There is a hidden war being waged against Yemen, a multinational assault against the country’s vital natural resources. For years, foreign states and companies have engaged in the illicit plundering of Yemen’s oil and gas – war profiteering in the poorest nation in West Asia.

The US-backed and Saudi-led war in Yemen has not only created a severe countrywide humanitarian crisis, but has also spawned external competition over the looting of Yemen’s natural resources, particularly oil and gas. Yemen’s strategic location and its many ports make it an ideal hub for transporting stolen resources quickly and efficiently.

While the eight-year conflict has somewhat subsided due to ongoing direct peace talks between Riyadh and Sanaa, the exploitation of these resources continues unabated, with different Yemeni authorities and external states vying for control.

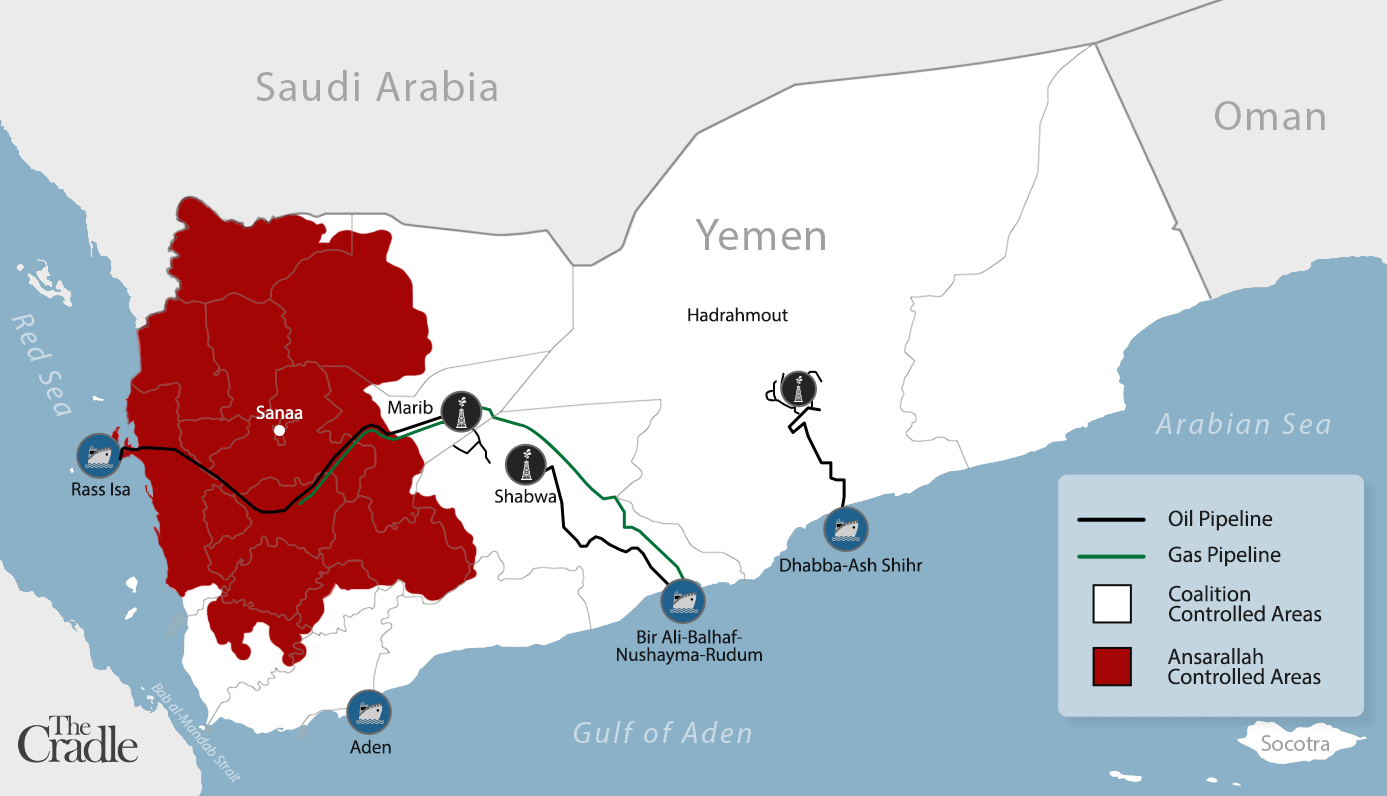

Three active oil and gas fields are currently under the authority of foreign aggressors who lead the war coalition in Yemen. Marib, a resource-rich region, produces both oil and gas and is controlled by the Saudi-backed internationally-recognized government.

The southern province of Shabwa, with its oil wells and pipeline, is under the control of the UAE-supported Southern Transitional Council (STC).

The southern province of Hadhramaut, also known for its oil reserves, is technically governed by the internationally-recognized government, while its ports are under the authority of the STC.

The latter has since stepped up its separatist ambitions setting its sights on the resource-rich province, in a development likely to cause a conflict of interests and proxies with coalition partner Saudi Arabia.

The forced closure of pipelines that connect Ansarallah-controlled areas to other provinces has cut off Sanaa’s access to oil and gas resources, resulting in immense suffering for the majority of Yemeni citizens, as most of them reside in these areas.

A geoeconomic motive for the war?

In March 2015, the war on Yemen was initiated by a coalition led by Saudi Arabia in support of the government of Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, who had been ousted by resistance movement Ansarallah and their allied military forces in the “September 21 Revolution” during Yemen’s 2014 uprising, inspired by the so-called Arab Spring.

Eight years later, Hadi’s government no longer exists, and the 77-year-old himself was forced into retirement in April 2022 by his Saudi sponsors. In his place, an unelected “Presidential Leadership Council” (PLC) has assumed executive powers, in accordance with directions from Riyadh.

The ongoing conflict has caused direct and indirect losses of over $45 billion to Yemen’s oil sector. Meanwhile, the war coalition continues to sell millions of barrels of oil through Yemeni ports on a regular basis.

That the war in Yemen has sparked a geopolitical struggle for control and appropriation of natural resources has often been overlooked in the mainstream foreign media – despite being an integral part of the devastating conflict – and mirrors similar violations seen in other parts of West Asia, most notably in Syria where US military troops oversee the daily looting of Syrian oil and agricultural resources.

Competing Yemeni authorities

Amidst recent negotiations between Riyadh and Sanaa, spurred by the diplomatic rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, the intensity of the war in Yemen has subsided.

However, the war’s original objectives have become increasingly muddied as various coalition partners pursue wildly diverging agendas. As the “short” war turned into months and then years, many of them have also sought to plough Yemen’s riches to fill their emptying coffers.

Today, the coalition is primarily composed of lead partners Saudi Arabia and the UAE, with the US and UK providing arms, intelligence, and logistical support from the shadows.

To further their own interests, each coalition member has established and armed their own version of a Yemeni government – Saudi Arabia created the PLC (“internationally-recognized government”), while the UAE formed the STC in the south of the country.

The PLC, STC, and their affiliated factions exert control over the resource-rich provinces, as well as nearly all of Yemen’s major ports and waterways. In contrast, Ansarallah exercises control over the central government in the capital Sanaa, as well as the other densely-populated regions in the surrounding northern provinces.

Control and exploitation of resources

As previously mentioned, Yemen possesses three operational oil and gas fields. The Marib field, for instance, features an oil pipeline that extends into regions controlled by Ansarallah, ultimately reaching the western coast of Yemen on the Red Sea at Ras Isa port.

Regarding its gas reserves, Marib has two main destinations: one pipeline extends south of Sanaa, reaching Dahmar, while the other pipeline stretches all the way to the Gulf of Aden, specifically to Balhaf Port.

Marib is currently controlled by the Saudi-backed PLC, led by Rashad al-Alimi, and governed by Sultan al-Aradah. It is the “internationally-recognized” government’s last remaining northern stronghold in Yemen.

Second, there is the southern province of Shabwa, which boasts several oil wells and a pipeline that reaches the Gulf of Aden (Bir Ali Port). Shabwa has been under full control of the UAE-backed STC since 2022.

Last but not least is the Yemeni province of Hadhramaut, known for its multiple oil wells and a pipeline that also extends to the Gulf of Aden (Dabba Port). Hadhramaut is governed by the PLC, while its ports are under the authority of the STC.

Yemen’s struggling oil sector

Oil and gas are vitally important for the Sanaa government, not only for their use in domestic energy consumption but also for paying the salaries of Yemen’s civil servants. As Essam Al-Mutawakel, spokesperson for the Sanaa-based Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC), highlighted in a tweet in March:

“The economy of Yemen depends mainly on oil & gas revenues that are under the control of the countries of the US-Saudi coalition, which constitutes 70 percent to 80 percent of the state budget and revenues. Salaries were paid from those revenues.”

However, following the launch of the coalition’s war on Yemen, a primary objective became the forced closure of pipelines that connected Ansarallah-controlled areas to other provinces, effectively cutting off Sanaa’s access to the country’s oil and gas resources, along with the associated revenues.

Consequently, this has led to immense suffering for millions of Yemeni citizens, especially considering that approximately 80 percent of the population resides in regions under Ansarallah’s control.

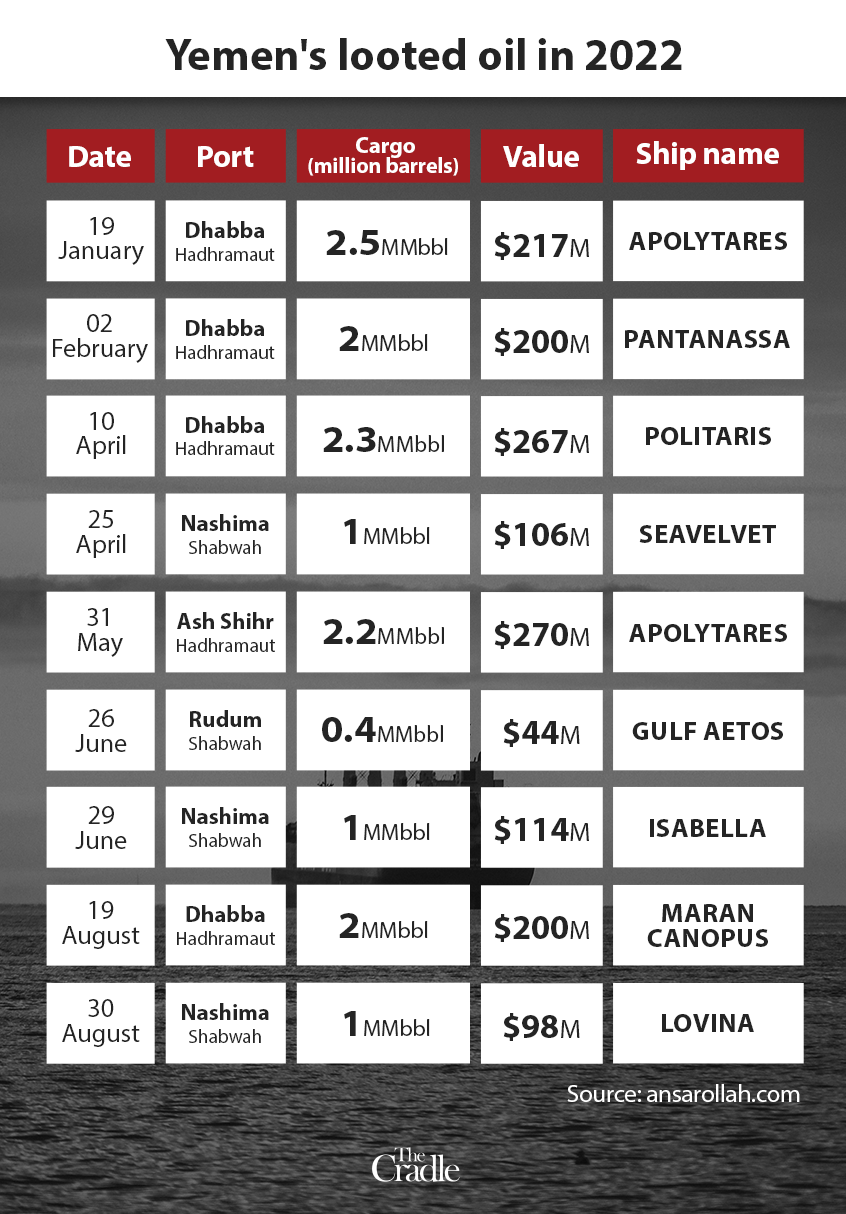

Last October, detailed information on tankers that participated in the looting process was released by Ansarallah. The chart below breaks down the amounts of oil stolen during 2022, and by which foreign-owned vessels:

Tracking Yemen’s stolen oil

While Yemen’s oil is liberally being transported overseas, most of the country’s own population is barred from accessing their own resources. Reports from the PLC indicate that Yemen’s oil exports surged from 6.672 million barrels annually in 2016 to 25.441 million in 2021.

The question remains: where does the oil and gas go, how does it get there, and who benefits from these revenues?

Tracking the various tankers engaged in oil and gas looting off the shores of Yemen is a challenging task. These tankers often take complex routes and deliberately switch off their GPS and tracking systems to conceal the origin of their cargo.

In March, the Ekad platform released an investigative video detailing the theft of Yemen’s oil. The focal point of the investigation was a tanker named ‘Gulf Aetos’ – a vessel named by Ansarallah in multiple documents.

The investigation begins with the tanker docking at Khor Fakkan Port in the UAE. On 25 June, the Gulf Aetos set sail from the Emirates and headed toward Bir Ali port in southern Yemen. There, it was loaded with oil before heading to Aden Port, where the oil was unloaded.

For a period of 30 days, the ship repeated the same specific, peculiar routine—loading from Bir Ali port and unloading in Aden port. Although the exact nature of these maneuvers remains undisclosed, it is speculated that they could be related to maritime security or the redistribution of the oil.

On 5 August, the ship returned to the UAE and docked off the shores of Fujairah, but its task was not yet complete.

Later another tanker named Star Z approached Gulf Aetos. The two ships mixed their crude oil either to make their shipments untraceable or to enhance the quality of the oil. Mixing heavy and light oil can result in a superior product.

However, in this instance, it is highly likely that the mixing was done to obfuscate the oil’s origin. Following the oil mixing, Gulf Aetos continued its journey to Khor Al Zubair port in Iraq, where the oil was unloaded.

According to Ekad’s investigation, the Iraqi port is renowned as the international hub for the redistribution of smuggled oil. The investigation noted that Singapore and the US are among the main destinations of the smuggled oil exported from this port.

Western complicity

Not too dissimilar from the case of Syria, the theft of Yemen’s resources has been made possible with the approval and supervision of the US and its allies, implicating their role in the ongoing exploitation.

For decades, the US has acted as a maritime security guarantor for the Persian Gulf monarchies, with its Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) alliance stationed in West Asian waters since 1983. The CMF’s responsibility covers the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, and the Gulf of Aden – precisely where the looting of Yemen’s resources occurs.

Interestingly, while the US has intercepted and seized ships in these waters in recent years, none of them were the tankers engaged in oil theft from Yemen. This raises suspicions over the motives behind such selective actions.

Similar patterns can be observed with the presence of British and French soldiers strategically placed in oil-rich regions like Hadhramaut. Though their numbers may be small, reports suggest that their purpose is to ensure the “security” of the oil-exporting process.

This mirrors tactics employed by the US military in Syria, where a limited number of troops were deployed to oversee the ongoing oil theft in the country’s northeast.

Numerous foreign companies also profit from this theft. One prominent name that repeatedly surfaces is the French oil and gas giant TotalEnergies. The firm has a track record of human rights violations in Yemen and the exploitation of its resources.

A detailed report from SABA, the official news agency of Sanaa’s government, reveals that in March 2022, the UAE and TotalEnergies agreed to resume gas exports through the Balhaf gas terminal in the Gulf of Aden.

Shockingly, the document exposes how the Americans and the French proposed selling the gas at a mere $3 per million BTUs, significantly below the global price of around $15, due to the Ukraine-Russia conflict.

These deals expose the exploitation of Yemen’s resources, with the UAE signing off on agreements over territories well outside of its jurisdiction, while the west plays its part in facilitating the process.

Notably, the coalition’s looting extends beyond oil and gas revenues; it also encompasses the confiscation of customs tariffs and fees from all transiting aircraft, vehicles, and ships, further adding to the plunder.

Selective outrage from the west

Despite the devastating war inflicted upon Yemen and its people, the condemnation from the west has been unsurprisingly minimal. In the past six years, only a single condemnation was issued when the Ansarallah-aligned armed forces targeted the port of Al-Dabba twice with drones in October 2022.

Both the US and the EU strongly criticized the attacks, despite there being no human casualties or injuries. In contrast, the Yemeni war has resulted in the loss of over 377,000 lives, with 70 percent of the victims being children under the age of five, as reported by the UN.

Prior to the drone strikes, Ansarallah had issued warnings, vowing to retaliate against the systematic oil theft taking place in the southern part of the country.

After the attack, the spokesperson of the Yemeni Armed Forces, Yahya Saree tweeted:

“Our armed forces carried out a simple warning strike, in order to prevent an oil ship that was trying to loot crude oil through the Dabba port in Hadramout Governorate.”

Local sources from Hadhramaut confirm to The Cradle that following the attacks, the oil theft declined but did not cease.

According to Ekad and Ansarallah, the majority of ships involved in smuggling oil from Yemen fly the flag of Panama, a small Latin American country with a disproportionately large number of vessels registered under its flag. Importantly, many of these ships are owned by UAE-based companies, as well as Greek and Chinese firms.

Gulf Aetos, for example, is owned by Blue Pearl Shipping and Trading and is managed by Gulf of Aden Shipping – both Emirati companies.

Saudi Arabia and UAE share smuggled oil profits

The revenue from the smuggled oil is divided between coalition partners Saudi Arabia and the UAE, with the latter holding a larger share. This is due to the UAE’s control over 12 Yemeni ports spanning from the east to the west of the country, effectively giving Abu Dhabi control over the export and distribution of oil and gas.

The smuggling of Yemen’s oil and gas serves two primary objectives: First, it provides fuel for the ongoing conflict and funds the salaries for the newly established governments and their militias, whether these are Saudi or UAE-backed.

The second objective is to deprive the central government in Sanaa from benefiting from Yemen’s oil and gas resources. As in Syria, this is aimed at reinforcing the effectiveness of the siege and sanctions imposed on Yemen, and preventing revenues from reaching the de facto authorities.

In the case of the UAE, a significant portion of the revenue is allocated to politicians affiliated with the STC, most of whom enjoy luxurious lifestyles while regular Yemenis wither under enforced food and resource shortages.

These revenues also support some 200,000 well-equipped and armed STC militiamen, which one Emirati official described as Abu Dhabi’s “biggest accomplishment.”

On the other hand, the revenue collected by the PLC is directly transferred to their patrons in Saudi Arabia. In an interview, Marib Governor Sultan al-Aradah acknowledged that the money generated from oil and gas in his province goes straight to the Saudi National Bank (Al-Ahli Bank).

How do Yemenis obtain oil?

Meanwhile, the Sanaa-based government has been left with humiliating options by which to obtain vital fuel: Yemenis are forced to purchase Yemeni oil through intermediaries or private companies in UAE markets and make payments through Emirati banks.

The oil is then examined by a French company to determine its source. The ship carrying the oil undergoes inspections in Djibouti by the “UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen” (UNVIM), and finally, it sails to Jizan, Saudi Arabia, for examination by Saudi authorities.

These arbitrary procedures – amidst Yemen’s urgent need for vital energy resources – lead to prolonged delays, exacerbating the humanitarian catastrophe and causing immense suffering for Yemen’s population, as well as financial and logistical setbacks for the government.

Overcoming the legacy of looting

The looting of Yemen’s resources is expected to cease once the war ends, but the circumstances under which this will unfold remain uncertain. Recent geopolitical moves and agreements struck by Saudi Arabia suggest a Eurasian pivot in Riyadh, which essentially allows for a foreign policy less servile to Washington.

By defying requests from the Biden administration to increase oil exports, and restoring relations with US-foes Iran and Syria, Riyadh is repositioning itself on the global stage by resolving long-standing disputes and tensions with its neighbors, which were primarily ignited by western interests rather than genuine threats.

If this trend continues, Saudi Arabia may reach a bilateral agreement with Ansarallah, thus ending one important driver of the Yemeni conflict. The question remains whether Sanaa and Riyadh are prepared to strike a peace deal without the UAE, and whether the latter’s STC proxy is prepared to face the formidable northern Yemeni armed forces on its own.

Alternatively, if negotiations fail, the conflict may return to square one, as Sanaa’s Defense Minister, Mohammed al-Atifi warned in May. With no viable resolution currently on the table, Ansarallah leader Abdel Malik al-Houthi recently threatened military action against any attempts to plunder Yemen’s resources – not only its oil and gas resources, but also other valuable commodities such as metals.

The poorest country in West Asia has always had the resources to potentially be among its wealthiest. Yemen’s possibilities are vast, and the Saudis have worked assiduously to prevent this realization since the kingdom’s establishment. But the region is changing fast with the emergence of a multipolar world, and the new order favors economic development and peace over wars and sanctions.

As the agendas of Saudi Arabia, UAE, US, and UK diverge, and their global influence weakens, sustaining the war in Yemen becomes increasingly challenging.

Moreover, they face mounting pressure from China, Russia, and Iran, who seek to establish a regional security infrastructure in West Asia based on international law rather than US sanctions regimes. These dynamics indicate that the next few years are likely to bring significant changes to Yemen’s fortunes, whether the coalition likes it or not.

By Karim Shami

Published by The Cradle

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.com