The Middle East is the key to wide-ranging, economic, interlinked integration, and peace

Under the cascading roar of the 24/7 news cycle cum Twitter eruptions, it’s easy for most of the West, especially the US, to forget the basics about the interaction of Eurasia with its western peninsula, Europe.

Asia and Europe have been trading goods and ideas since at least 3,500 BC. Historically, the flux may have suffered some occasional bumps – for instance, with the irruption of 5th-century nomad horsemen in the Eurasian plains. But it was essentially steady up to the end of the 15th century. We can essentially describe it as a millennium-old axis – from Greece to Persia, from the Roman empire to China.

A land route with myriad ramifications, through Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran and Turkey, linking India and China to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea, ended up coalescing into what we came to know as the Ancient Silk Roads.

By the 7th century, land routes and sea trade routes were in direct competition. And the Iranian plateau always played a key role in this process.

The Iranian plateau historically includes Afghanistan and parts of Central Asia linking it to Xinjiang to the east, and to the west all the way to Anatolia. The Persian empire was all about land trade – the key node between India and China and the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Persians engaged the Phoenicians in the Syrian coastline as their partners to manage sea trade in the Mediterranean. Enterprising people in Tyre established Carthage as a node between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean.

Because of the partnership with the Phoenicians, the Persians would inevitably be antagonized by the Greeks – a sea trading power.

When the Chinese, promoting the New Silk Roads, emphasize “people to people exchange” as one of its main traits, they mean the millenary Euro-Asia dialogue. History may even have aborted two massive, direct encounters.

The first was after Alexander The Great defeated Darius III of Persia. But then Alexander’s Seleucid successors had to fight the rising power in Central Asia: the Parthians – who ended up taking over Persia and Mesopotamia and made the Euphrates the limes between them and the Seleucids.

The second encounter was when emperor Trajan, in 116 AD, after defeating the Parthians, reached the Persian Gulf. But Hadrian backed off – so history did not register what would have been a direct encounter between Rome, via Persia, with India and China, or the Mediterranean meeting with the Pacific.

Mongol globalization

The last western stretch of the Ancient Silk Roads was, in fact, a Maritime Silk Road. From the Black Sea to the Nile delta, we had a string of pearls in the form of Italian city/emporia, a mix of end journey for caravans and naval bases, which then moved Asian products to Italian ports.

Commercial centers between Constantinople and Crimea configured another Silk Road branch through Russia all the way to Novgorod, which was very close culturally to the Byzantine world.

From Novgorod, merchants from Hamburg and other cities of the Hanseatic League distributed Asian products to markets in the Baltics, northern Europe and all the way to England – in parallel to the southern routes followed by the maritime Italian republics.

Between the Mediterranean and China, the Ancient Silk Roads were of course mostly overland. But there were a few maritime routes as well. The major civilization poles involved were peasant and artisanal, not maritime. Up to the 15th century, no one was really thinking about turbulent, interminable oceanic navigation.

The main players were China and India in Asia, and Italy and Germany in Europe. Germany was the prime consumer of goods imported by the Italians. That explains, in a nutshell, the structural marriage of the Holy Roman Empire.

At the geographic heart of the Ancient Silk Roads, we had deserts and the vast steppes, trespassed by sparse tribes of shepherds and nomad hunters. All across those vast lands north of the Himalayas, the Silk Road network served mostly the four main players. One can imagine how the emergence of a huge political power uniting all those nomads would be in fact the main beneficiary of Silk Road trade.

Well, that actually happened. Things started to change when the nomad shepherds of Central-South Asia started to have their tribes regimented as horseback archers by politico-military leaders such as Genghis Khan.

Welcome to the Mongol globalization. That was actually the fourth globalization in history, after the Syrian, the Persian and the Arab. Under the Mongolian Ilkhanate, the Iranian plateau – once again playing a major role – linked China to the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia in the Mediterranean.

The Mongols didn’t go for a Silk Road monopoly. On the contrary: during Kublai Khan – and Marco Polo’s travels – the Silk Road was free and open. The Mongols only wanted caravans to pay a toll.

With the Turks, it was a completely different story. They consolidated Turkestan, from Central Asia to northwest China. The only reason Tamerlan did not annex India is that he died beforehand. But even the Turks did not want to shut down the Silk Road. They wanted to control it.

Venice lost its last direct Silk Road access in 1461, with the fall of Trebizond, which was still clinging to the Byzantine empire. With the Silk Road closed to the Europeans, the Turks – with an empire ranging from Central-South Asia to the Mediterranean – were convinced they now controlled trade between Europe and Asia.

Not so fast. Because that was when European kingdoms facing the Atlantic came up with the ultimate Plan B: a new maritime road to India.

And the rest – North Atlantic hegemony – is history.

Enlightened arrogance

The Enlightenment could not possibly box Asia inside its own rigid geometries. Europe ceased to understand Asia, proclaimed it was some sort of proteiform historical detritus and turned its undivided attention to “virgin,” or “promised” lands elsewhere on the planet.

We all know how England, from the 18th century onwards, took control of the entire trans-oceanic routes and turned North Atlantic supremacy into a lone superpower game – till the mantle was usurped by the US.

Yet all the time there has been counter-pressure from the Eurasian Heartland powers. That’s the stuff of international relations for the past two centuries – peaking in the young 21st century into what could be simplified as The Revenge of the Heartland against Sea Power. But still, that does not tell the whole story.

Rationalist hegemony in Europe progressively led to an incapacity to understand diversity – or The Other, as in Asia. Real Euro-Asia dialogue – the de facto true engine of history – had been dwindling for most of the past two centuries.

Europe owes its DNA not only to much-hailed Athens and Rome – but to Byzantium as well. But for too long not only the East but also the European East, heir to Byzantium, became incomprehensible, quasi incommunicado with Western Europe, or submerged by pathetic clichés.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as in the Chinese-led New Silk Roads, are a historical game-changer in infinite ways.

Slowly and surely, we are evolving towards the configuration of an economically interlinked group of top Eurasian land powers, from Shanghai to the Ruhr valley, profiting in a coordinated manner from the huge technological know-how of Germany and China and the enormous energy resources of Russia.

The Raging 2020s may signify the historical juncture when this bloc surpasses the current, hegemonic Atlanticist bloc.

Now compare it with the prime US strategic objective at all times, for decades: to establish, via myriad forms of divide and rule, that relations between Germany, Russia and China must be the worst possible.

No wonder strategic fear was glaringly visible at the NATO summit in London last month, which called for ratcheting up pressure on Russia-China. Call it the late Zbigniew “Grand Chessboard” Brzezinski’s ultimate, recurrent nightmare.

Germany soon will have a larger than life decision to make. It’s like this was a renewal – in way more dramatic terms – of the Atlanticist vs Ostpolitik debate. German business knows that the only way for a sovereign Germany to consolidate its role as a global export powerhouse is to become a close business partner of Eurasia.

In parallel, Moscow and Beijing have come to the conclusion that the US trans-oceanic strategic ring can only be broken through the actions of a concerted block: BRI, Eurasia Economic Union (EAEU), Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), BRICS+ and the BRICS’ New Development Bank (NDB), the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

Middle East pacifier

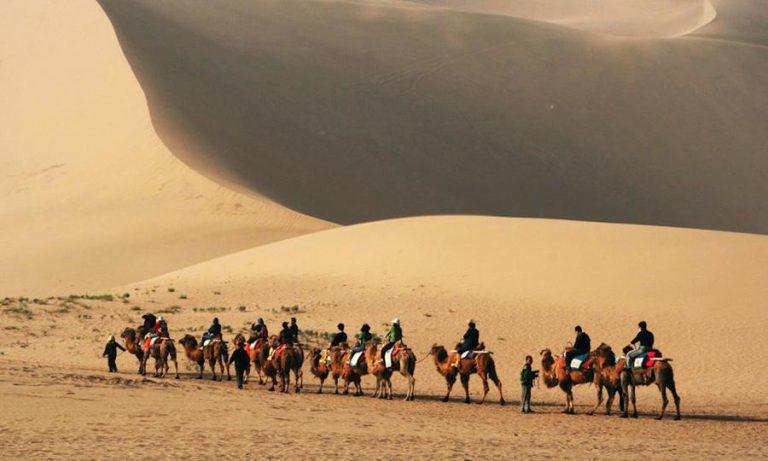

The Ancient Silk Road was not a single camel caravan route but an inter-communicating maze. Since the mid-1990s I’ve had the privilege to travel almost every important stretch – and then, one day, you see the complete puzzle. The New Silk Roads, if they fulfill their potential, pledge to do the same.

Maritime trade may be eventually imposed – or controlled – by a global naval superpower. But overland trade can only prosper in peace. Thus the New Silk Roads potential as The Great Pacifier in Southwest Asia – what the Western-centric view calls the Middle East.

The Middle East (remember Palmyra) was always a key hub of the Ancient Silk Roads, the great overland axis of Euro-Asia trade going all the way to the Mediterranean.

For centuries, a quartet of regional powers – Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and Persia (now Iran) – have been fighting for hegemony over the whole area from the Nile delta to the Persian Gulf. More recently, it has been a case of external hegemony: Ottoman Turk, British and American.

So delicate, so fragile, so immensely rich in culture, no other region in the world has been, continually, since the dawn of history, an absolutely key zone. Of course, the Middle East was also a crisis zone even before oil was found (the Babylonians, by the way, already knew about it).

The Middle East is a key stop in the 21st century, trans-oceanic supply chain routes – thus its geopolitical importance for the current superpower, among other geoeconomic, energy-related reasons.

But its best and brightest know the Middle East does not need to remain a center of war, or intimations of war, which, incidentally, affect three of those historical, regional powers of the quartet (Syria, Iraq and Iran).

What the New Silk Roads are proposing is wide-ranging, economic, interlinked integration from East Asia, through Central Asia, to Iran, Iraq and Syria all the way to the Eastern Mediterranean. Just like the Ancient Silk Roads. No wonder vested War Party interests are so uncomfortable with this real peace “threat.”

Pepe Escobar is correspondent-at-large at Asia Times. His latest book is 2030. Follow him on Facebook.

The 21st Century