947, Britain announced it would terminate the mandate and turn the question of Palestine over to the newly formed United Nations.

The UN adopted a partition plan in November 1947, which divided Palestine into two parts: 55 percent would form a Jewish state, while 45 percent would create an Arab state. Jerusalem would be kept under international control.

But many argue that the plan did not take into account populations at the time.

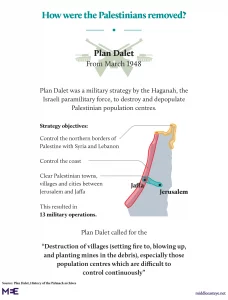

In addition, Jewish paramilitary groups produced a strategy to control the borders of the new territory, called Plan Dalet (below).

Some of their members would go on to become key Israeli leaders, including Yitzhak Rabin (prime minister 1992 – 1995), Ariel Sharon (prime minister 2001 – 2006) and Moshe Dayan (minister of defence 1967 – 1974).

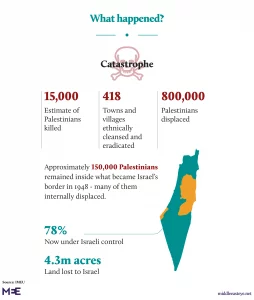

In the weeks and months that followed, thousands of Palestinians were killed or driven from their homes and communities uprooted by Jewish paramilitary groups.

Jews were also killed by Palestinian groups, if not in the same numbers.

On 14 May 1948, the State of Israel was unilaterally declared, a day before the British Mandate officially expired.

The new state had increased its share of historic Palestine from 55 percent to 78 percent. The remaining 22 percent was under Arab control.

Many of the Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes never returned to historic Palestine. Much of it is now the modern-day state of Israel.

More than 70 years later, millions of their descendants live in dozens of refugee camps in Gaza, the West Bank, and surrounding countries, including Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon.

Many still keep the keys to the homes that they and their families were forced to leave.

Nakba Day is now a key commemorative date in the Palestinian calendar. It is traditionally marked on 15 May, the date after Israeli independence was proclaimed in 1948.

Some Palestinians also observe it on the day of Israeli independence celebrations, which itself changes from year to year due to variations in the Hebrew calendar.

It must be clear that, notwithstanding the understandable, friendly human sympathy that has been expressed, Israel’s response cannot be unrestrained.

As I was writing these lines, a resident of Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip called me, asking to send an article to Haaretz, the newspaper for which I write. “I don’t know if I’ll still be alive in a few hours,” he said. “Right now, no one in Gaza knows if they will be alive in another hour – but please publish the article even if I am killed.”

At some stage, these atrocities will have to be stopped – and that stage is very close.

Gideon Levy is a Haaretz columnist and a member of the newspaper’s editorial board. Levy joined Haaretz in 1982, and spent four years as the newspaper’s deputy editor. He was the recipient of the Euro-Med Journalist Prize for 2008; the Leipzig Freedom Prize in 2001; the Israeli Journalists’ Union Prize in 1997; and The Association of Human Rights in Israel Award for 1996. His new book, The Punishment of Gaza, has just been published by Verso.

This article was originally published by Middle East Eye

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.com