Just after dawn on March 16, 1968, a company of U.S. Army infantrymen, led by Capt. Ernest Medina and spearheaded by Lt. William Calley, entered the small hamlet of My Lai in Quang Ngai province, South Vietnam.

The villagers, mostly women and children, had no idea what was coming that day.

If they had, they’d have fled.

Despite facing zero resistance and finding only a few weapons, Calley ordered his men to execute the entire population.

In all, some 500 Vietnamese civilians were executed, including more than 350 women, children and babies.

Other senior leaders in the chain of command had advised the soldiers of Charlie Company that all people in the village should be considered either Viet Cong or VC supporters. Medina and Calley were ordered to destroy the village. They did so with brutal precision and savagery.

The Army covered up the massacre for more than a year, until journalist Seymour Hersh broke the story in November 1969.

Now obliged to conduct a public investigation into what was no doubt a major war crime, the Army’s investigating officer recommended that no fewer than 28 officers be charged in the killings and subsequent cover-up.

Medina, Calley and most other participants in the slaughter chose to plead—just as Nazi soldiers had—that they were only following orders.

That may well have been true. Still, military regulations—then and now—oblige a soldier or officer not to follow illegal or immoral orders.

Nonetheless, in subsequent trials, all but one of the defendants were acquitted by sympathetic juries. Only Calley, the ringleader, received a life sentence.

On appeal, that sentence was reduced to 20 years; later, President Richard Nixon ordered Calley transferred to house arrest at his quarters in Fort Benning, Ga., until finally, the lieutenant was paroled in 1974.

More than 500 innocent Vietnamese lives were apparently worth naught but three years and a stint of cushy house arrest for a single Army lieutenant.

No colonels or generals were held seriously accountable. This is typical; the burden of responsibility generally flows downhill, and junior leaders are left holding the proverbial bag.

A staggering 77% of Americans polled felt that Calley was scapegoated; a popular song supportive of the defendant, titled “The Battle Hymn of Lt. Calley,” was even released. It included such absurd lyrics as:

My name is William Calley, I’m a soldier of this land

I’ve tried to do my duty and to gain the upper hand

But they’ve made me out a villain, they have stamped me with a brand.

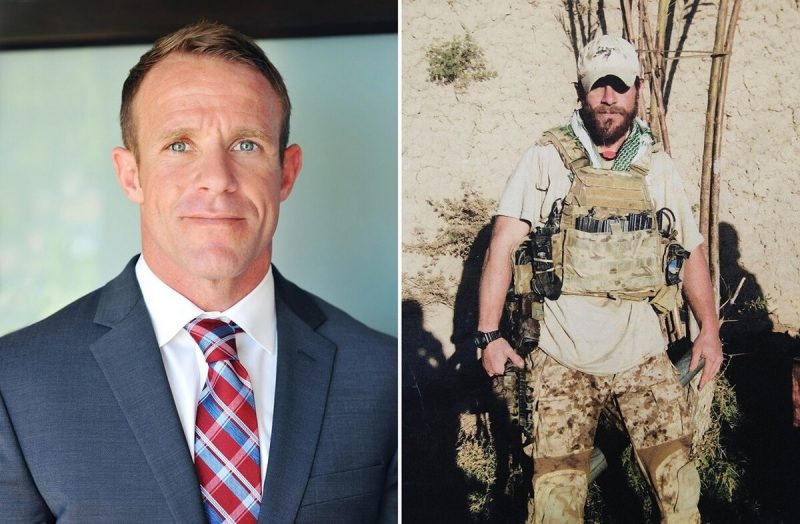

I got to thinking about this, the worst (reported) American massacre in the criminal Vietnam War, when California Rep. Duncan Hunter recently defended a Navy SEAL, Special Operations Chief Edward Gallagher, who was accused of committing murder and other horrific crimes during a 2004 tour in Afghanistan.

According to reports, President Donald Trump is considering a pardon for Gallagher and other convicted war criminals from the so-called war on terror.

This would be, to say the least, a morally reprehensible act, one likely to encourage more American servicemen to abuse their power and break internationally recognized rules of war. That the story has garnered so little attention is a tragedy of the first order.

Still, Hunter’s comments and Trump’s consideration should come as little surprise.

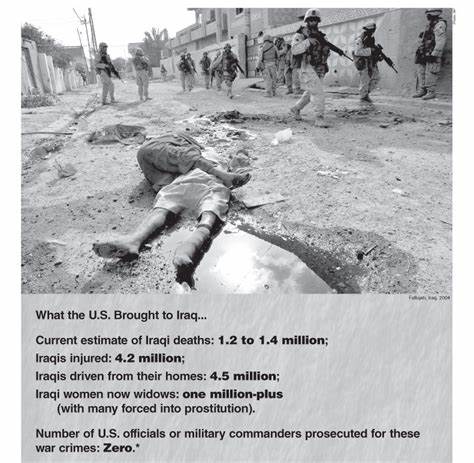

The U.S. military and the government in Washington have rarely held accused American war criminals accountable.

And with a sympathetic populace here at home—one that trusts primarily the military among public institutions—expect current and future U.S. war criminals to get a pass (or what Hunter called “a break”).

This is not only ethically repugnant, it further sullies what’s left of America’s reputation abroad and will only increase terrorist recruitment and endanger the U.S. homeland.

In the case of Gallagher, the Navy chief stands accused of shooting civilians and murdering a teenage Islamic State captive with his knife.

Afterward, Gallagher allegedly posed for photos with the corpse, texted the images to friends and even held a re-enlistment ceremony over the body.

Rep. Hunter, himself facing federal corruption charges, brushed off Gallagher’s actions, admitting that as an artillery officer in Fallujah, Iraq, he’d “killed probably hundreds of civilians” and had “[p]robably killed women and children.” Hunter wondered aloud, “So do I get judged too?” He should—but he undoubtedly won’t.

Hunter went even further, stating that “I frankly don’t care if [the captive] was killed, I just don’t care,” and adding, “Even if everything that the prosecutors say is true in this case, then, you know, Eddie Gallagher should still be given a break, I think.”

Such a despicable statement, and Hunter’s admission of his own criminal acts in Iraq, should stagger us all.

But again, it won’t have that effect. Here’s the kicker: Gallagher wasn’t railroaded by a dovish press or “liberal” legal system—his fellow SEALs turned him in.

Apparently, many American soldiers don’t agree with Gallagher, Hunter or Trump; they actually possess an independent moral compass.

War crimes of this magnitude, while rare, do occur in the “war on terror.”

In some cases, the perpetrators have been held accountable, but they’ve just as often been let off. Few were punished for rampant prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, and essentially no high-ranking military or government officials were held accountable.

Nor was any senior official charged with torture for the post-9/11 CIA practice of waterboarding—a crime for which Japanese military leaders were executed after World War II. Generals hardly ever go to jail here in the “land of the free.”

Neither—or not for long—do war criminal mercenary contractors, apparently. Trump is also reportedly considering a pardon for Blackwater employee Nick Slatten, who was twice convicted of shooting to death dozens of Baghdad civilians in 2007.

I was in that chaotic city when Slatten opened fire on a crowded square, and my unit had to deal with the consequences. Understandably, Iraqis didn’t distinguish between us soldiers and the similarly clad contractors, over whom we had no control.

To the Iraqi populace, Americans were Americans, and it is highly likely that support for the insurgency and the killing of U.S. troops increased after the Blackwater shooting and Abu Ghraib scandal. I was told as much by many Iraqis in the ensuing months.

In terms of Hunter, Trump and Gallagher, let us be clear: The logical extension of a pardon would be that there becomes essentially no such thing as an American war crime.

That would overturn everything I learned regarding the laws of war in my 18-year military career. Hunter may claim that photographing corpses was commonplace and that “a lot of us have done the exact same thing,” but that’s patently false.

Most of my fellow officers did follow the rules of war, didn’t parade enemy or civilian corpses, and did everything they could to avoid noncombatant casualties. We were ethically and legally obliged to do so.

Admittedly, the ill-advised, illegal and immoral American invasion of Iraq resulted in hundreds of thousands of civilians’ deaths—killed by all sides, including our own.

I’m not excusing that loathsome and unnecessary war; not by a long shot. I remain haunted by my own participation in the conflict and the likelihood that my unit accidentally killed civilians during various and confusing firefights.

Still, there must be some standard of conduct for America’s “warriors,” my own included. What sort of society would America be if its soldiers were free to rape, pillage and plunder in current and future wars? A venal empire, that’s what—which this country resembles more and more.

That Trump would consider pardons for Gallagher, Slatten and other accused or convicted murders also reflects the nepotism that informs his administration.

Gallagher’s defense attorney also represents the Trump organization, and Slatten’s former boss at Blackwater, Erik Prince, is the brother of Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos.

A Trump pardon, moreover, would relieve the enormous U.S. war machine of any responsibility to wage war morally or legally.

It would set a dangerous precedent, encourage other potential murderers in uniform and champion the notion that the U.S. military has the right to do as it pleases the world over.

Hunter’s reprehensible verbal nonsense and Trump’s potential pardons reflect a military chauvinism that infuses the American vernacular in the 21st century.

The dangerous doctrine of American exceptionalism applies, apparently, to this country’s so-called exceptional right to commit war crimes with impunity.

Thinking back to My Lai, though, it seems that whitewashing, excusing and apologizing for criminal military behavior is as American as apple pie. Hunter and Trump just say as much out loud.

Maj. Danny Sjursen is a retired U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan.

This article was originally published by “TruthDig“-

The 21st Century